Overview

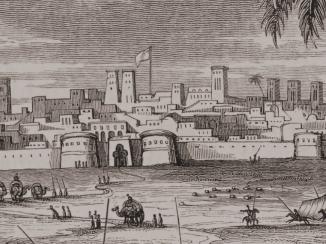

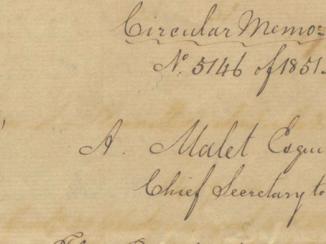

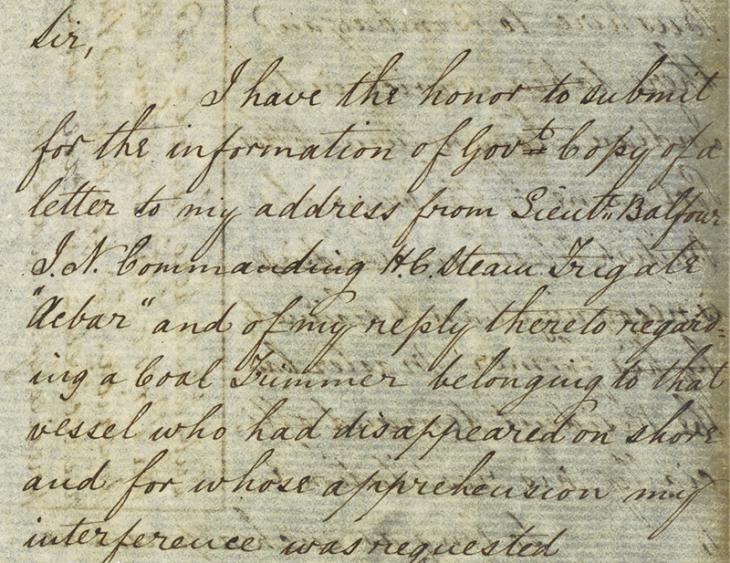

On 28 March 1854, Britain’s Resident in the Gulf, Captain Arnold Kemball, wrote to the Government of Bombay From c. 1668-1858, the East India Company’s administration in the city of Bombay [Mumbai] and western India. From 1858-1947, a subdivision of the British Raj. It was responsible for British relations with the Gulf and Red Sea regions. , reporting that a coal shoveller on the East India Company’s steam frigate Akbar, moored at the Persian port of Bushire, had deserted his post. Kemball explained that the man was a runaway slave who had formerly lived in Bushire.

Initially assumed to have been re-enslaved by his master, later reports confirmed that the man had in fact returned to his wife and child, whom he had been compelled to leave behind in his search for freedom. Kemball requested guidance from the Government. Could he allow the man to be re-enslaved by his old master in Bushire? Or did the man remain under British protection?

The Crew of the Akbar

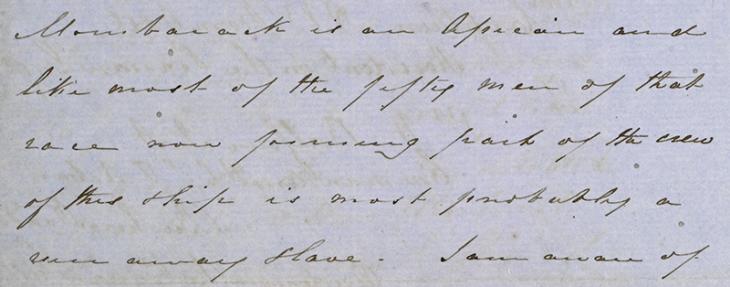

The case of the coal shoveller on the Akbar was not unique to Indian naval vessels. Slaves and manumitted slaves frequently made up the bulk of the crews employed on these ships. In his reply to Kemball’s query, the Governor at Bombay said that, according to the Akbar’s own commander, Lieutenant Balfour, European sailors in his crew numbered no more than twenty-two men, while ‘Seedees’ (or ‘Sidis’: the name frequently used to describe the Africans in the Navy’s service) – most of whom were runaway slaves – numbered fifty. ‘I am assured,’ the Governor wrote ‘that the majority of our seamen on board our steamers are at this very time Africans and that the greater of their numbers are fugitive slaves’.

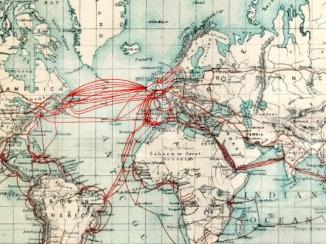

An African Diaspora

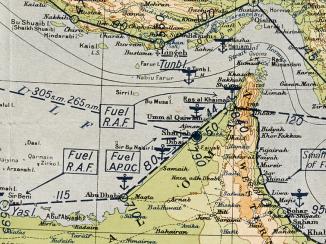

These statistics underline one aspect of the legacy of the Indian Ocean slave trade which was, arguably, at its peak during the mid-nineteenth century: itinerant men, many of whom were from East Africa, had been taken from the place of their ancestral roots and frequently shorn of their familial ties, and subsequently used Indian naval vessels as a means of absconding from their masters in order to obtain their freedom. They helped fill the ports of the Gulf and northwestern shores of the Indian Ocean with a diverse mix of peoples, including Africans, Indians, Arabs and Persians, who used them as tarrying points as they cast about for work on any vessels that passed through.

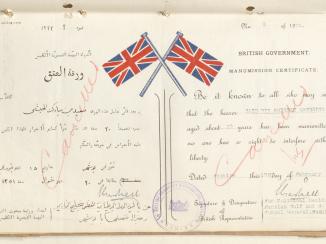

Many manumitted or runaway slaves ended up being sent by British Government officials to Bombay. Here, many were recruited into the ranks of the Indian Navy, and it is suggested that more than half of the reported two thousand Africans in Bombay in 1864 were employed in maritime work. Others were sent to agricultural plantations in places such as Zanzibar and the Seychelles, where their condition was not much better than the slavery they had escaped from.

The case of the coal shoveller on the Akbar set a precedent for future, similar cases. The Governor ruled that, if the man had deserted his vessel, as the coal shoveller on the Akbar had, then the British had no influence over the man’s fate at the hands of local authorities.