Overview

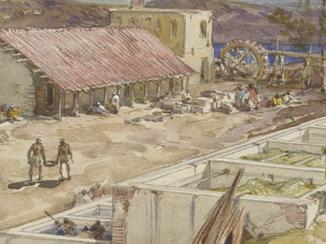

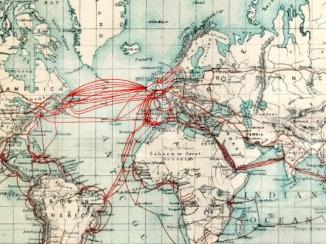

The British Empire had its seventeenth-century roots in the East India Company’s spirit of commercial enterprise and economic colonisation. By the beginning of the twentieth century the Empire’s interests had become primarily political and were focused on maintaining the economic and social status quo of its dominions to ensure its own security. This helps explain why the Gulf’s pearling industry, despite its products being expensive and highly desirable in India, Europe and North America, was preserved in its most rudimentary state, while innovations were embraced on pearl banks elsewhere in the world.

Cultured Pearls

By the early 1920s it had become evident that the Gulf’s pearling industry was in serious trouble. The drop in global demand for pearls during the First World War might have been a short-term problem, but the appearance of cultured pearls from Japan, pioneered by the entrepreneur Mikimoto Kōkichi, heralded terminal decline. The numbers of good-sized pearls being harvested from the pearl beds of the Gulf were dwindling, and simply could not complete with the abundant, cheaper products from the Far East.

Resistance to the Introduction of Cultured Pearls

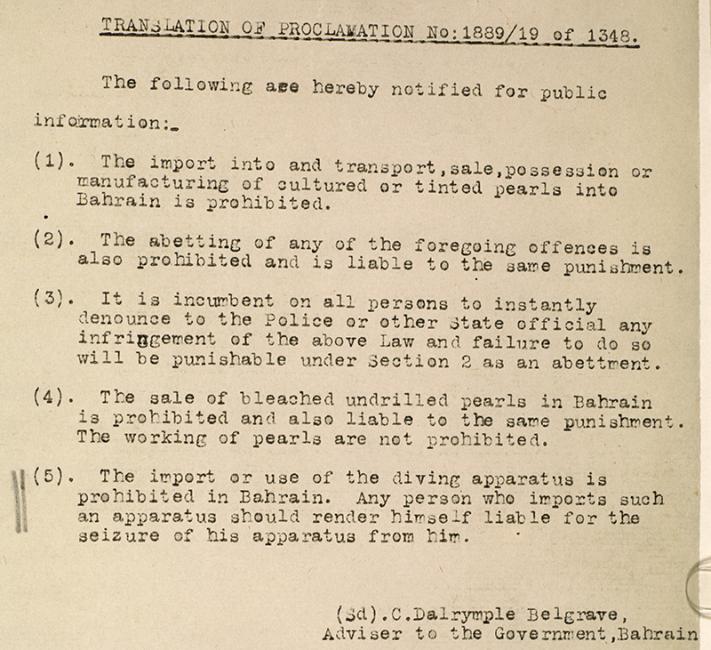

British officials in the Gulf were aware of the socio-economic problems arising from the declining pearl industry, but they were equally concerned about the potential consequences of the region embracing modern innovations such as cultured pearls.

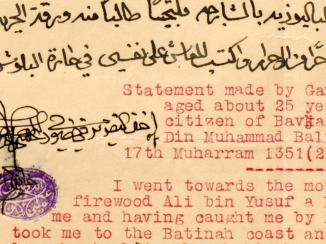

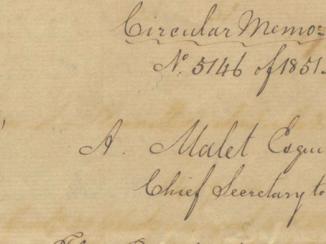

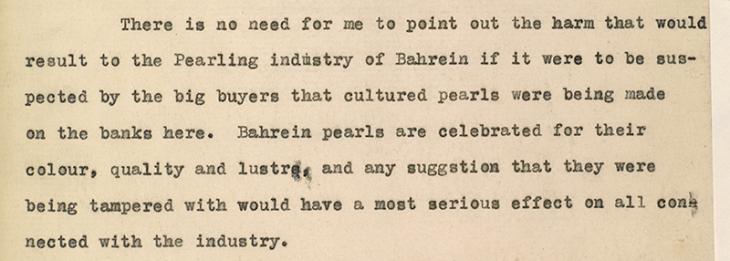

In the run-up to the 1929 pearling season, rumours emerged that a local merchant wanted to begin cultivation of cultured pearls in Bahrain. British officials were not so keen. ‘There is no need for me to point out,’ wrote Charles Prior, Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. in Bahrain at the time, ‘the harm that would result […] if it were suspected by the big buyers that cultured pearls were being made on the banks here.’ (IOR/R/15/2/122, f. 47)

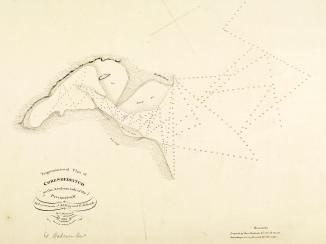

Concerns over Deep-Sea Diving Suits

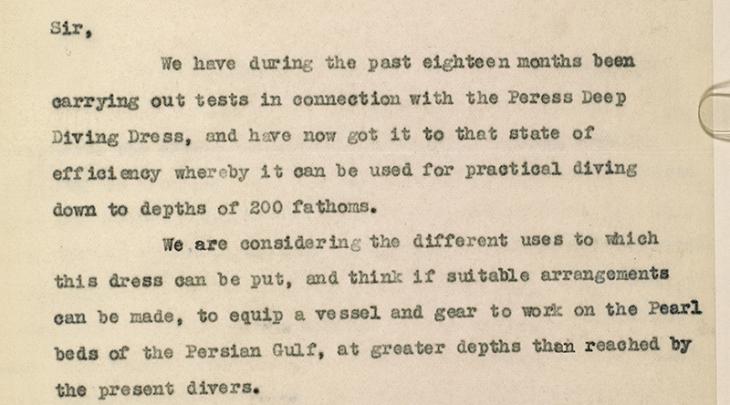

Equally concerning to the British was the possible use of modern diving aids on the pearl beds. The depths that the Gulf’s divers had hitherto been able to reach were entirely dependent on their physical capabilities, usually no more than ten fathoms. In theory, if modern diving apparatus were used, divers could reach greater depths and harvest more pearls. According to Edwin Streeter, pearl diving ‘without doubt shortens the life of those who practice it’. And yet, despite the attritional nature of diving, in a letter to Prior in Bahrain in 1930, Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. Hugh Biscoe insisted that he and his colleagues should stick to the line that ‘anyone using artificial aids to diving incurs great risks’ (IOR/R/15/1/122, f. 56).

In 1931, the Glasgow manufacturer Tritonia Limited made enquiries into the use of its deep-sea diving suit (invented by Joseph Peress) to harvest pearls in the Gulf. Their request was rejected by British Government officials who, perhaps fearful of the outcry that would ensue amongst the communities along the Arab coast, insisted that ‘the pearling banks are regarded as the common property of Arab divers’ (IOR/R/15/2/122, f. 67).

The reforms to Bahrain’s pearling industry that British officials did impose in 1924 (instigated by the then Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. Clive Daly), were limited to the regulation of the industry’s finances in a bid to prevent the worst exploitation of the divers by their boat masters. But they did not improve productivity or working conditions, and nor could they delay the inevitable collapse of the region’s pearling industry.