Overview

Prior to the start of large-scale exploitation of the region’s oil reserves in the 1950s, pearl diving was the primary economic activity along the Arabian coast of the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. . Pearls had been harvested from the waters of the Gulf from time immemorial, but it was only in the mid-nineteenth century that the industry grew quickly to meet an increasingly global demand.

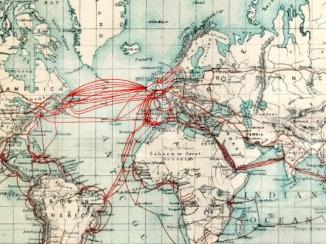

Pearls from the Gulf were traded to India, Persia and the Ottoman Empire, and further afield to Europe and North America, where the aristocratic and emerging middle classes regarded pearls as luxury items for use in jewellery and clothing. By the second half of the nineteenth century, the pearl trade in the Gulf had grown to such an extent that it united men of all backgrounds. In 1877, William Palgrave recalled how Sheikh Mohammed bin Thani of Qatar had exclaimed to him that: ‘We are all from the highest to the lowest slaves of one master, Pearl.’

Organisation of the Pearling Industry

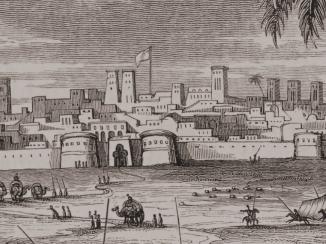

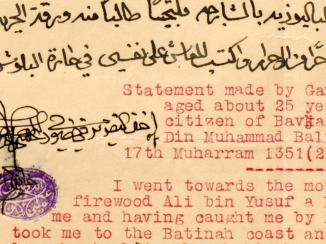

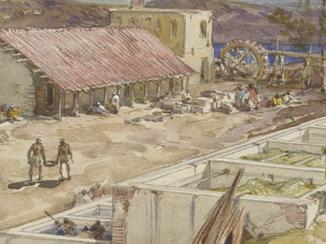

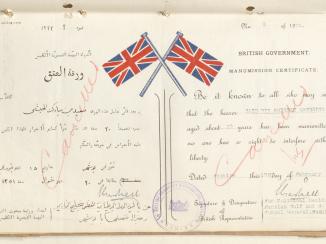

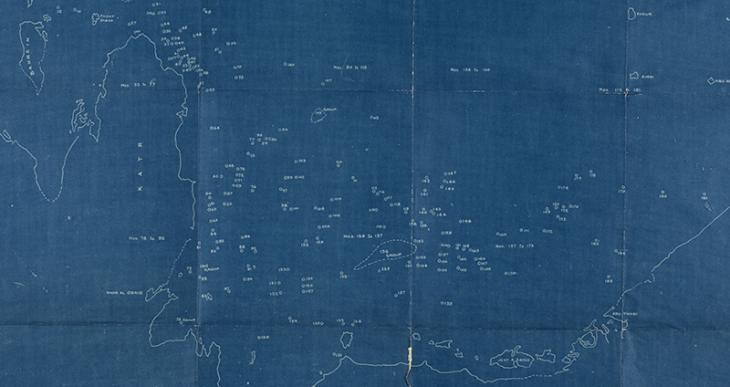

Pearl diving in the Gulf was a seasonal activity, taking place over the four months of summer. Each season, scores of pearling boats departed from ports such as Manama, Doha, Dubai and Abu Dhabi for coastal banks rich with oysters. Most of the active male populations of these towns were involved in the industry. The lowliest employees, many of whom had been enslaved in Africa and the Asian subcontinent before being transported to the Gulf, worked as divers, sailors and ‘pullers’ (those responsible for pulling the divers up by ropes from the seabed).

These men subsisted on advances given to them at the beginning of each season by their captains (nakhudas), who either owned or hired their boats and were responsible for feeding and clothing their crews. Pearl merchants (tawawish) in turn, forwarded advances to boat captains to finance the diving season. The tawawish paid the nakhudas upon the delivery of the pearls. The pearling industry therefore functioned on borrowed capital.

Historic Accounts of Pearl Diving

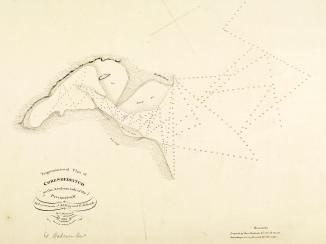

Historical sources give us some idea of the extent of pearl diving activities and the profits made over time, although the accuracy of their figures cannot be precisely verified. James Buckingham reported in his 1829 book Travels in Assyria, Media and Persia that the industry at Bahrain brought in twenty lakhs One lakh is equal to one hundred thousand rupees of rupees Indian silver coin also widely used in the Persian Gulf. annually, approximately £200,000 at the time. In his 1838 book Travels in Arabia, James Wellsted estimated that there were 3500 boats of all shapes and sizes at Bahrain at the height of the season, and a further 700 on the coast between Qatar and Oman.

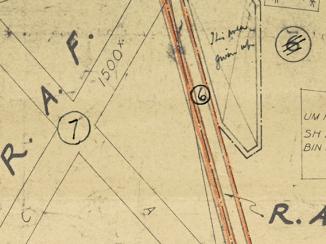

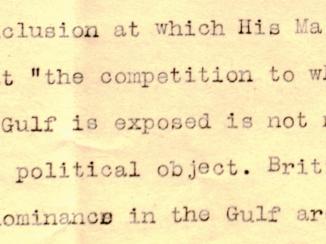

The Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. Lewis Pelly wrote a report on the pearling industry in 1865, in which he stated that there were 1500 pearling boats active in Bahrain during the pearling season, yielding a profit of £400,000 each year.

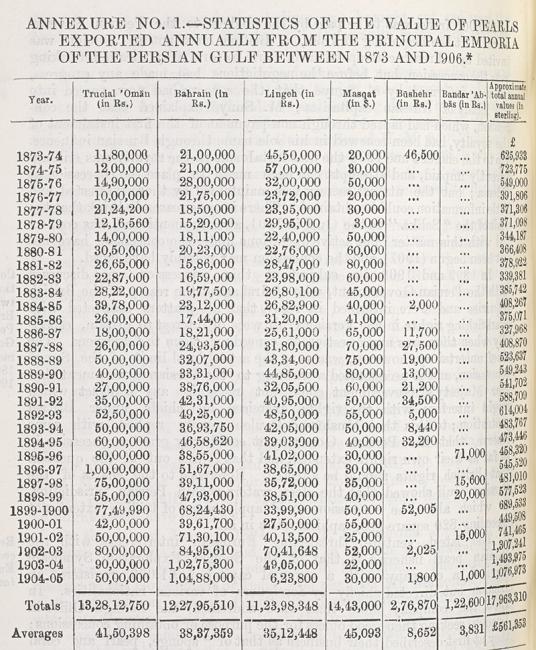

Another Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. , John Lorimer, wrote an historical account of the Gulf’s pearling industry for his Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. . He stated that the industry was worth £625,933 in 1873/74 and £1,076,793 thirty years later in 1904/05. Lorimer also reported that the Bahrain pearl fisheries employed 917 boats and over 17,500 men in 1905. At Dubai, Lorimer counted 335 pearl boats, 410 at Abu Dhabi and 350 at Doha. Paul Harrison wrote in 1924 that in the 1913 season, the value of pearls sold from Bahrain amounted to approximately nine million US dollars.

Decline

By the time Harrison visited the Gulf, the region’s pearling industry was already falling into slow decline. A major factor affecting that decline was the development of the cultured (artificially produced) pearl industry in Japan from 1916, by the entrepreneur Mikimoto Kōkichi. Cultured pearls were more abundant and up to a tenth of the price than those harvested in the Gulf.

From the 1920s, the pearl fishing fleets belonging to the towns along the Arab coast shrank, and the populations of many towns dwindled dramatically as people moved away to seek work elsewhere. Between 1908 and 1941, the population of Bahrain fell from around 100,000 to 90,000 persons (Lorimer, 1908: vol. 2; Bahrain 1941 census statistics) while Doha’s population dropped from 27,000 to 16,000 inhabitants during the 1930s.

By the early 1950s, as large-scale oil production facilities grew up across the region, the traditional pearling industry had all but disappeared from the coastal waters of the Gulf.