Overview

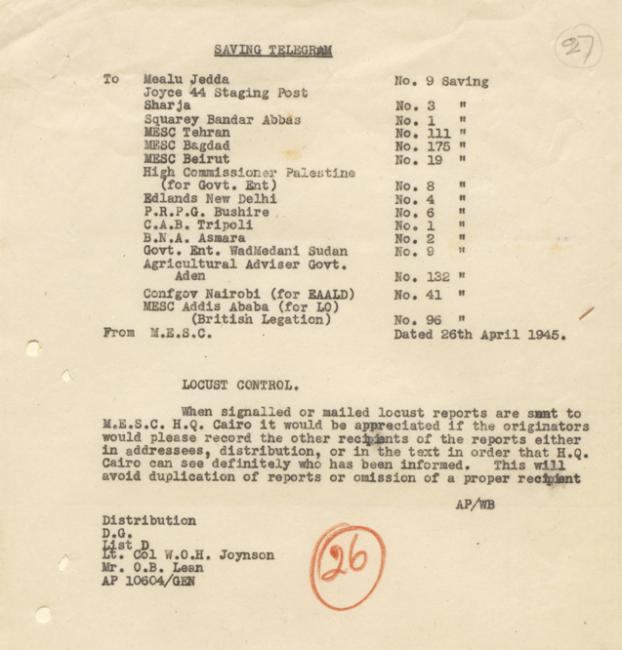

On 26 April 1945, as the war in Europe was coming to an end, a telegram was received at the Political Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. in Bushire whose list of recipients was longer than the main content of the telegram itself. During such extraordinary times it is understandable that so many places within a wide geographical scope might be sent the same information. The telegram’s heading, however, seems strangely unrelated to matters of war: ‘LOCUST CONTROL’.

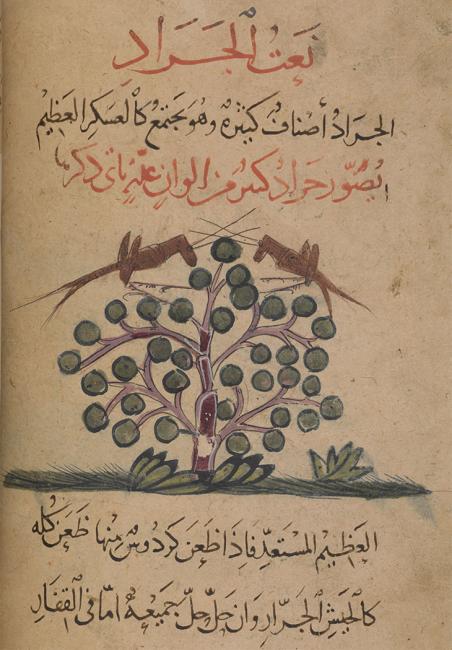

The Desert Locust

The communication reached British offices in other parts of the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. – Sharjah and Bandar Abbas were both contacted – as well as twelve other locations ranging from Delhi in the east, Tripoli in the west, and Nairobi to the south. Schisocerca gregaria, the desert locust, was a pest common to all these places. When occurring in small numbers it could be tolerated – as an edible delicacy it was even welcomed – but large swarms had been a scourge dreaded by the people of the Middle East, Asia and Africa for thousands of years. From the allegorical plagues of the Bible and Qur’an to the last major upsurge in West Africa in 2004 people have lamented the destruction this small insect has caused to crops and livelihoods.

The Locust Problem and Empire

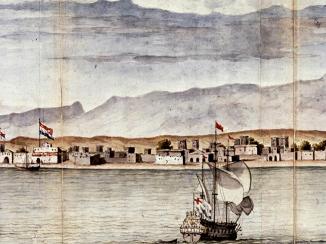

With breeding grounds along much of its coastline, the Gulf had long been at the heart of a locust problem that the British had been taking very seriously for over a decade. Ostensibly, locust control would help prevent famine and aid development, but ultimately it would make it easier to manage and maintain an empire. Acridology, the study of locusts, was thus encouraged and facilitated by the colonial powers in both London and Delhi.

Locust reports first became a regular part of colonial administration in the 1920s and 1930s, during acridology’s infancy. In June 1933, the Government of India requested that reports of locust occurrences in Muscat and Bahrain be sent each month. This request was soon extended to Sharjah and the Trucial Coast A name used by Britain from the nineteenth century to 1971 to refer to the present-day United Arab Emirates. . Detailed information was required – weather conditions, numbers, colours, behaviour, whether eggs were laid and whether they hatched – and the collection of specimens was encouraged so that experts could verify that it was the desert locust that had been seen.

Gathering Intelligence

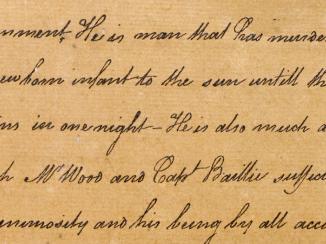

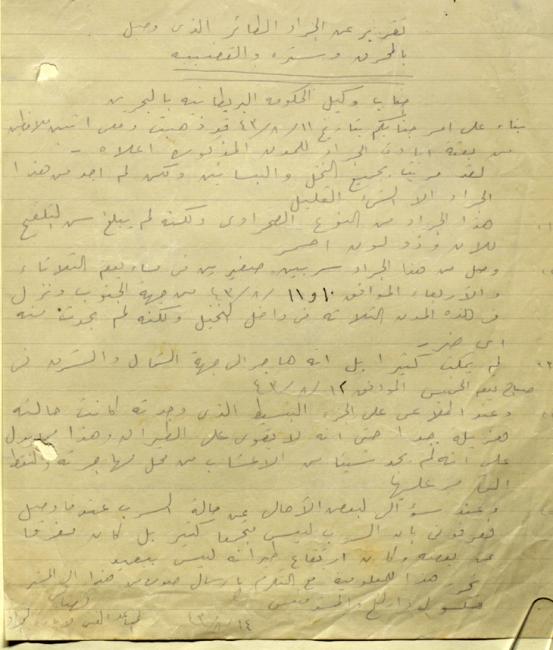

This called for a great deal of work, much more than the British administrators, few in number, had time or capability for. To assist with the task, several local people, sometimes referred to as ‘native agents’, along with those from neighbouring regions, were employed to gather intelligence on locust sightings in their area. Administrative evidence of this process, in the form of reports and handwritten office notes often found at the back of files, can be found in the files relating to the Bahrain Agency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, headed by an agent. .

Disruption of Supply Lines

The disruption of the Second World War coincided with a severe outbreak of desert locust. This posed a great threat to supply lines to the Middle East: any food shortage caused by locust swarms would need a large importation of relief aid that would depend on an already overburdened shipping network that was vital for military supplies. With the famines caused by locusts in Syria during the First World War still in living memory, the need to control the pest took on even greater importance for the British and their allies.

In 1942, the Middle East Anti-Locust Unit (MEALU) was established with the mission of nullifying locust swarms at the source: the breeding grounds. As a subsidiary of the Middle East Supply Centre (MESC), an organisation created to relieve the supply lines to and within the region, the importance of MEALU’s work was considered to be great, often second only to military operations. It boasted considerable financial support and inspired unprecedented international cooperation.

‘Combat’ Missions and Success

The first ‘combat’ missions were sent to Saudi Arabia, Iran, Yemen, Kuwait and Oman in 1943. The latter provided Wilfred Thesiger with his excuse to cross the Empty Quarter. In the winter of 1944, the Political Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. at Bushire was notified that a MEALU team was heading to Sharjah and onwards to northern Oman. The Resident, Geoffrey Prior, was asked to provide the party with accommodation and ‘other possible facilities’. By using poison bait and chemical sprays from aircraft, these missions were a great success, preventing any major outbreak in the region for the duration of the war.

The work required for the study and control of locust swarms called for significant international cooperation and involved people from many professional backgrounds and different countries – including those of the Gulf. The success they helped to achieve contributed to the Allied victory in the Second World War, yet it made no headlines and earned no medals or citations for anybody. The documents of the Bahrain Agency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, headed by an agent. and Bushire Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. contain a paper legacy of this largely forgotten war that helped to win the war.