Overview

In correspondence between HM the King and the Amir of Najd of 1920 it was noted that an animal ‘unique of its kind’ had arrived in London, indeed ‘no other specimen having reached England from Arabia alive’.

The person writing the note viewed the arrival of an oryx, presented by Ibn Saud, with some degree of national importance. But the manner in which the creature made its way to London had been challenging and circuitous.

The Oryxes’ Journey: Riyadh–Kuwait

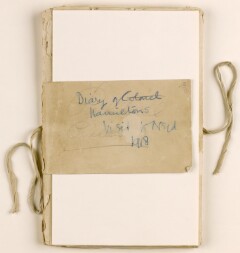

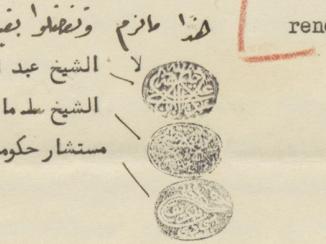

In November 1917, Lieutenant Colonel Robert Edward Hamilton was despatched with St. John Philby to Riyadh to discuss continuing tensions between Ibn Saud and Ḥusayn bin ‘Alī, the Sharif of Mecca. On Hamilton’s final day at Riyadh, Ibn Saud presented him with two Arabian oryxes – a male and a female – as a gift for King George.

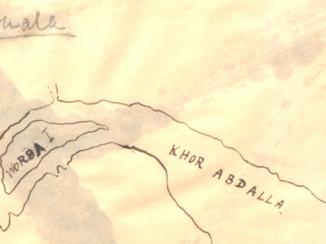

Hamilton left Riyadh on the morning of 5 December with the difficult challenge of transporting the two beasts back to Kuwait. He notes in his diary that two of the boys accompanying him eventually found a solution: ‘One leading both on a single rope and the other driving behind.’ Two days later he notes that the oryxes ‘now follow the sheep beautifully.’

After journeying for twenty-three days through the desert, Hamilton, who was severely ill by this point, arrived with the oryxes at Kuwait on 28 December.

Kuwait to London, via Bombay

From Kuwait, the pair of oryxes was sent to London via Bombay. Owing to the First World War, transportation from India to Europe was difficult and dangerous. Consequently, the oryxes were lodged at Zoological Gardens at Bombay where the male died.

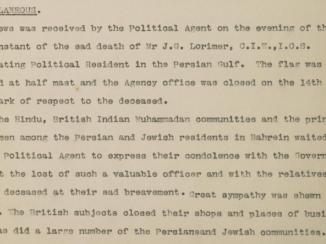

After almost three years, and long after the end of the First World War, a passage to England was secured for the remaining female oryx with Walter Samuel Millard of the Bombay Natural History Society. In May 1920, the oryx finally arrived ‘in excellent condition’ and Millard deposited her at the Royal Zoological Society in Regent’s Park.

The King’s Oryx at the Royal Zoological Society

According to a note entitled ‘The King’s Oryx’, the surviving female oryx possesses ‘a fine pair of horns’ and her ‘body is white, the whole of the forelegs and the lower part of the hind legs are brown with white fetlocks’. The white face has dark brown markings on the nose between the horns, on the cheeks and on the throat while a brown stripe runs down the chest’.

The note states that the ‘Arabs call the Oryx ‘Al Wathaihi’, which appears to be a rendering of the Najdi Arabic word al-wḍayḥī. The Arabian oryx is described as being ‘very shy and rarely seen’. The two oryxes presented as a gift had been captured young and brought up in Ibn Saud’s garden at Riyadh.

In fact, it is noted that Charles Doughty, famed author of Travels in Arabia Deserts never even saw one during his travels, and Sir Wilfrid Scawen Blunt and Lady Anne Blunt were in fact the first Europeans to see the Arabian oryx in its natural habitat.

The First Oryx in London and British Mythology

Although it is alleged that an Arabian oryx was brought to London by Captain John Shepherd in 1857, this may have been the first Arabian oryx to be transported to London alive.

According to common legend in both Arabia and Europe, the Arabian oryx appears to have only one horn when viewed on the broadside, and is therefore identified as the originator of the mythical unicorn. This fact appears to be significant since it would make this oryx ‘a living specimen of one of heraldic supporters of the Royal Arms introduced by Kings James I’.

Gift-giving and Diplomacy

The gift of the oryxes had further significance as a means of diplomacy. The practice of donating unusual, exotic or endangered animals still persists today, for example so-called ‘Panda diplomacy’ between China and the United States of America in the 1950s–1980s.

But the account of the difficult passage of the oryxes demonstrates that such a means of diplomacy was long common, both within Arabia and throughout the British Empire, between local rulers and British administrators. Gift-giving, particularly such rare and ‘unique’ animals, was understood as an attempt to solidify relations between rulers and countries.