Overview

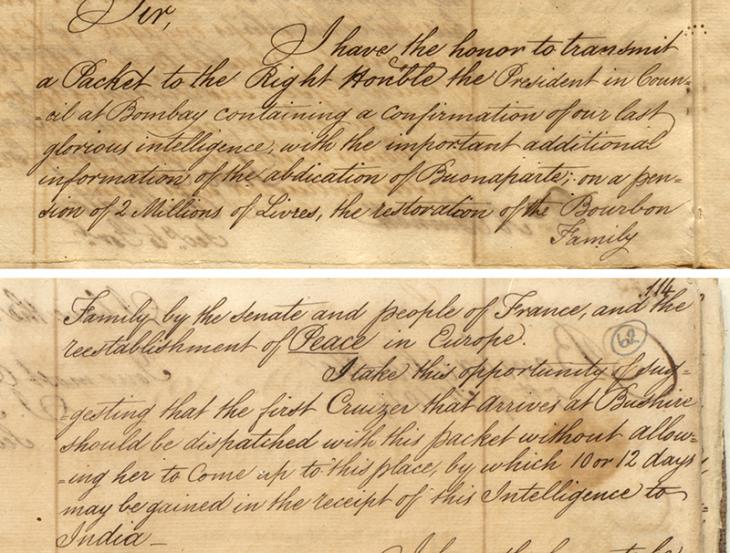

On 20 June 1814, a message received from London was forwarded with urgency by the Assistant to the British Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. , to Bushire and then to Bombay, India.

The message contained important information such as news of the abdication of Napoleon, the restoration of the Bourbon by the French, and the reestablishment of peace in Europe, signed on 30 May 1814 and known as the ‘Treaty of Paris’.

This news had taken twenty-two days to reach Basra from London. In 1814, at a time when mail was carried via horses, coaches and sails, covering almost 6000 kilometres in twenty-two days was a very impressive achievement. How did the message get there so quickly?

There were three main routes that the message could have taken. All three were part of the longer passage from London to Bombay.

The ‘All Sea-Route’

Initially, transmitting mail on East India Company (EIC) ships from London to Bombay by the ‘all sea-route’, via the Cape of Good Hope, was the longest and safest journey. Avoiding the risky waters of the The Gulf, EIC ships would sail from ports on the Channel, such as the Downs in Kent or Portsmouth. Contemporary sources report an average journey of one hundred and seventeen days.

The EIC maintained a monopoly on this route up until 1813, carrying private letters as well as ‘company’ mail. After 1814 the packet route (postal route) was open to merchant ships, but only for a few years. Certainly, this couldn’t have been the route our message took, because this route didn’t actually pass via Basra and took too long in any case, for the message to have arrived in twenty-two days.

The Quick but Impossible Route

The second route was the quickest, from London to Paris and then overland to Marseille (or Brindisi, a south-eastern Italian port), then via boat to Egypt, and from there overland to Basra.

The initial part of this route, overland via France, was dependent on the diplomatic relations between the two powers, so it wasn’t practicable during the Napoleonic Wars (1803–15), when England was at war with France. It is therefore unlikely that this was the route our message took in 1814.

The Falmouth Packet Service

The third option, which was certainly the safest in 1814, relied on the ‘Packet Service’, a mailing system based at Falmouth, on England’s south-western coast.

The ships sailing from Falmouth were themselves known as ‘Packets’, and were essential to maintaining communication between Britain and its colonies; especially in the West Indies. Maintaining commercial links to overseas interests was especially important at times of war. As a result, the Packet Service was extended to the Mediterranean when necessary, avoiding France altogether and relying on the good relations between Britain, Portugal and Spain.

In the first two decades of the nineteenth century, with the disruption of overland communication via France due to the Napoleonic wars, there were sailings from Falmouth to the Mediterranean every third Tuesday. The initial leg of the route was from Falmouth to Lisbon. The fastest journey recorded in that year was in May 1814, when the Sir Francis Freeling took just six days to reach Lisbon from Falmouth. Maybe our message was on this very ship?

Frequent Attacks

Speed was essential to free-flowing communication, but it wasn’t always easy. The Packets were small, lightly-armed ships and were subject to frequent attacks from pirates and privateers. Engaging in combat was not encouraged by the Packet Service, but returning fire under attack or fleeing was encouraged, according to John Beck, in his book A History of the Falmouth Post Office Packet Service 1689–1850, 2009.

At the time of the Napoleonic wars, a Packet, upon approaching a port, had to display ‘the White Jack [White Ensign] at the main topgallant masthead, an English ensign at the peak, and the ship’s distinguishing flag at the fore-top-gallant masthead’.

The Onward Journey

From Lisbon the message would have transferred to another ship, sailing to Malta and then Alexandria. The journey from Alexandria to Basra was overland. From Basra the message still had to be shipped to Bombay via Bushire, so that the news could be circulated by the Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. across the Indian sub-continent. In this way, important information could be circulated increasingly rapidly to the furthest reaches of Britain’s empire.

Communication in a Newly Global World: Around the World in Eighty Days!

The age of the Napoleonic wars was the moment communication started to become global; transmitting information and news from various corners of the empires become more important, indeed essential, for the main European powers.

Along with these momentous changes, travel times would radically change in just a few decades. From the 1820s onwards steamboats were more widely used, railways became commonplace and the Suez channel was realised. Indeed, such was the preoccupation with rapid travel that in his 1873 novel Jules Verne had the fictional Phileas Fogg travel between London and Bombay via Suez in just twenty days!