Overview

The monsoon winds have exerted their influence on the Gulf and Indian Ocean area for millennia, contributing to trade that in turn led to an intermingling of peoples and the creation of an Indian Ocean cultural network.

Monsoon System

Unlike the trade winds, which blow in a constant direction, the Indian Ocean monsoon blows from the south-west between April and September, and from the north-west between November and February. This had a profound effect on maritime trade in the Gulf. As Abdul Sheriff notes:

The monsoons imposed a regime that not only facilitated regular seasonal movements but also restricted it […] requiring dhows to spend a long time between the monsoons in their ports of destination.

Although most of the Gulf lies outside the direct influence of the Indian Ocean monsoon, for millennia, Arab seafarers had harnessed the seasonal reversal of the monsoon system to fill the sails of their dhows and travel out of the Gulf to Muscat and then onto Zanzibar, returning some months later.

In the age of sail, European fleets entering the Indian Ocean – at first the Portuguese and subsequently the Dutch, French and British – also learnt to use these winds to their advantage as they plied the routes between Europe and India.

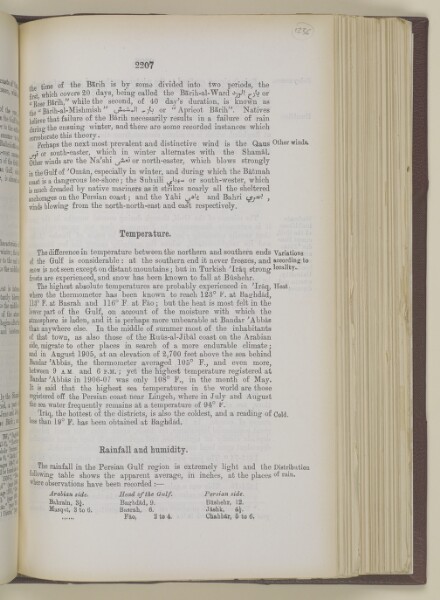

The Winds of the Gulf in Imperial Meteorology

European mariners were keenly aware of the winds in the Gulf that linked local seafarers to the monsoon system. The collection of data on meteorology was an important part of the British imperial information gathering process, a prime example of which is John Lorimer’s A Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. , Oman and Central Arabia, published in 1908 (Geographical and Statistical) and 1915 (Historical). He describes the characteristics and associated maritime dangers of the seasonal winds in the Gulf. It was essential that he record information for British administrators who would have been unfamiliar with what to expect from the seasons in the Gulf.

In particular Lorimer found it important to describe the prevailing north-west wind, known as the shamāl, which blows in the northern half of the Gulf for about nine months of the year. It is very strong in April and almost incessant in June. In summer the shamāl rarely exceeds the force of a moderate gale; in winter it is often fresh to a hard gale. Equally, other seasonal winds are described, including the kaus (or qaus), na’shi and suhaili.

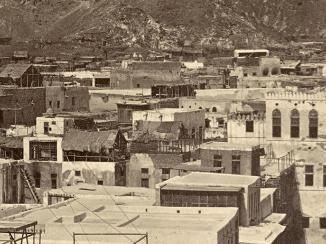

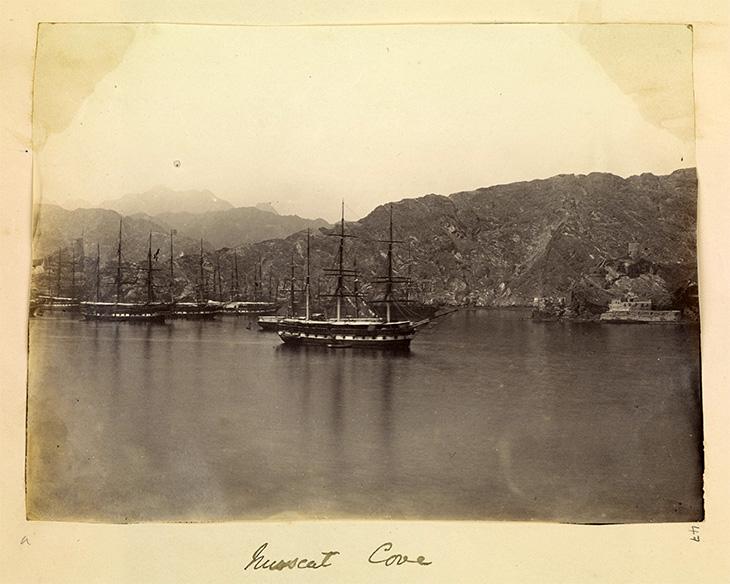

Muscat’s Role as a Port

Muscat had a particularly important role in the Indian Ocean trading network as it connected the Gulf and the Indian Ocean. Its location on the east coast of the Arabian Peninsula meant that it provided an ideal springboard for boats looking to ‘hitch a ride’ on the monsoon winds. Along with Sur, its position along the coast of the Gulf of Oman allowed it to play an entrepôt role for the Gulf, including the trade in slaves from East Africa. Many a British boat tasked with apprehending slave traders would turn up on the coast of Oman, only to find that the boats had arrived from Zanzibar a week earlier.

During the age of steamships, the constraints on travel by sea imposed by the monsoon began to diminish. As steamships replaced sailing ships in the mid-nineteenth century, Muscat became a port of call for the British-Indian Steam Navigation Company. However, measures taken by Britain to curb the trade in slaves and guns meant that Muscat was declined as a port and as a regional maritime power in the second half of the nineteenth century. The U.S. consulate closed in 1915 and the French did not replace their Consul when he died in 1918.

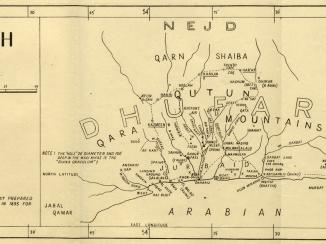

Matrah and Dhofar

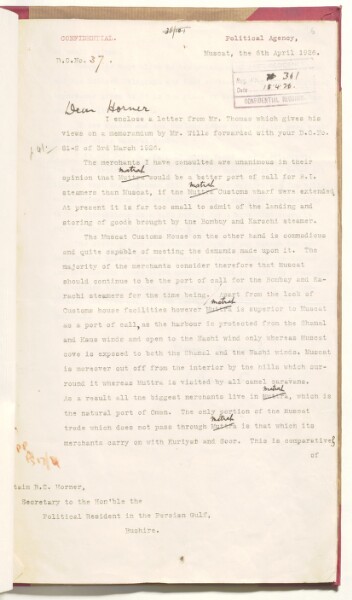

Due to this decline in importance, discussion ensued in the 1920s on a proposal to change the port of call for British Indian ships from Muscat to Matrah. Bertram Thomas, the Sultan of Muscat’s Finance Minister, argued that the Batinah region formed a natural hinterland for Dubai. As Dubai’s pearl wealth increased, so too did its purchasing power: as a result, caravans from the Batinah region could trade more profitably with traders in Dubai than with those in Muscat.

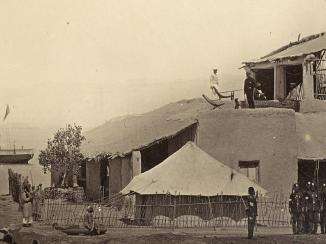

Muscat’s decline as a port was not due to any changes in the natural environment but rather due to the smothering nature of British imperial influence, which eroded the financial potential of the Sultan of Muscat by curbing his trade in guns and slaves. Unable to buy tribal loyalty he became vulnerable to attack from tribes of the mountainous interior leading the British Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. , Major Barrett, to conclude:

I do not mean to imply by these views that I anticipate the early demise of Muscat. I do not consider it to be at all likely that His Highness will change his residence. The hills, which detract from [Muscat’s] desirability as a port, add considerably to its attraction as a safe refuge for a somewhat insecure ruler among a turbulent people.

Throughout the twentieth century the impecuniosity of the Sultans of Muscat fuelled resistance against their rule. This required ever more frequent interventions of British military support to quash insurgents who found refuge in the mountainous regions: firstly, on the high plateau of the Jabal Akhdar and then later in Dhufār, 1965–75.

In Dhufār an additional complicating factor in the attempts of the Sultan’s Armed Forces to dislodge their opponents were the seasonal changes brought on by the climate, unique in Arabia. As recorded by Lorimer, Dhufār, by contrast to other regions in Oman, received the full effects of the monsoon.

As a result, each rainy season, the mountains of Dhufār are transformed from brown to luxuriant green. This natural cover allowed rebel fighters to return to areas from which they had been expelled, leading one writer The lowest of the four classes into which East India Company civil servants were divided. A Writer’s duties originally consisted mostly of copying documents and book-keeping. to dub it the ‘Monsoon Revolution’. In the tense stand-off between centre and periphery in Oman, the physical environment had come into play, once again.