Overview

It’s hard to imagine a natural resource as important to the history of the development of the Gulf States as oil. But in the early days of oil exploration, nothing was more important than water.

The importance of oil to the Arab states of the Gulf is well-established. The region’s states have experienced continued and dramatic transformation since the first oil exports in the mid-twentieth century. Less attention, however, has been given to the importance of water to the inhabitants of the Gulf.

On one hand, it is unnecessary to state water’s timeless importance; for drinking, cooking, cleaning and washing, and for agricultural production and livestock feeding. But on the other, the rapid urbanisation of the Arab coast’s towns from the early 1950s onwards – in step with the growth of the oil industry – demanded more water than the region’s meagre natural resources could supply.

Underground Sources and Brackish Wells

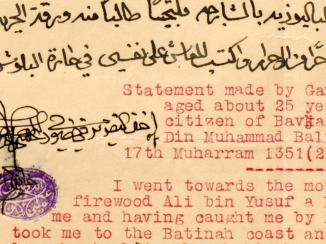

Historically, both the Bedouin tribes who lived inland, and the coast dwellers of the Arabian Peninsula, obtained their water from underground sources. The British explorer Wilfred Thesiger, one of the first Europeans to cross the Arabian Peninsula’s ‘Empty Quarter’, recounted how the trade routes across the desert were dictated by the location and distance between wells. Nothing could be as dispiriting as arriving at a well at the end of a long day’s travel, only to find that its water was of such a poor quality as to be virtually undrinkable.

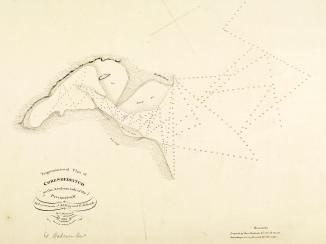

Most coastal villages had a well, and any town of significant size had several. The quality of water obtained was usually measured by its brackishness, or salinity, and varied from one well to the next. In larger settlements the location and quality of wells influenced the patterns of urban growth, and the social distribution of inhabitants.

Water Sources in Bahrain

In the case of Manama, Bahrain’s principal town, Lorimer’s Gazetteer states that ‘the better classes at Manama buy their drinking water from the camelmen of Rifa’-ash-Sharqi and Rifa’-al-Gharbi who bring it for sale from the Hainini and Umm Ghawaifah wells of their respective villages’.

Meanwhile, ‘water used by the poorer inhabitants’ was procured from two brackish wells, one ‘about one mile west of the town’s fort, filled by the surplus water of several springs; the latter sunk in the coral rock between the British Political Agency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, headed by an agent. and the American Mission’. The water quality of this last well was deemed insufficient for the British Agency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, headed by an agent. , the result being that their drinking water had to be imported from Bombay by steamer.

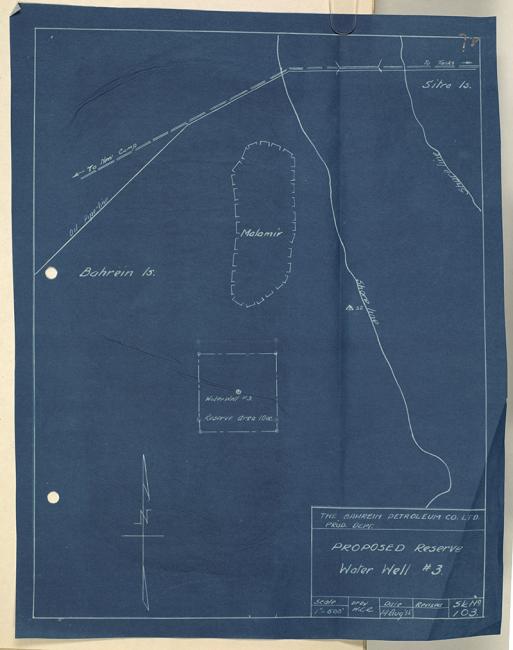

Deep-water Wells

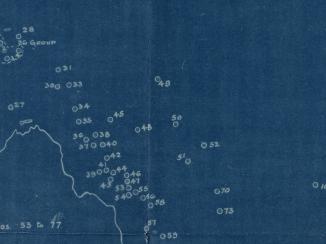

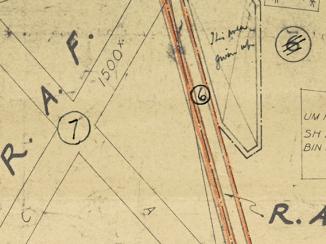

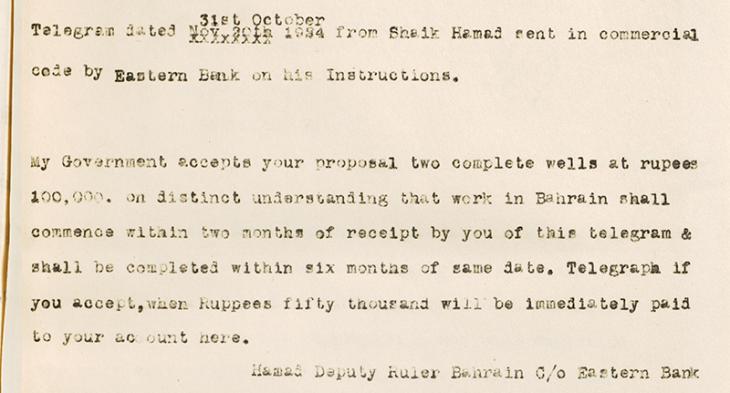

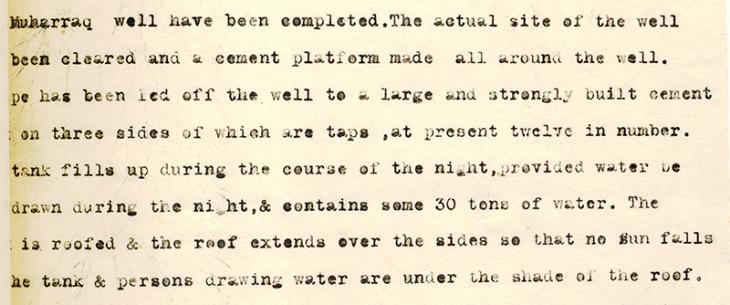

In 1924, the Eastern and General Syndicate of London, under the direction of Major Frank Holmes, began drilling two water wells in Bahrain; one in Manama and the other on the island of Muharraq. The project’s geologist, Mr Madgwick, reported that good-quality water had been found at a depth of two-hundred feet in Manama. Shortly afterwards, a cement platform and water tank capable of holding thirty tonnes of water were installed by the well.

Major Clive Daly, the British Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. in Bahrain, observed that the tank was emptied out in just three to four hours each morning. The immediate main beneficiaries of the new wells were the gardens of Manama’s new residential suburbs, as well as the wider urban population. The Bahrain Government commissioned Holmes to drill a further twelve wells around Bahrain, all of which were completed between 1925 and 1927. The new wells were also of great benefit to Bahrain’s date industry.

‘The Wealth of Bahrain Lies in the Water!’

Holmes, who was principally in Bahrain to negotiate oil concessions with the Bahrain Government on behalf of U.S. companies, remarked to Daly that ‘the wealth of Bahrain lies in the water!’

Holmes’s comment might seem a little odd, but aside from its importance to domestic and agricultural activities, water was also essential to the oil industry. It was required when drilling, to help clear the drilling area of debris and cool the drilling apparatus. It was also required during extraction, because the injection of water into the oil reservoirs increased pressure and improved production. Water was also used in the processes of distillation.

In the Gulf, oil companies first had to drill for water, and then construct water supply facilities, before they could begin drilling in earnest for oil. The construction of a water supply infrastructure for industrial purposes helped create revenue for the oil companies, which in turn enabled the Gulf States to invest in bigger, better water facilities for their domestic populations.

Nearly one-hundred years after Frank Holmes drilled his water wells in Bahrain, the question of how to meet the Gulf Arab states’ ever-growing demands for water continues to present a challenge. But while Holmes looked for his solution underground, today’s scientists are looking to the Gulf itself, and the large-scale desalination of its seawater.