Overview

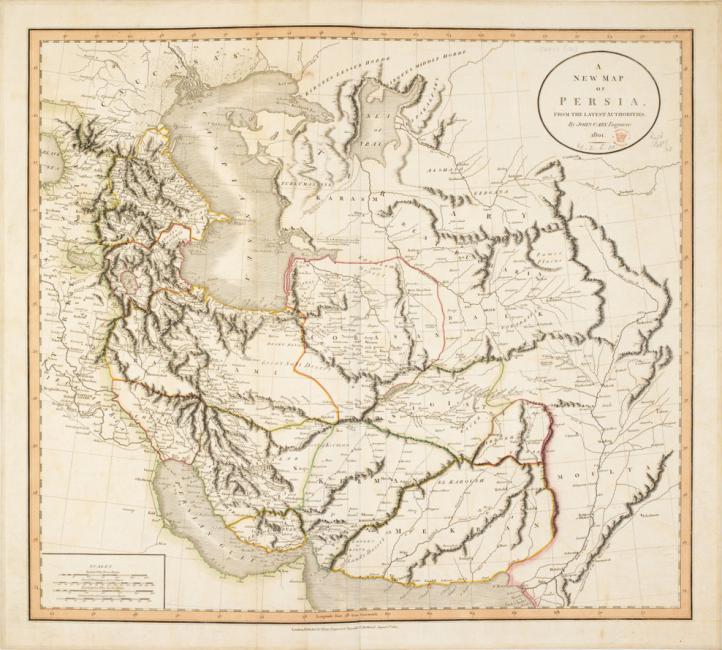

In the early nineteenth century, Britain increasingly came to view Persia as a crucial partner in the strategic defence of India’s North-West Frontier Region of British India bordering Afghanistan. . Already fearful of threats from both France and Russia, Britain hoped to create a buffer zone to protect British India. To that end, the British sought to strengthen Qajar Persia with money, materiel, and troops.

North-Western Frontiers

At this time, Persia was having trouble on its own north-western frontier. War had broken out between Russia and Persia in 1804 over the latter’s Caucasian provinces. The war awakened Persia to the need for military reform: there was no permanent standing army, and military organisation along tribal lines engendered disadvantages against professionally organised Russian troops.

Following setbacks at the outset of the war, the Crown Prince ‘Abbas Mirza believed that the best solution would be to reform the armed forces along European lines. Another important consideration for him was the possibility of internecine conflict over the succession; a European-trained and equipped army would likely strengthen his position.

Persia had successfully negotiated military assistance from France in 1807, and had received a small detachment of officers in December of that year, who provided training and equipment for ‘Abbas Mirza’s troops. Fearing a Franco-Persian invasion of India, the British had dispatched envoys, resulting in the ratification of a Preliminary Treaty in June 1809. Revised in 1812 and 1814, the treaty provided for a subsidy paid by the East India Company to train and equip the Persian armed forces.

‘What can I do with Tobacco and Sugar?’

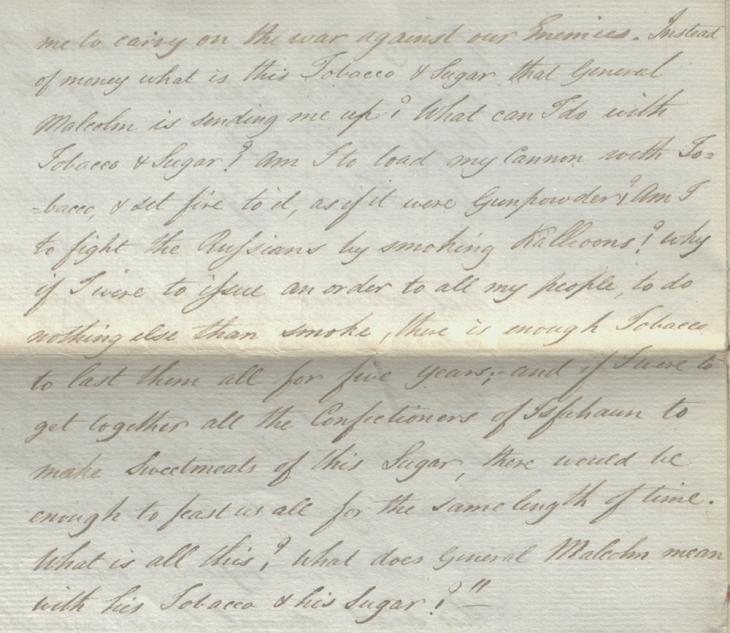

In January 1810, the newly appointed Ambassador to Persia, Sir Gore Ouseley, was authorised to provide an annual subsidy of 200,000 tomans 10,000 Persian dinars, or a gold coin of that value. . However, not all of the payments came in the expected form: in May 1810 ‘Abbas Mirza complained to Sir Harford Jones, Ouseley’s predecessor, about receiving payment in the form of tobacco and sugar.

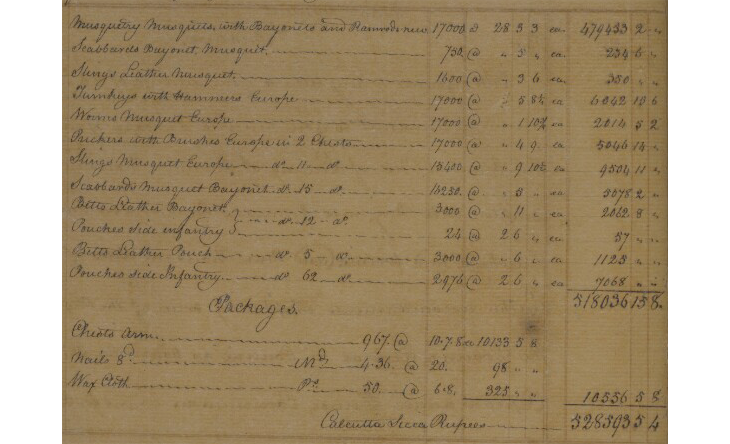

The British also began exporting weapons to Persia. An invoice received by the Acting Resident at Bushire [Bushehr], William Bruce, in November 1812, records 17,000 new muskets bound for Bushehr from India aboard the East India Company’s ship Lord Minto. By the end of the war, ‘Abbas Mirza had received a further twenty cannon and 1000 sabres as a gift from another British envoy, Brigadier-General John Malcolm. In addition to transporting weapons, the British also established an arsenal at Tabriz for the production of cannon, gunpowder, and ammunition.

Progress Pleases the Persians

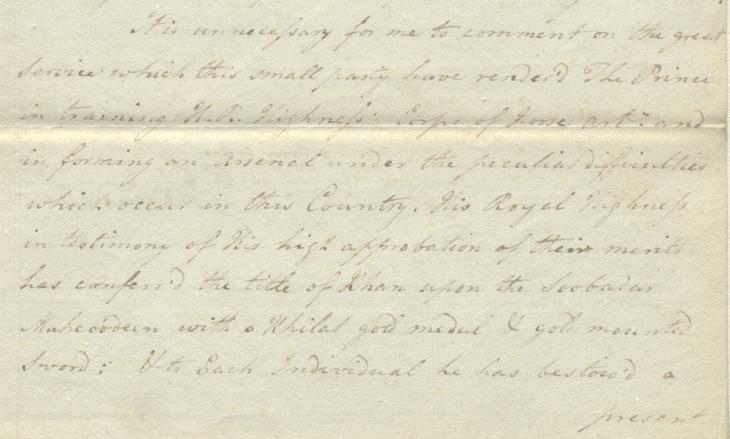

In addition to funding and equipping the Persians, the British sent a small mission of officers and soldiers to train ‘Abbas Mirza’s troops using European methods. The nucleus of the mission was formed in 1810 with Lieutenants Charles Christie and Henry Lindsay, and Ensign William Monteith from Malcolm’s entourage remaining in Persia after his departure. They were joined by Henry and George Willock from Jones’ 1808 mission, and later by troops from the Royal Artillery, the Royal Engineers, and the 47th (Lancashire) Regiment, swelling the mission’s ranks to over fifty. Their number was further supplemented by Indian soldiers, who were decorated by ‘Abbas Mirza for training a unit of horse artillery.

By 1812, ‘Abbas Mirza boasted an army of approximately 13,000 troops. In January that year, Ouseley reported to the Governor-General of India, Lord Minto, that the Persians considered their forces ‘greatly improved and strengthened by the introduction of European discipline’ (IOR/L/PS/9/68/122, f. 3v). Moreover, the Shah, Fath ‘Ali Shah Qajar, was so pleased with the mission’s progress that in March he informed Ouseley of his intention to raise an army of 50,000 troops for ‘Abbas Mirza, placing an order for 30,000 British muskets (IOR/L/PS/9/68/128, ff. 1r-1v).

On Campaign with ‘Abbas Mirza

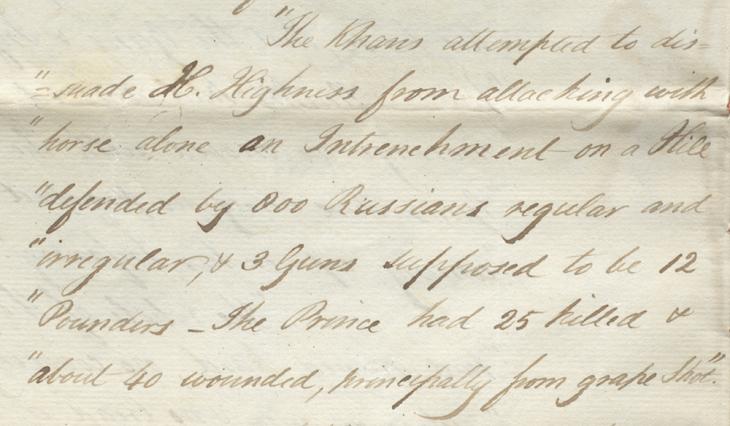

British troops also joined ‘Abbas Mirza’s armies on campaign. Christie, Lindsay, and Monteith accompanied ‘Abbas Mirza to the Erivan Khanate in the late summer and autumn of 1810. In a letter to Jones, Christie details long marches and heavy rain, reporting several unsuccessful attacks by Persian troops against Russian entrenchments.

At the beginning of 1812, Christie, Lindsay, Major Joseph D’Arcy of the Royal Artillery, and George Willock were part of a renewed and more successful campaign, taking part in the Persian victory at Sultanabad on the River Aras in February. The victory represented the successful use of the newly trained, European-style infantry by ‘Abbas Mirza, in which the British detachment played an important role: Christie and Lindsay led the Persian infantry, while D’Arcy directed the artillery.

War’s End

Despite the success at Sultanabad, ‘Abbas Mirza’s forces suffered a heavy defeat on the north bank of the Aras at Aslanduz on the night of 31 October 1812. A force of approximately 5000 infantry, led by ‘Abbas Mirza himself, was caught out by a smaller Russian force and suffered heavy casualties. Christie was killed in the fighting. In January 1813, the Russians stormed the Persian fortress at Lankaran on the Caspian coast, taking no prisoners.

Meanwhile, Napoleon had invaded Russia in June 1812, causing the British to reconsider their support for Persia. Russia was a vital ally for Britain against Napoleon, and the British military presence in Persia was increasingly incompatible with the broader war against Napoleonic France. Ouseley pressured the Persian Government to seek peace with Russia, and following British mediation, they signed the Treaty of Gulistan in October 1813. This saw Persia cede large swathes of its territory in the eastern Caucasus, including much of the modern-day states of Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan, and the Russian Republic of Dagestan.

Mission’s End

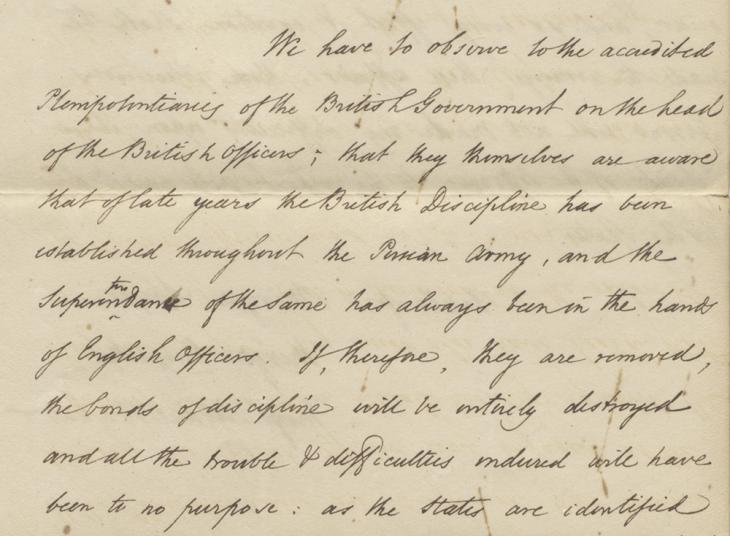

Following the Treaty of Gulistan, the British began to run down the mission. During negotiations in November 1814 to amend their respective treaty commitments, the Persians appealed to the British to maintain their support.

However, by 1815, subsidy payments to Persia had ceased, and the majority of the mission had been withdrawn. Only a handful of British troops remained in Persia, under orders not to take part in operations against any country with whom Britain was at peace, namely Russia.

Persia Loses the Caucasus

Tensions remained high in the Caucasus following the humiliating terms of the Treaty of Gulistan, with war breaking out again in 1826. Despite their treaty obligations, the British refused to lend any support. Following defeat in 1828 and the subsequent Treaty of Turkmenchay, Persia ceded the last of its remaining Caucasian provinces to Russia.

‘Abbas Mirza’s ambitions and Britain’s assistance ultimately failed to check Russian expansion into the Caucasus. Despite the Anglo-Russian detente in 1812, Russian growth increasingly concerned the British throughout the nineteenth century. Fear of a Russian attack on India led to further British diplomatic and military involvement in Persia, part of what has become known as the ‘Great Game’. The 1810-1815 mission might have been an early example, but was not the last of such interventions over the following centuries.