Overview

In 1779, the ruler of Persia and founder of the Zand dynasty, Karim Khan Zand, died of natural causes without nominating a successor. Karim Khan (referred to in the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. Records as Carim Caun) had ruled Persia for the previous thirty years and his failure to appoint an heir immediately created a dangerous power vacuum in the country.

A number of rivals from within his own family emerged. The most prominent contenders initially were Karim Khan’s half-brother Zaki Khan Zand (Zackey Caun) and his brother Sadiq Khan Zand (Sadoo Caun or Sadoo Khan).

Zaki Khan and Sadiq Khan

Zaki Khan was a powerful and ruthless warrior who – as a general in the service of Karim Khan – had brutally suppressed Qajar tribal territories in the north of Persia in 1763–64. He had even attempted to form a personal fiefdom in central and southern Iran. Although he was the head of a faction that claimed to support the ascension of one of Karim Khan’s infant sons, Mohammad Ali Khan Zand (who was married to Zaki Khan’s daughter), it was clear that he harboured intent to rule in his own right.

Sadiq Khan was also a prominent member of the Zand ruling elite and had led the Persian attack on Ottoman-controlled Basra in 1775–6. He was part of a faction that stood in opposition to Zaki Khan and supported another of Karim Khan’s infant sons, Abol Fath Khan Zand, to succeed his father.

Both of these rivals had military experience and armed followers. Serious tension swiftly developed between them and the prospect of a major confrontation between their forces loomed.

As John Beaumont, the East India Company’s (EIC) Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. in Bushire, observed in a letter dated 11 May 1779, this tension would not end ‘but with the death of one of them’.

The British Get Word of the Death of Zaki Khan

Beaumont’s observation proved to be prescient as not long after, he received news from Shiraz (referred to here as Schyras) that Zaki Khan had been killed at the hands of his own men.

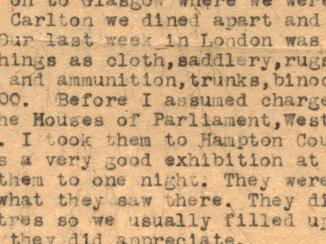

In a letter dated 23 June 1779 he described the event to William Hornby, the Governor of the EIC’s Council in Bombay. Beaumont states that it has ‘pleased the almighty to save Persia and rid the world of such a cruel monster’. The letter describes in gruesome detail how, after Zaki Khan had ordered a massacre of villagers while on the move with his army, his generals were so outraged at his actions (and concerned for their own lives) that they conspired to kill him.

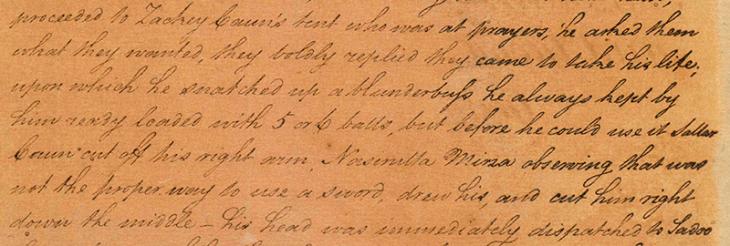

Beaumont’s account explains the death:

[the conspirators] proceeded to Zackey Caun’s tent who was at prayers, he asked them what they wanted, they boldly replied they came to take his life, upon which he snatched up a blunderbuss he always kept by him ready loaded with 5 or 6 balls, but before he could use it, Jaffer Caun cut off his right arm. Nasirulla Mirza observing that was not the proper way to use a sword, drew his and cut him right down the middle.

His head was then cut off and immediately despatched to Sadiq Khan before his body was burnt. Concluding his letter, Beaumont stated that ‘as soon as Sadoo Cahn returns to Schyras the Persians have not a doubt but peace will be restored everywhere and affairs conducted quietly again in their usual channel’.

Beaumont Hopes for Renewed Stability

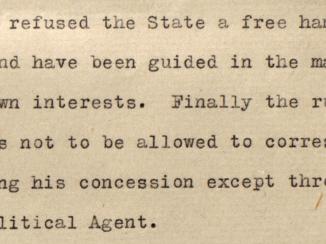

After Zaki Khan’s death, Sadiq Khan was in the ascendancy. In a letter dated 20 November 1779 Beaumont was able to report that ‘Sadoo Khan maintains his power at Schyras and seems at present to be firmly established in power’.

He was keen for political stability to be restored in the country so that the EIC could resume its activity in the silks and woollens trade. Unfortunately, Beaumont was to be disappointed as Zaki Khan’s brutal killing turned out to be the first of many others.

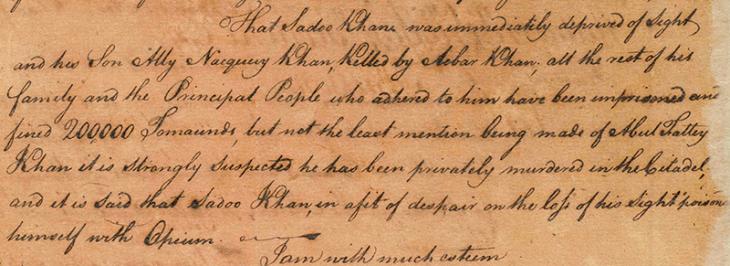

Rather than marking the start of a new period of calm under the rule of Sadiq Khan, it instead marked the beginning of a brutal internecine struggle from which the Zand Dynasty never recovered. Despite his dominant position in 1779, two years later, Beaumont learnt that Sadiq Khan had been defeated and blinded by another rival for power, Ali Murad Khan (here referred to as Ally Morad Khan), and that ‘in a fit of despair on the loss of his sight’ he had poisoned himself with opium and subsequently died.

Further Deaths and the Rise of the Qajars

Ali Murad Khan ruled from 1781 until 1785 when he, in turn, was defeated and killed by Sadiq Khan’s son, Jafar Khan. Throughout the 1780s and early 1790s, the Qajar tribe in the north of Persia grew in power and began to threaten the Zand dynasty’s rule.

By 1794, the Qajars were dominant and Lotf Ali Khan, son of Jafar Khan and the last Zand ruler of Persia was defeated and killed by Mohammad Khan Qajar, the Chief of the Qajar tribe. This event marked the beginning of the Qajar Dynasty’s rule over Persia, a period of domination that was to last until 1925.