Overview

When Lewis Pelly arrived in Bushire as Britain’s senior official in the Gulf, the region had seen nearly two decades of considerable growth. But by the time he left for India in 1872, only ten years later, output had collapsed. The region was in economic turmoil. What went wrong?

Astounding Growth

When he became Britain’s Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. in the Gulf in 1862, one of Lewis Pelly’s priorities was to increase trade, as this would benefit Great Britain and its empire. The picture in his early tenure was extremely positive.

Trade was expanding rapidly. Merchants were transporting goods through the region. Output was growing and new wealth was being created. The Gulf was an excellent place to do business.

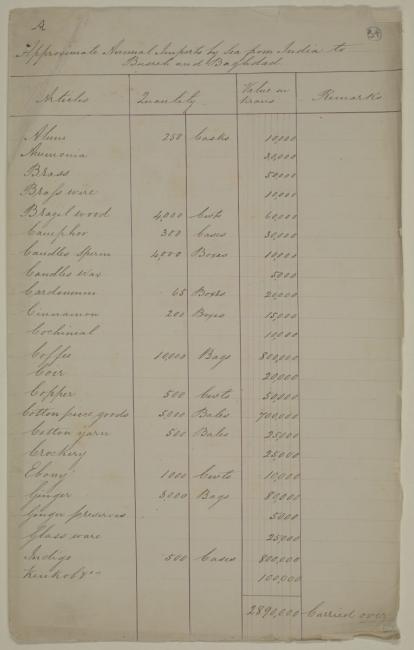

In 1866, Pelly told his superiors in the Government of Bombay From c. 1668-1858, the East India Company’s administration in the city of Bombay [Mumbai] and western India. From 1858-1947, a subdivision of the British Raj. It was responsible for British relations with the Gulf and Red Sea regions. : ‘Trade which in 1846 represented in the gross somewhat under half a million sterling is now upwards of five millions’. These figures, although estimated, suggest a staggering 1000% increase in the value of seaborne trade in the Gulf in just twenty years. In today’s prices, that would mean the region’s trade was worth £500 million. What drove this growth?

Telegraphs, Pearls and Cotton

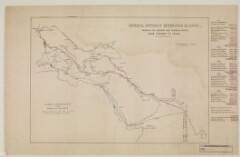

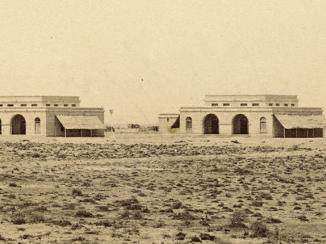

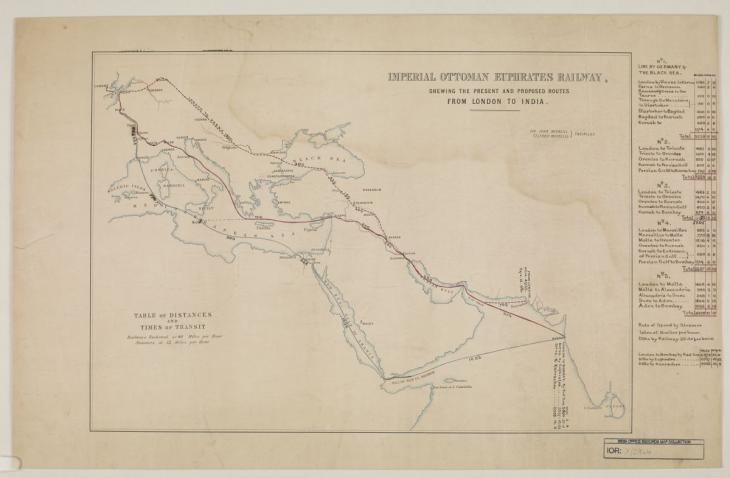

In the nineteenth century, the region witnessed a significant change in means of communication. The extension of telegraph lines, particularly throughout the Persian side of the Gulf, heralded a new era of long-distance communication. Whereas information contained in a letter could take a month to travel between Bushire and Bombay, it could take less than ten days to be conveyed in a telegram. Commercial companies and governments could coordinate their business with little delay.

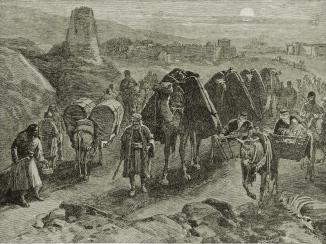

Trade was transforming the seas too. Steamer routes were increasingly calling at the Gulf and Aden en route to and from India. With many more steamers calling at Muscat, Gwadar, Kuwait and Bushire, merchants could ship goods to India, the Far East and Red Sea ports much more expediently than overland, and in much greater volume than caravans could take overland.

Geographical and environmental factors played a part too. The cotton famines in India (1860–65), for example, were hugely beneficial to Persia. Where previously cotton had only been produced for local use, suddenly the value of cotton was so high that shipping it to India became cost effective.

When droughts or a plague of locusts devastated crops elsewhere, the Gulf’s corn trade experienced a boost. Merchants looked to trade with producers in the Gulf to ensure that they had a supply sufficient to meet the empire’s demands.

With improved transport and communications, lucrative trades grew rapidly. Pearling as well as horse-dealing were particular to the Gulf. In 1866, pearling was worth approximately £1–2 million a year, with Bahrain and Kuwait being two of the biggest exporters of pearls. Horse-dealing was a highly lucrative business as Arab horses were much admired by British civil servants in India. By this time the Gulf region had witnessed an extraordinary boom, but the good times could not last forever.

Political and Economic Turmoil

Politics and civil unrest were key issues that impacted upon trade towards the end of Pelly’s years as Resident. Trade at Bushire prospered as long as the relationship between the Resident and the Persian Government was civil. This was one of the key ways in which Pelly was able to promote trade. Import and export duties were often imposed or increased when relations were strained. This caused merchants to choose alternative ports to trade from or to avoid the Gulf region altogether. So it was in 1866 when a dispute over fruit being brought overland into Bushire for export by sea led to a hike in import duties on specific items, such as watermelons.

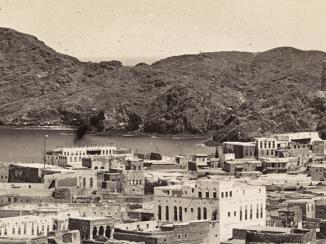

Muscat was also central to trade in the region. In 1865, the Omani port descended into a state of crisis, compounded by the Sultan’s death in 1866. Two years later his son and successor was overthrown. Amid the turmoil, British Subjects were withdrawn from the city. When steamers refused to call there, trade was paralysed and imports and exports across the Gulf were badly hit.

The Threat of Piracy

The region was buffeted by global events and piracy was another issue that affected the value of trade in the Gulf. In the 1860s, the British Government decided to concentrate its naval forces on suppressing slavery in East Africa. This left steamers and trade vessels in the Gulf vulnerable to piracy, causing some to take their business elsewhere.

Merchants and British Subjects were hesitant about residing in and trading with the Gulf ports because they did not trust the Government to pay reparations should something should happen to them or their goods.

Famine and Pelly’s Final Years as Resident

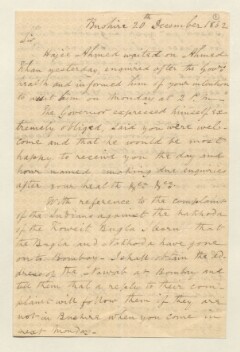

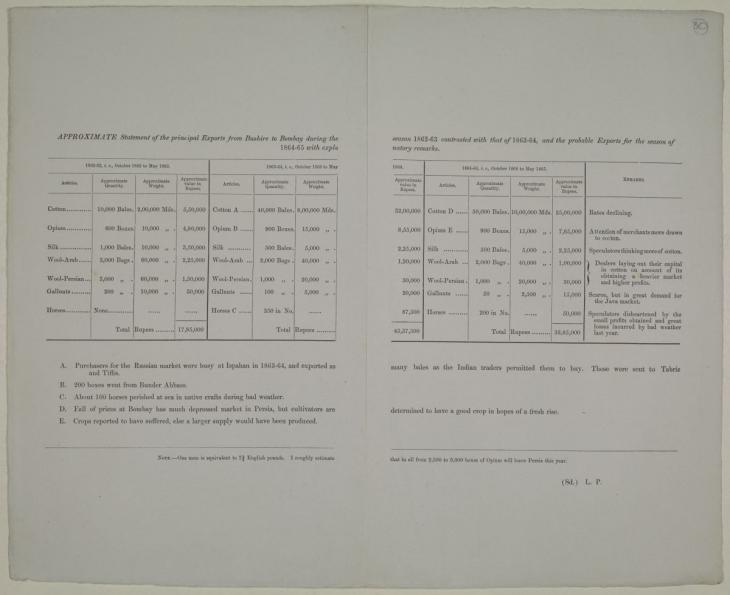

By the time Lewis Pelly left his post as Resident in 1872 to return to India, the situation was becoming increasingly difficult, particularly in Bushire. The local population was in the grip of severe famine, which some estimates suggest killed two million people. Corn and other crops required for subsistence and trade were in short supply. Disease spread.

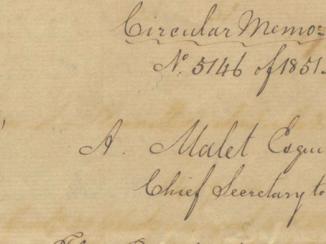

In the turbulence, the agricultural output of Bushire and its surrounding province collapsed. In 1872, output was expected to be no greater than a quarter of the previous year’s. Pelly received notification of this in a letter dated October 1871, which read, ‘the cultivation will be 75% less than the average of former years’.

There were greater concerns too: reports from elsewhere in Persia told of rising grain prices and fears that the coming winter would bring more severe famine. Even the large quantities of food-stuffs and other goods being imported from India would not be able to make up for the shortfall in agriculture and trade.

From an initial position of growth, Pelly had witnessed an astonishing economic collapse across the region during his ten years as Resident.