Overview

An Overview of the Gombroon Factory

Gombroon, the name by which the English referred to Bandar-e ‘Abbas, is a port town on the northern coast of the Gulf. The name Gombroon was an adaptation of the Portuguese Cambarão or Comorão, themselves adaptations of the Persian and Turkish word gümrük meaning ‘Customs House’. In 1623, following the expulsion of the Portuguese from Hormuz and Bahrain, and the growing interest of the East India Company (EIC) in the region, the Company established a Factory An East India Company trading post. at Gombroon to administer its trading activities on the northern coast of the Gulf. Soon after, the Gombroon Factory An East India Company trading post. became the centre of British trade and political activities in the region.

A Chief Agent headed the Factory’s decision-making ‘Council’. The Council members coordinated with Factors, Brokers, and local partners at the rest of the British establishments in Persia, primarily in Isfahan, Kerman, and Shiraz. From 1635 onwards, they also coordinated with the EIC’s Resident at Basra, who was in direct contact with Ottoman and British officials in Baghdad, Aleppo, and Istanbul, as well as officials in British India.

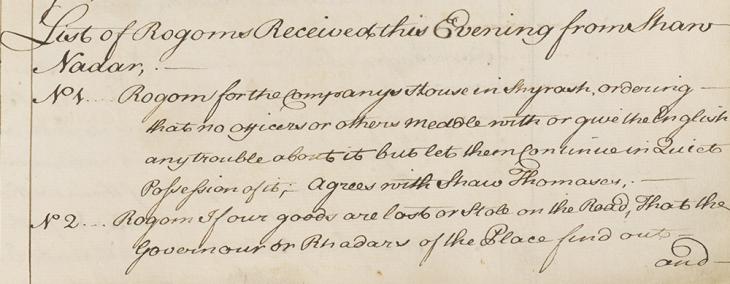

In many ways, the Factory An East India Company trading post. owed its existence and commerce in the region to certain royal grants confirming specific trading privileges known as rogums [ ruqum Royal grants confirming specific trading privileges from the Shah of Persia. or raqams Royal grants confirming specific trading privileges from the Shah of Persia. ]. These were granted to Britain by the Shah of Persia, and were renewed when it became necessary, whether through change of dynasty, ruler, or other circumstances.

The Gombroon Factory An East India Company trading post. and other British establishments’ functioning was often affected by the status both of trade and of the overall political conditions. Examples of these are plentiful, including the series of Afghan invasions starting in 1722, the murder of Nadir Shah in 1747, as well as the constant military operations in the region. Such events caused the British establishments to shut down temporarily and sometimes permanently. In 1763, due to the decline in the status of Gombroon and the ongoing unrest in the town, the Gombroon Factory An East India Company trading post. closed, and its duties were passed on to the British establishments at Basra and Bushehr.

The Structure of the Gombroon Diaries

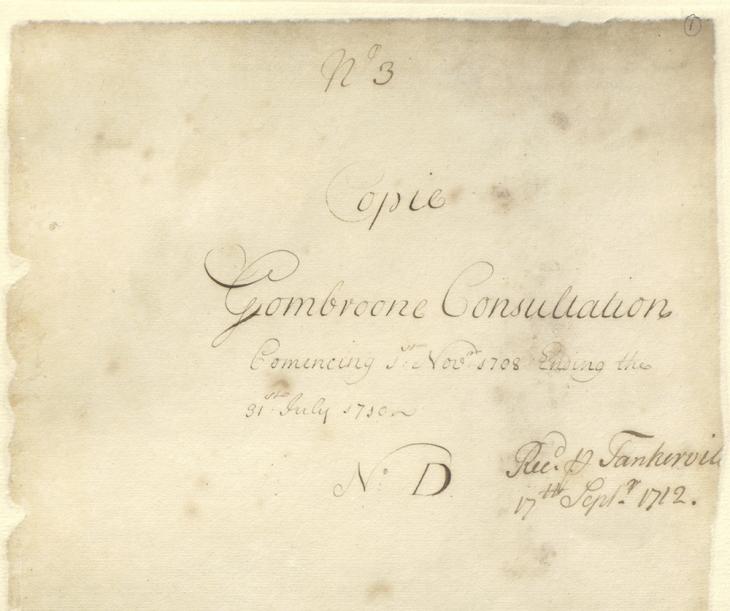

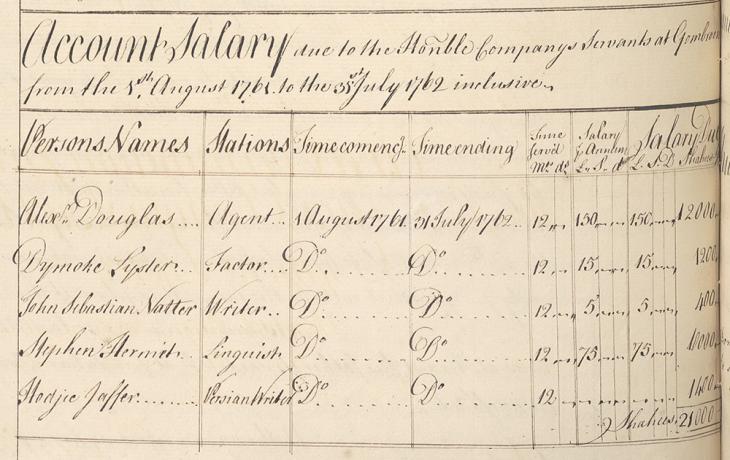

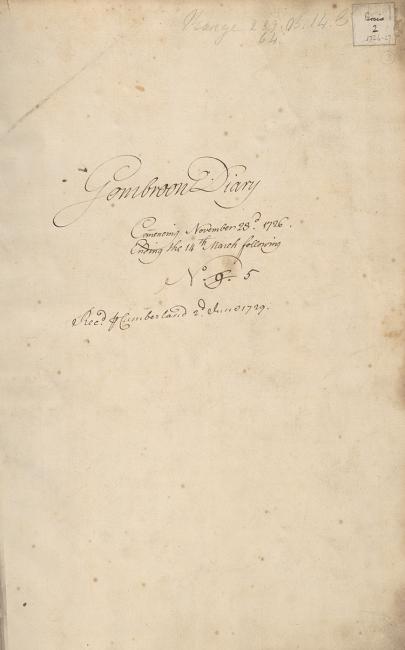

The consultations at the Gombroon Factory An East India Company trading post. were recorded in diaries. Each diary usually covered a one-year period. Copies of the diaries were dispatched by sail to the Company’s administrative headquarters in the Bombay Presidency The name given to each of the three divisions of the territory of the East India Company, and later the British Raj, on the Indian subcontinent. . The surviving thirty-two Gombroon diaries provide a window into the social, political, and economic history of eighteenth-century Persia and the Gulf.

The surviving diaries are bound within thirteen individual volumes that are classified under the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. Records’ (IOR) sub-series IOR/G/29/2-14. These are dated from November 1708 to February 1763. Any lacunae within these two dates indicate that the diary either did not exist in the first place, or was lost, misplaced, or removed from the records at some point. Most of the volumes include one diary each, apart from volumes IOR/G/29/5, 6, and 7, which contain nine, seven, and six diaries respectively. Some of these diaries include a table of contents at the beginning of the volume.

Topics Covered in the Diaries

The Gombroon Diaries record the consultations that took place at the Factory An East India Company trading post. . These cover the administrative decisions made, letters sent and received, visits to and from the Factory An East India Company trading post. , trade activities, inland and offshore military operations, in addition to miscellaneous reports of other political and commercial events taking place in the region.

Apart from their administrative nature, the diaries stand out as an extensive and under-utilised source for the study of commercial activities in eighteenth-century Persia and the Gulf. These can be glimpsed through the records they preserve of the activities of the British, Dutch, and French trading companies, as well as of local Persian, Arab, and occasionally Armenian merchants in the region. Such records help trace the history of foreign powers’ interest in the region, and their encounters with and among local authorities.

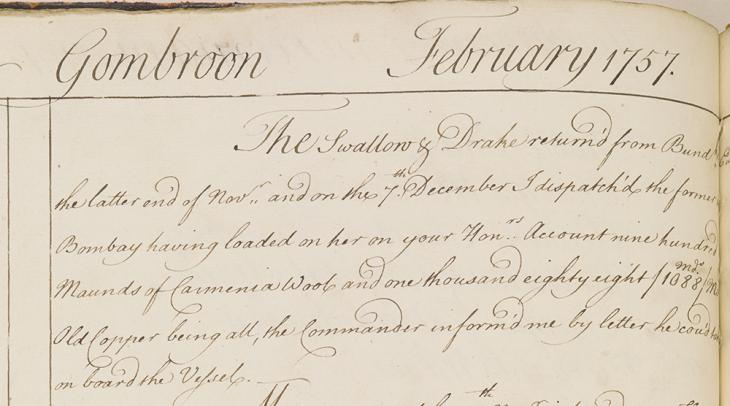

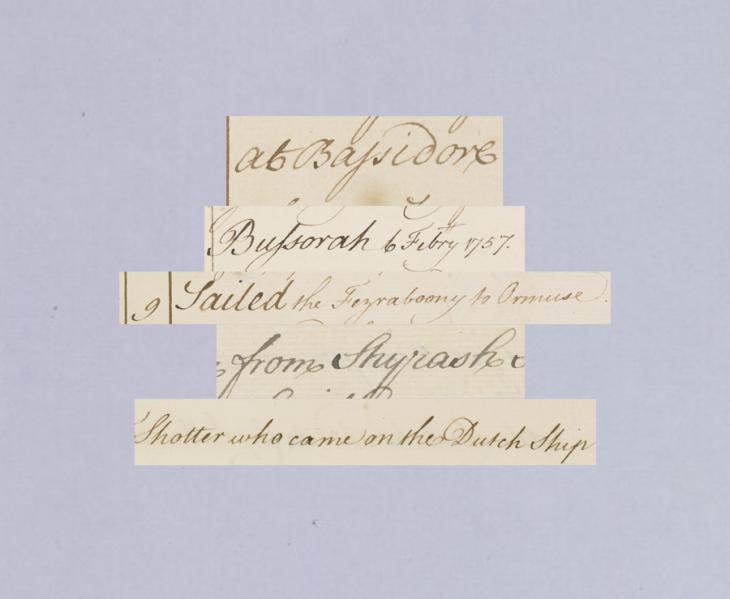

The records of commercial activities also reveal some remarkable information about the movement of foreign and local ships and the busy ports at the time. Examples of the names of ships that appear regularly in the records are: the Drake, the Britannia, the Queen Carolina, the Swallow, the Fayz Rabbani, and the Warwick. Among the many ports the ships sailed to and from are: Bandar-e ‘Abbas, Bombay [Mumbai], Basra, Bandar-e-Rig, Surat, Bandar-e Charak, Mocha, Muscat, and Bushehr.

The commercial aspect is also preserved in the records of traded commodities, mainly woollen goods, rice, grain, sugar, copper, spices, and coffee. In addition, there are numerous references to the names of Persian currencies used at the time, and their exchange rates in Indian rupees Indian silver coin also widely used in the Persian Gulf. , which makes for an important source on exchange rates in the eighteenth century.

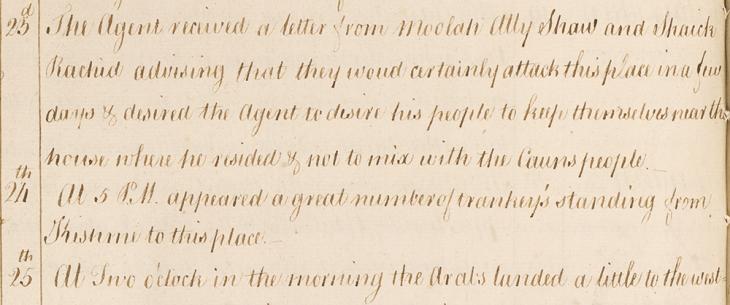

The highlights of the diaries, however, are the records they contain of the state of affairs and the never-ending inland and offshore military operations. These introduce readers to the names of prominent military generals, regional governors, and influential tribes involved in such operations. These include but are not limited to: Shah Tahmasp II, Nadir Shah Afshar, Ahmad Shah Afghan Durrani, Shahrukh Mirza Afshar, Karim Khan Zand, Azad Khan Ghilza’i, Nāṣir Khan Al Madhkur, Shaikh Ahmad Madani, Shaikh Hatim bin Jubarah al-Naṣūrī, Shaikhs Rāshid and Rahmah al-Qasimi and the tribes of Jubarah, the Banu Mu‘in, and the Al ‘Ali.

Indeed a large number of towns and provinces are also mentioned in the diaries as part of the accounts of the military operations. These include Bandar-e ‘Abbas, Isfahan, Qazvin, Yazd, Tabriz, Khorasan, Mashhad, Mazandaran, Shiraz, and Qishm Island.

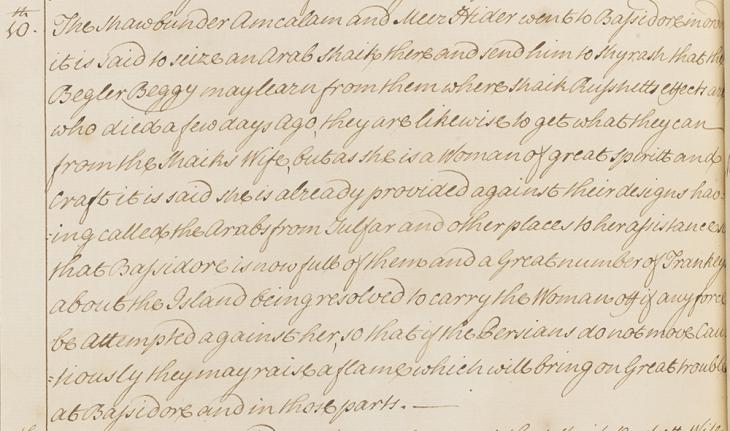

Further, the diaries preserve some occasional, yet fascinating records of weddings, deaths, celebrations, personal disputes, etc. An example of these is the news of Mulla ‘Ali Shah, Governor of Gombroon, marrying his daughter to the Shaikh of Julfar. Another interesting example is the dispute between some Persian officials trying to seize the effects of the late Shaikh Rāshid of Basaʻidu, and the reaction of his widow, supported by the Arabs of Julfar. These indeed stand as examples of the richness of the diaries as invaluable primary source material on eighteenth-century Persia and the Gulf.

One last feature to explore is the rather amusing way non-English names/terms appear in the diaries. It is most likely that the Factory’s employees tried to transcribe certain words the way they heard them locally. This has resulted in many of these words having multiple spellings throughout the diaries. Examples of these include: Shayrash/Shyrass/Schyrash [Shiraz], Bussorah/Bussarah/Bossarah [Basra], Bassidow/Bassidor/Bassidore [Basaʻidu], Shaw Thomas [Shah Tahmasp], shottor/shotter [shātir], Aphgoon/augwuan/Affghoon [Afghan], and the ship Fouzerabooni/Fuzeraboony/Fezraboony [Fayz Rabbānī]. Indeed, some of these terms can prove difficult to work out without prior knowledge of Arabic or Persian.

Conclusion

With the variety of topics they cover, the surviving Gombroon Diaries stand out as primary source material on the commercial, political, and military history of the region. It is without doubt, however, that the records the Diaries preserve of the politico-military events outnumber those of the commercial activities. This surely suggests that the existence of the EIC in the region cannot be interpreted as being merely out of commercial interest. In fact, if anything, these fascinating diaries demonstrate the role the EIC played in the course of the events in Persia and the Gulf region from the eighteenth century onward.