Overview

The extant Andalusian sundials correspond to the horizontal type (the curves traced by the solar shadow in the winter and summer solstices are arcs of a hyperbola, while the shadow in the equinoxes traces a straight line). These instruments also contain curves corresponding to the hour of the midday (ẓuhr) and afternoon prayers (‘aṣr). Written sources also describe equatorial dials, wrongly interpreted as horizontal ones. We have little information about medieval instruments built in the Maghrib although we are aware of an important tradition of instruments of this kind in Tunis from the seventeenth century onwards. In this context it is quite surprising to discover an extremely mature and brilliant description of some eight types of sundial in Ibn al-Raqqām’s work.

The Author

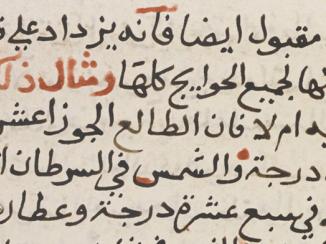

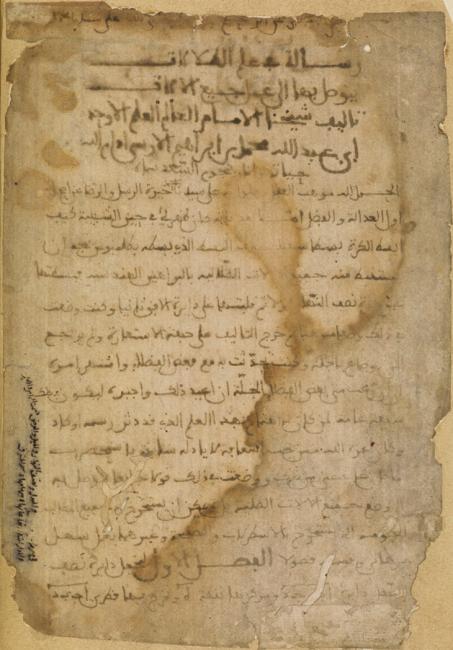

Abū ‘Abd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Ibrāhīm ibn ‘Alī ibn Aḥmad (Muḥammad?) ibn Yūsuf al-Andalusī al-Tūnisī al-Awsī , known as Ibn al-Raqqām,“belonged to the people of Murcia” (min ahl Mursiyah) and died in Granada on 21st Ṣafar 715/26th May 1315 at an advanced age. He lived in Tunis and Bijāyah (Béjaïa) and migrated from Bijāyah to Granada during the reign of the Naṣrid sultan Muḥammad II (reg. 671/1273–701/1302), probably after 687/1288-89. He was a polymath who wrote on many different topics, although his most important works deal with astronomy. Among them we find his three sets of astronomical tables (zījes), compiled in Bijāyah and Tunis, which are re-elaborations of the unfinished zīj of Ibn Isḥāq (fl. at Tunis and Marrakech c. 1193–1222). He also wrote a treatise on sundials, the Risālah fī ‘ilm al-ẓilāl (On the Science of Shadows), a science also known as gnomonics.

The Risālah fī ‘ilm al-ẓilāl

According to Ibn al-Raqqām, a simple method for the projection of the sphere occurred to him during his youth, and he wrote his book on this subject while he was still a young man. But somebody borrowed his manuscript and never returned it. Later, some other scholars from Ifrīqiyah asked him to write the book again. All this suggests that the extant book was written in the latter half of the thirteenth century, probably in Tunis or Bijāyah.

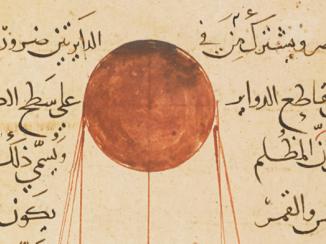

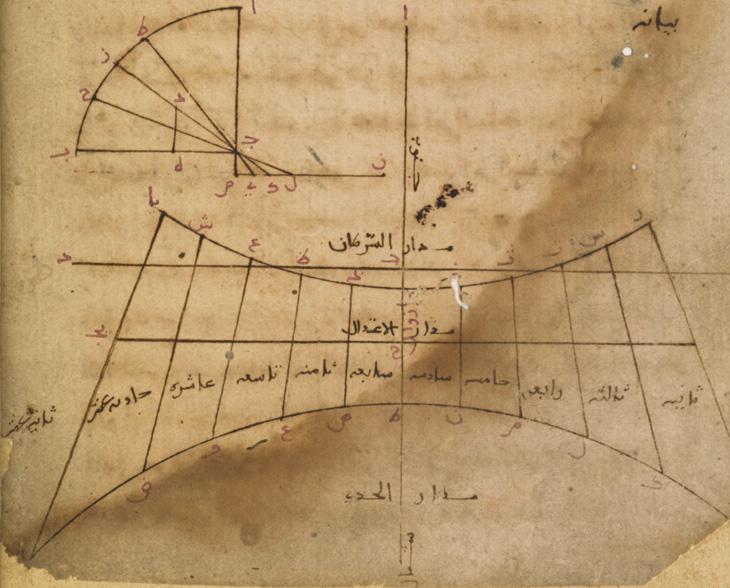

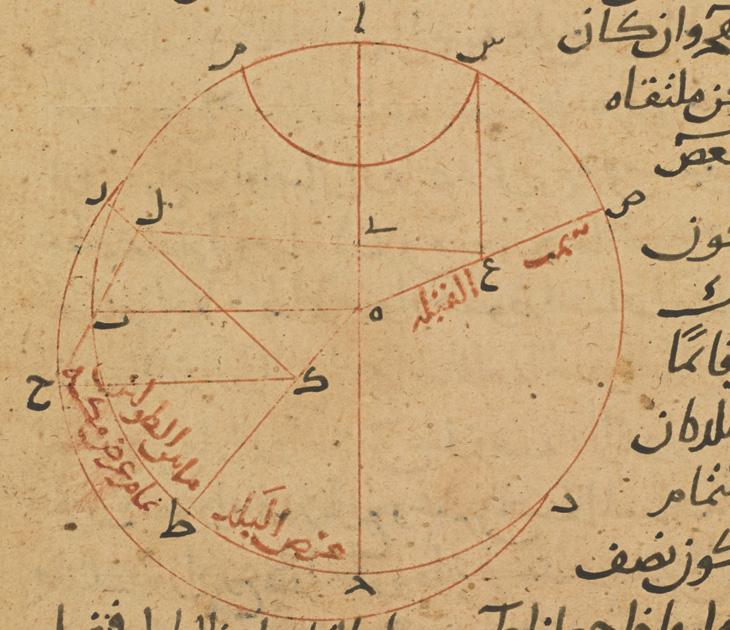

Ibn al-Raqqām’s technique for the projection of the sphere was different from the one invented by Ptolemy (probably the stereographical projection used in astrolabes and similar instruments described for the first time in Ptolemy’s Planisphere). Surprisingly, Ibn al-Raqqām’s procedure corresponds to the analemma, an old Greek technique for representing on a plane some elements of the sphere in order to find certain arcs and angles which determine a point in space, while avoiding the use of trigonometry. Ibn al-Raqqām could not have known Ptolemy’s treatise on this topic, the Analemma, since it had not been translated into Arabic. Although analemmatic techniques had often been used by Eastern Arab scientists for various purposes, but mainly for the construction of sundials, Ibn al-Raqqām appears to have been the first to use this technique in al-Andalus or the Maghrib.

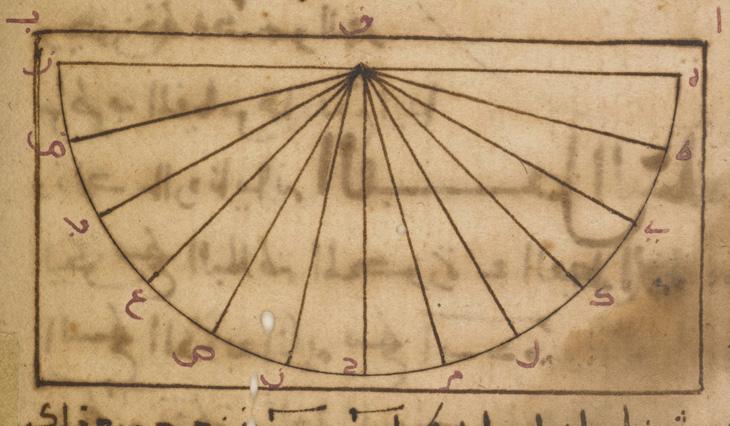

In his On the Science of Shadows, Ibn al-Raqqām describes eight different types of sundials. Among them we find the standard horizontal sundial, the vertical sundial (the plane of which is parallel to the prime verticalthe vertical circle passing through the East and West points of the horizon), and the gnomon is placed on the meridian line), the equatorial sundial (the plane of which is parallel to that of the equator, and the perpendicular gnomon points to the North Pole), the scaphe (a sundial traced on the inner surface of a hollow hemisphere whose pole is the basis of the gnomon the end of which coincides with the centre of the sphere) and the portable sundial with a magnetic needle which allows a correct orientation of the instrument. This is, in fact, one of the earliest secure references to the magnetic compass in Western Islam.

Besides this, Ibn al-Raqqām posed and solved the problems of the transformation of solar quadrants: given a sundial built for a particular latitude, how could one build another sundial of a different type for the same latitude? He also explained the procedure for tracing on the sundial other lines (projections of the declination parallels corresponding to the zodiacal signs, and those of the almucantars or altitude circles) which allowed the instrument to perform functions normally carried out with astrolabes or similar computing devices. Following the standard tradition, Ibn al-Raqqām explained in detail how to trace the curves corresponding to the prayer hours and dealt with the determination of the azimuth of the qiblah for which he used an analemma similar to the one described by Ḥabash al-Ḥāsib in the ninth century, and by al-Bīrūnī in the eleventh century in his al-Qānūn al-Mas‘ūdī.

Conclusions

Islamic astronomers have always been interested in building sundials not only because of their use in everyday life, but also for the exact determination of prayer times. An important scientific tradition which studied the techniques for the construction of such instruments had appeared in the East since the as early as the ninth century, but there were no similar developments in the Maghrib until the appearance of Ibn al-Raqqām’s book, written in the latter half of the thirteenth century, a historical period traditionally considered to be a period of decay.