Overview

The art of letter dispatching has taken many forms over the centuries. From a leather scroll to a simple piece of paper and an envelope, each letter has a unique story behind its preparation, reflecting the period of its creation, and the status of its sender and receiver. A kharita An important letter usually sent in an elaborate textile pouch, dispatched as part of the royal or diplomatic correspondence of rulers and elites. is one example of such a letter with its own story. The term applies to a type of letter that was usually sent in an elaborate textile pouch, and for centuries was dispatched as part of the royal correspondence of Muslim rulers. In Arabic, the term kharita An important letter usually sent in an elaborate textile pouch, dispatched as part of the royal or diplomatic correspondence of rulers and elites. (pl. kharaʾit and khurut) means a pouch or bag made of leather, silk, or other material; it also means a map. This article examines one particular kharita An important letter usually sent in an elaborate textile pouch, dispatched as part of the royal or diplomatic correspondence of rulers and elites. that is part of the Curzon Papers, in the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. and Private Papers Documents collected in a private capacity. collection at the British Library, which has been digitised for the Qatar Digital Library.

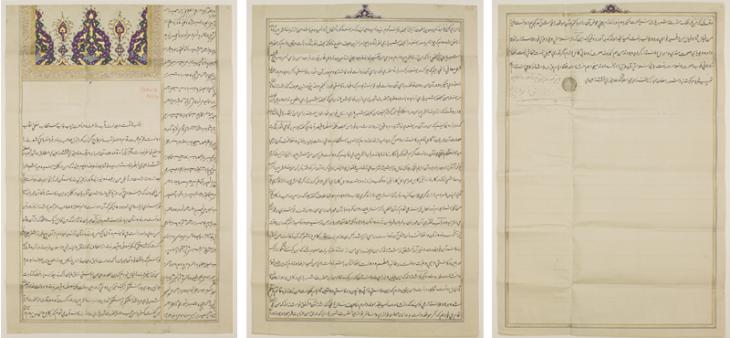

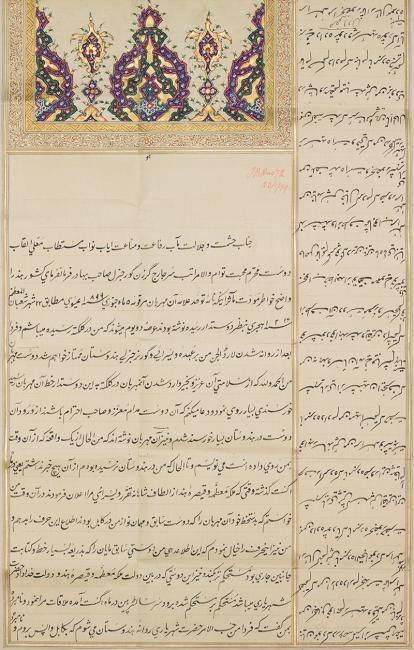

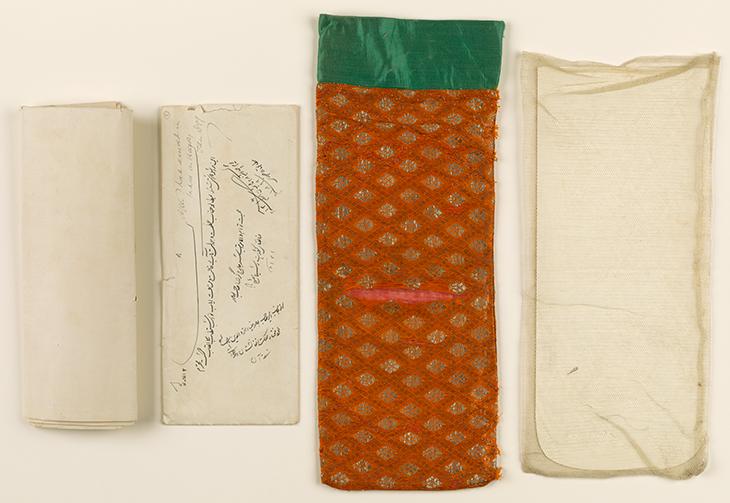

This kharita An important letter usually sent in an elaborate textile pouch, dispatched as part of the royal or diplomatic correspondence of rulers and elites. is an official letter sent by the Amir of Afghanistan Abdul Rahman Khan Barakza’i (r.1880-1901 CE), to Lord George Nathaniel Curzon, Viceroy of India (in office 1899-1905 CE). It contains a three-page illustrated ceremonial letter, a paper envelope, a silk pouch, and a bobbinet cotton pouch. Rather than describing the contents of the letter, this article will closely examine the items that form the kharita An important letter usually sent in an elaborate textile pouch, dispatched as part of the royal or diplomatic correspondence of rulers and elites. and describe the way in which they were put together to create a piece of late nineteenth-century royal art.

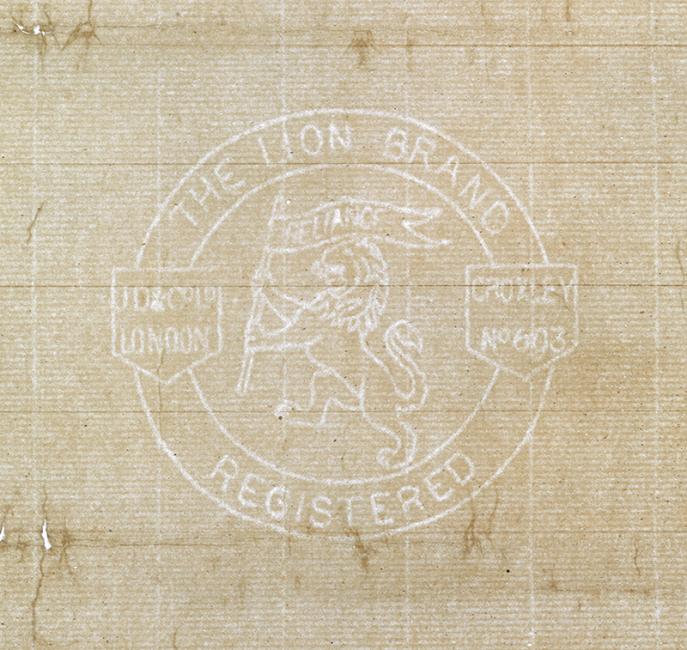

The Paper

The letter is written in Persian on large sheets of watermarked paper. The paper was most likely purchased through the East India Company, and stocked as stationery at the chancellery (dar al-insha’) of the palace of Amir Abdul Rahman. A close examination of the watermark reveals that it is circular and contains an image of a lion holding a flag with the motto ‘Reliance’. To its left, the line reads: ‘JD & Co Ld/London.’ To the right it reads: ‘Croxley/No 693.’ This indicates that the stock of paper was purchased at John Dickinson, a London-based nineteenth-century stationery firm, and printed at the firm’s Croxley Mill (No. 693).

Preparing page one: Dividing, Illuminating, Lining, and Writing

From its lay out, the first page seems to be of particular importance. It is divided into three parts: the top with floral illumination, the middle with the main text, and the right-hand margin. The explanation for such an arrangement has to do with dimensions, since the paper (605x415mm) is larger than the floral illumination template (140x265mm). Therefore, the scribe and/or illuminator had to divide the first page to accommodate the illumination template within the dimensions of the paper.

With the main body of text positioned directly underneath the floral illumination, the page was left with a margin on the right-hand side. The common practice in such a situation was either to fill the margin with writing or to illuminate it. Here, the scribe used it for further text. Upon finishing the main body, the scribe turned the page by a hundred and eighty degrees (without turning it over) and continued writing slantwise. This step was taken purely to ensure that the writing did not all go in one direction, which would likely have confused the reader, especially given that Persian is written from right to left. Before the writing process took place, the page had already been faintly lined throughout both the main body and the margin.

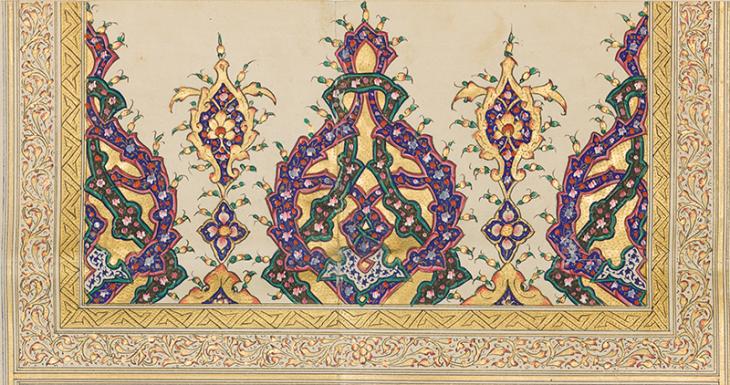

The floral illumination presents a crown-like shape (taj) in the middle and two half-crowns on the sides. The crowns are surrounded by two half-square frames; one has a geometric illumination and the other a floral design. The shape clearly provides a majestic association with the sender of the letter, Amir Abdul Rahman. Once the illumination template was drawn, the processes of gilding (tadhhib) and colouring could begin. Gold leaves would usually have been used in tadhhib, while henna, saffron, pomegranate, rice, and precious stones were among the materials used to extract colours. Apart from the obvious gold leaves used here, it is difficult to identify the other materials used to create the colours. These are dark green, a light shade of black, two gradations of pink, ivory white, purplish blue, and a light shade of red. Underneath the illuminated frame, the phrase ‘Ya Hu/Ya Huwa’ (يا هوْ/ يا هوَ) is neatly inscribed. In many ways, one could consider the phrase as an essential part of the illumination regardless of whether it was placed underneath or within the frame at the top. The phrase comes from Arabic and it is of praise to God. It is also possible to suggest that it indicates the scribe and/or the illuminator is putting his trust in God before proceeding with the writing.

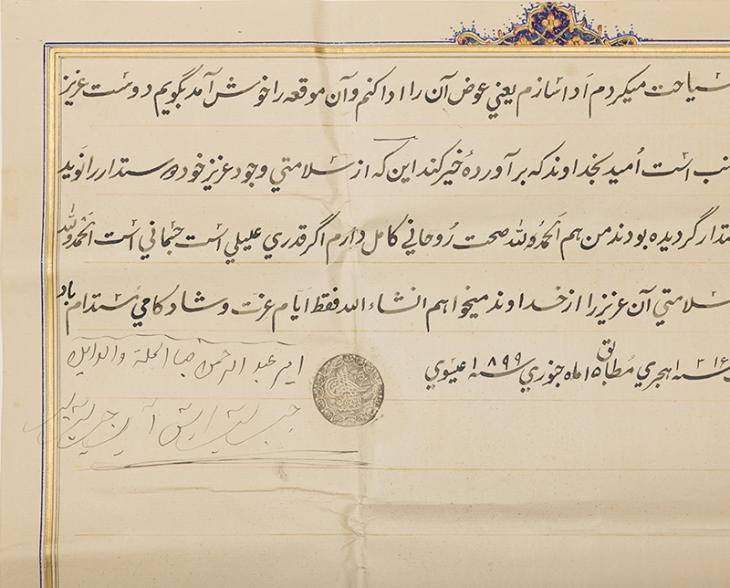

Pages Two and Three

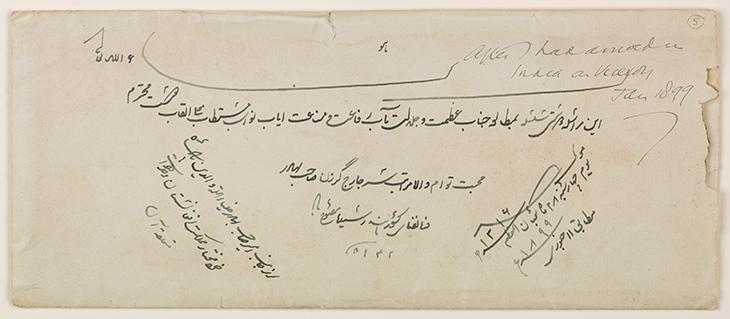

The second and third pages are simpler with respect to illumination. Each page has a golden frame with a small floral design on top, and has been faintly lined for writing. Once the scribe had completed the writing process, he added the date, Ramadan 1316 AH/ January 1899 CE. The Amir then affixed his seal and signature after the body of text on the left-hand side. It is important to emphasise that the processes of illuminating and writing may have involved the collaboration of a number of scribes and illuminators, but it is difficult to determine precisely how many individuals were involved in creating this piece of art.

The Pouches

The three-page letter was folded and inserted into an open top paper envelope. Once sealed with wax, the envelope was placed inside a silk pouch, which was in turn put into a bobbinet cotton pouch. The dimensions of these two pouches indicate that the cotton pouch was used as an outer protective cover for the silk.

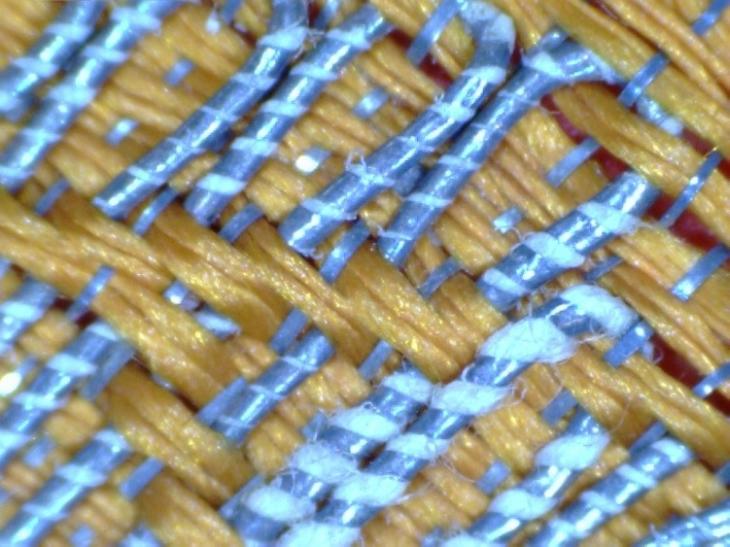

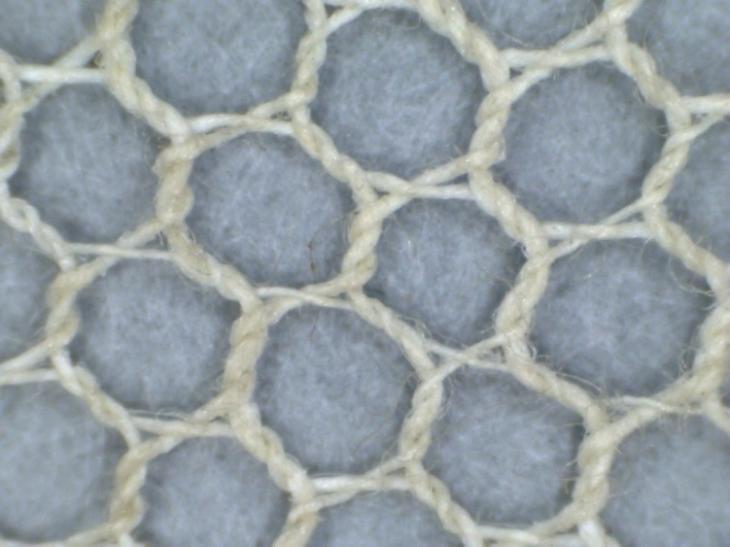

The silk pouch is made from orange silk in a diamond twill weave, with twisted silver and silver “ribbon” wefts. It is hand-stitched along one short and one long edge. The opening is edged with a satin weave of emerald green silk that is lined with an open weave tabby of bright pink cotton. The cotton pouch is a natural-coloured two-twist bobbinet that is hand-stitched along one short and one long edge. A visible slit in the middle indicates that both pouches were folded in half.

With the letter inside the envelope, the envelope inside the silk pouch, and the silk inside the bobbinet cotton pouch, the kharita An important letter usually sent in an elaborate textile pouch, dispatched as part of the royal or diplomatic correspondence of rulers and elites. was ready to be dispatched.

Beyond Politics to Art

Considering the dictionary definition of kharita An important letter usually sent in an elaborate textile pouch, dispatched as part of the royal or diplomatic correspondence of rulers and elites. , one might assume that the term can only be used to describe the pouches, or even just the silk pouch. However, the pouch would have little significance if it were sent by itself. Therefore, we can reasonably assume that the term kharita An important letter usually sent in an elaborate textile pouch, dispatched as part of the royal or diplomatic correspondence of rulers and elites. would technically apply to all the items put together, namely the three-page letter, the envelope, and both pouches. This study takes us beyond identifying this kharita An important letter usually sent in an elaborate textile pouch, dispatched as part of the royal or diplomatic correspondence of rulers and elites. as political correspondence between two paramount powers, and instead shows the amount of labour that went into its preparation, from the purchase of the paper to the dispatch of the letter. This article brings together the elements that make this kharita An important letter usually sent in an elaborate textile pouch, dispatched as part of the royal or diplomatic correspondence of rulers and elites. unique as an item of royal art from nineteenth-century Afghanistan.

FURTHER READING

Ula Zeir, ‘ Kharita An important letter usually sent in an elaborate textile pouch, dispatched as part of the royal or diplomatic correspondence of rulers and elites. : the royal art of letter dispatching’, Afghanistan, 2.1 (2019), 141-152