Overview

The involvement of Prince Najaf Ali Khan Zand of Persia [Iran] in the death of two sepoys Term used in English to refer to an Indian infantryman. Carries some derogatory connotations as sometimes used as a means of othering and emphasising race, colour, origins, or rank. at the port of Panvel in north-western India sparked intense deliberations amongst members of the Government of Bombay’s highest authority: the Council. With matters complicated by the Prince’s rank and his relationship with the Government, how would they proceed in such a delicate situation?

A New Dynasty in Persia

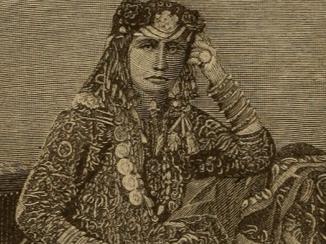

Prince Najaf was born in the late eighteenth century into the Zand dynasty, which had ruled most of Persia since 1751. Following the death of its founder Karim Khan Zand in 1779, the dynasty was fractured by in-fighting and by the threat of rivals in northern Persia. The Zands were overthrown when Prince Najaf’s older brother, Lotf-Ali Khan, was defeated by Agha Muhammad Khan Qajar in 1794.

In the early nineteenth century, Prince Najaf departed from Persia and made his way to Bombay [Mumbai]. He was given refuge by the East India Company’s Government of Bombay From c. 1668-1858, the East India Company’s administration in the city of Bombay [Mumbai] and western India. From 1858-1947, a subdivision of the British Raj. It was responsible for British relations with the Gulf and Red Sea regions. , which provided him with a house and a pension of 400 rupees Indian silver coin also widely used in the Persian Gulf. per month.

A fatal dispute

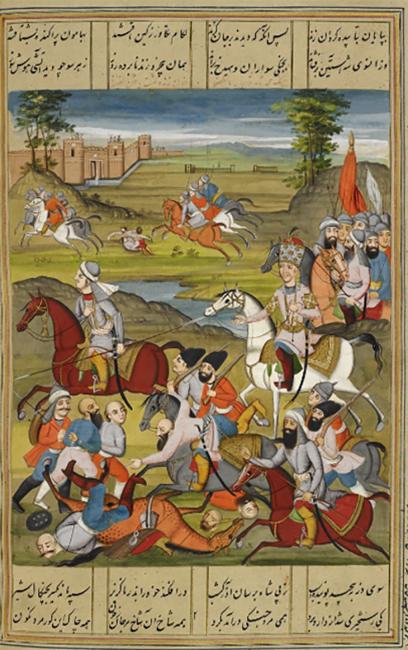

The Prince continued to live in Bombay, enjoying the respect shown to him as a member of the former ruling house of Persia, until things changed in 1828 during a trip to the port of Panvel, east of Bombay. A group of Custom House sepoys Term used in English to refer to an Indian infantryman. Carries some derogatory connotations as sometimes used as a means of othering and emphasising race, colour, origins, or rank. were instructed by their supervisor to collect unpaid duties owed by the Prince (in this context, it is presumed that the term sepoy Term used in English to refer to an Indian infantryman. Carries some derogatory connotations as sometimes used as a means of othering and emphasising race, colour, origins, or rank. is used to refer to military men). When they approached his entourage, the interaction turned violent. During the disturbance, Prince Najaf drew his pistol and fired, killing two of the sepoys Term used in English to refer to an Indian infantryman. Carries some derogatory connotations as sometimes used as a means of othering and emphasising race, colour, origins, or rank. .

The Prince was arrested and the Zillah [Zila’ or small district] Court passed the case up to the Criminal Court in the Northern Concan [Konkan]. However, the sensitivity of the case resulted in its being referred to the Council. Should Prince Najaf be tried according to the regular process, or did his rank merit a special procedure?

Disagreements from the Outset

Extracts from the Government of Bombay From c. 1668-1858, the East India Company’s administration in the city of Bombay [Mumbai] and western India. From 1858-1947, a subdivision of the British Raj. It was responsible for British relations with the Gulf and Red Sea regions. Political and Judicial Consultations, preserved in the IOR/F/4 records series, reveal that members of the Council could not agree on a course of action. They met on 25 February 1829 to discuss the case for the first time.

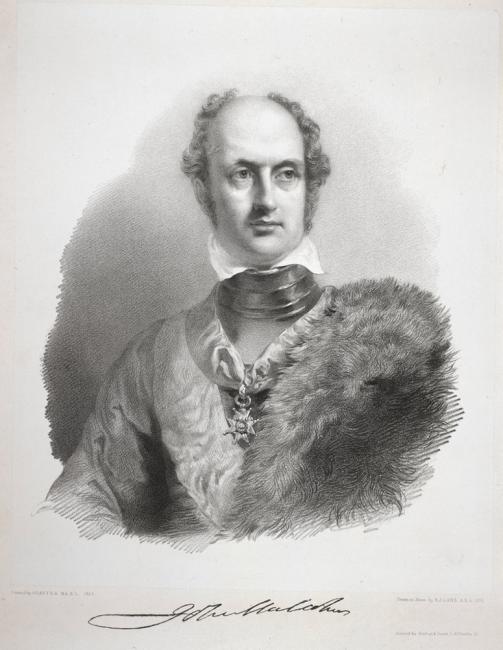

The Governor, Sir John Malcolm, was against trying the Prince in court as he felt this would be too detrimental to Anglo-Persian relations. Due to the Prince’s rank, Malcolm was convinced that ‘nothing could more shock feelings of the Persians nor make a worse impression in Persia than this person’s being tried in a Zillah Court, like a common malefactor’ (IOR/F/4/1266/50907, f. 289r). He was not opposed to punishing the Prince if necessary, but argued that the mode of punishment should be tempered by political considerations.

Conversely, Council member John Romer argued that they should leave the case to the relevant tribunals. He warned that the ‘ends of public justice demand this proceeding’ (IOR/F/4/1266/50907, f. 290v), and that no other authority could deliver such justice. While acknowledging the political difficulties of the case, he argued that these would be further complicated by any departure from the established legal procedures.

The Council agreed that they needed more information to make a decision. Accordingly, the Criminal Judge in the Northern Concan was asked to conduct preliminary investigations, and send the Council the collected depositions for consultation.

A Stark Warning

The Council met again on 29 April 1829, having reviewed the evidence, but neither Malcolm nor Romer had moved from their respective positions.

In a lengthy minute, Malcolm declares his conviction that the Prince had only fired his pistol after being physically assaulted by the sepoys Term used in English to refer to an Indian infantryman. Carries some derogatory connotations as sometimes used as a means of othering and emphasising race, colour, origins, or rank. . Citing Prince Najaf’s self-defence, he states that the Government could now justify ‘bending’ the rules of law in order to protect him from a trial. He goes on to set out examples of other European governments making similar exceptions in the interests of national security, and reiterates that the ruling family of Persia would be incredibly offended by the British ‘degrading’ the Prince with a trial. He also cautions that the tribes of southern Persia, from amongst whom the Zand family originated, would view the British as having breached the laws of hospitality and friendship. The tribes might even take retaliatory action against the British with violence and theft, he warns.

Yet, as Malcolm continues, ‘…these effects would be small in comparison to the political evils that might result from this proceeding’ (IOR/F/4/1266/50907, ff. 331r-331v).

Malcolm’s Bigger Picture

During the discussions, Malcolm revealed that Prince Najaf had in 1808 asked the Company to assist him in overthrowing the Qajars. Despite ultimately rejecting his request, the Governor-General in Bengal had noted that supporting Prince Najaf would weaken the position of the Qajar ruler – Fatḥ-Ali Shah (r. 1797-1834) – who had been drawing up treaties with the French. These negotiations had alarmed the Company, who feared that a Perso-French alliance would provide Napoleonic France with an invasion route to British India.

Here, Malcolm voices his concern that if Anglo-Russian relations were to deteriorate, the Russians might try to persuade Persia to allow them access to India. He argues that the best possible defence would be to ‘excite’ the tribes in southern Persia to rebel against the Qajars, thereby creating a belt of unrest to deter any potential attacks on India’s northern border (IOR/F/4/1266/50907, f. 331v). While Malcolm admits that this general scenario is unlikely, he contends that a public trial of Prince Najaf would inadvertently weaken Britain’s defences in northern India.

Romer nevertheless still concluded that Prince Najaf had fired first, and that the evidence was therefore sufficient to charge him with murder. Dismissing Malcolm’s reservations, he stresses that the Government must always prioritise the principles of law and justice over preferential treatment.

![Extract of Minute by John Romer, 25 April 1829, arguing that ‘I do not think that any political considerations [justify] withdrawing him [Prince Najaf] from the hands of justice.’ IOR/F/4/1266/50907, ff. 335v-336r](https://www.qdl.qa/sites/default/files/styles/standard_content_image/public/ior_f_4_1266_50907_0119.jpg?itok=9mwwcqtA)

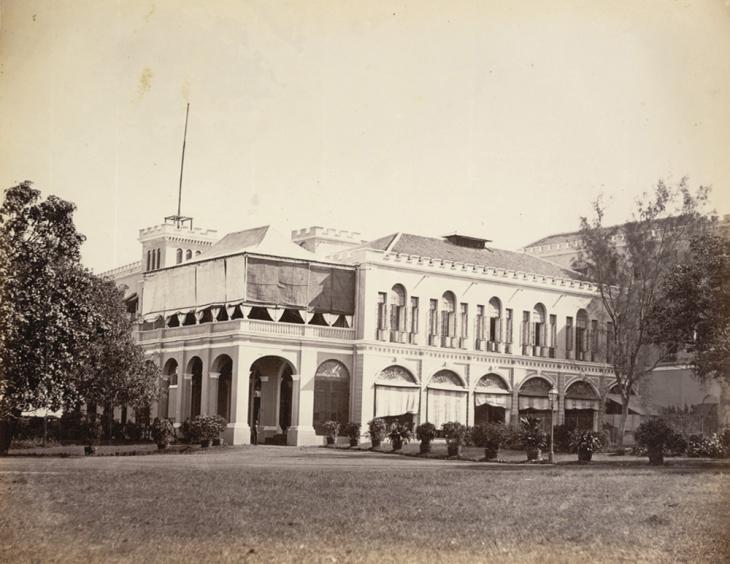

Prison Fit for a Prince

Ultimately, however, the Governor-General in Bengal sided with Malcolm, outranking any objections from Romer. Consequently, the Prince was given preferential treatment and managed to avoid a trial. He was kept as a state prisoner at the Company’s fort at Tannah, where his living quarters consisted of three rooms, and his private servants continued to wait on him. The Government of Bombay From c. 1668-1858, the East India Company’s administration in the city of Bombay [Mumbai] and western India. From 1858-1947, a subdivision of the British Raj. It was responsible for British relations with the Gulf and Red Sea regions. decided the best course of action was to send the Prince and his family to Bussorah [Basra], where he would be able to continue living as a free man. He was warned that if he ever returned to Bombay, he would be put on trial for the murders of the sepoys Term used in English to refer to an Indian infantryman. Carries some derogatory connotations as sometimes used as a means of othering and emphasising race, colour, origins, or rank. .

Conclusion

Despite negotiating several treaties with the Qajar rulers of Persia throughout the early nineteenth century, the Government of Bombay From c. 1668-1858, the East India Company’s administration in the city of Bombay [Mumbai] and western India. From 1858-1947, a subdivision of the British Raj. It was responsible for British relations with the Gulf and Red Sea regions. had also cultivated a relationship with a member of the former regime. The trial, or lack thereof, of Prince Najaf serves to illustrate that even murder was not cause enough for the Government to risk the potential returns on its political investments.