Overview

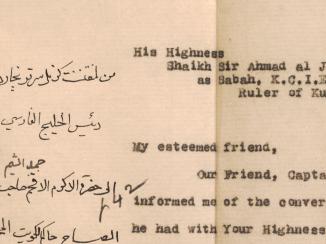

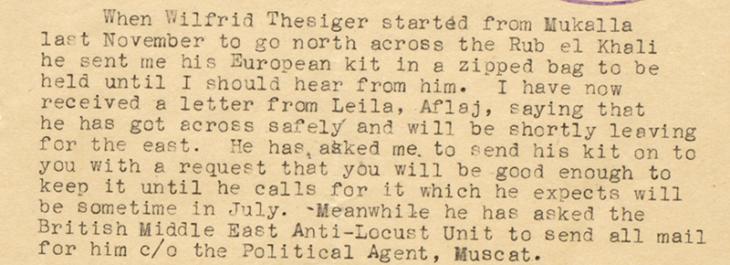

At the end of April 1948, the Political Agency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, headed by an agent. at Bahrain received a kit bag accompanied by a letter from Edwin Chapman-Andrews, the British Minister at Cairo.

The letter relayed the news that Wilfred Thesiger, the British explorer and writer The lowest of the four classes into which East India Company civil servants were divided. A Writer’s duties originally consisted mostly of copying documents and book-keeping. , had successfully crossed the Rub‘ al-Khālī, (Empty Quarter), a large expanse of sand desert in the south of the Arabian Peninsula, and requested that his ‘European kit’ be kept at the Agency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, headed by an agent. ‘until he calls for it’. An insignificant event in the day-to-day business of the Agency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, headed by an agent. , it would seem, but it can now be read as a clear illustration of the close relationship between individual exploration and empire.

18th century: A Little-Known Land

Before the eighteenth-century, few Europeans had journeyed far into the interior of the Arabian Peninsula. Members of the indigenous Arab population, of course, had done so a great deal, but the literature written in Arabic tended to concentrate on caravan routes and pilgrimage roads. Ibn Battutah is a famous example; Ibn al-Mujawir, a lesser-known one.

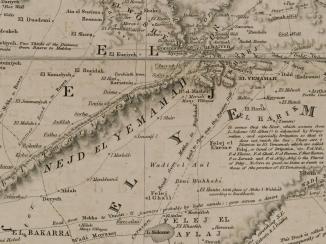

From the late 1700s onwards, European knowledge of the geography of Arabia expanded as more explorative journeys were made. Often carried out in the name of science – the Danish expedition of 1762, led by the explorer Carsten Niebuhr, was an early example – they were frequently funded and facilitated by imperial governments. The close relationship between science and the quest for knowledge on the one hand, and empire-building and political control on the other, is well-documented in the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. Records.

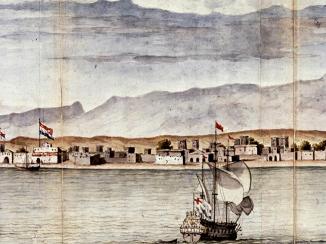

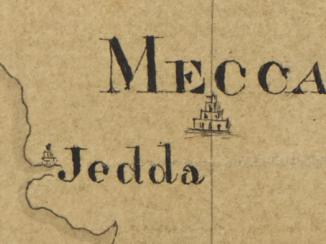

In 1819, George Sadleir became the first European to cross the peninsula. He did so as part of a mission for his East India Company employers; extracts from his notes on the journey can be found in the Bushire record. Following Johann Ludwig Burckhardt’s visit to the holy cities of Mecca and Medina in 1815, explorations of the region increased.

19th century: The Knowledge-Empire Spreads

The nineteenth-century witnessed a flowering of geographical societies in Europe. These organisations began to amass great stores of knowledge on the geography, flora, and fauna of the world, often gleaned from the observations of intrepid travellers. The most influential men within these societies were often active or retired members of government.

Following the Napoleonic Wars, Britain, in particular, had a vested interest in advancing its geographic knowledge of the Middle East. In competition with France and desirous of expanding and protecting its strategic interests, particularly in connection to India, Britain was quick to recognise the political and military value of such knowledge.

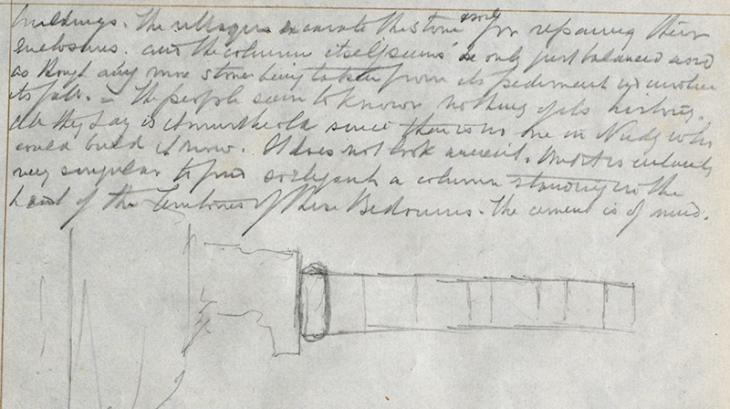

Charles Doughty, Richard Burton, William Palgrave, Lady Anne Blunt, and Lewis Pelly all made pioneering journeys into the interior of Arabia in the latter half of the nineteenth-century. Many of them were closely connected to the British military or government, if not directly employed by them. As well as publishing accounts of their journeys, most would have presented detailed, more ‘scientific’ notes to one of the learned societies, most often the Royal Geographic Society (RGS). The journal of Lewis Pelly, written during a journey to Riyadh, is one such example.

20th century: WWI and Empire

The twentieth century brought a further increase in European exploration of Arabia and a closer, more explicit relationship between these travellers, the learned societies and the British Empire. The First World War saw active participation by the RGS in military planning. It is no coincidence that one of T. E. Lawrence’s mentors was David Hogarth, a prominent member of the RGS Council.

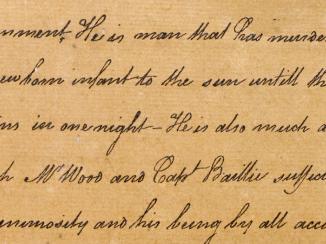

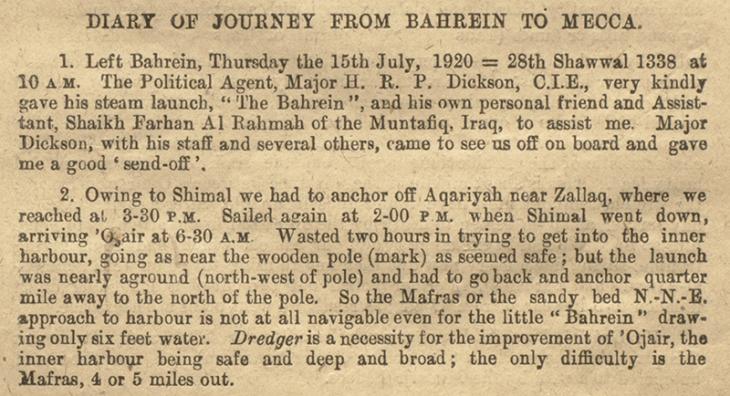

Throughout the first half of the century many more journeys were made. Gertrude Bell, Arthur Wavell, Robert Cheesman and William Shakespear made well-known trips into parts of Arabia little-explored by Europeans. But other less-known explorations were made by employees of the British Imperial and Indian Governments, such as Harold Dickson, Siddiq Hassan, Charles de Gaury and Farhān al-Raḥmān. Their accounts take the form of letters, reports, and diaries, some of which were never published.

Bertram Thomas became the first European to cross the Rub‘ al-Khālī, in 1930. St John Philby followed him shortly after. Philby, maverick in his ways, became a pariah and the British authorities endeavoured to block his later attempts to travel in the region. The third man to cross the Rub‘ al-Khālī, Thesiger, described his work for the government as providing him with the ‘golden key to Arabia’. It also delivered his clothes to his destination for him.

These explorers would never have been able to achieve what they did without the knowledge and guidance of the Arabs who lived in the places they visited; their names have mostly been forgotten. But equally, without the financial and logistical support of imperial governments, these explorations would not have occurred. Impressive as they are, European explorers’ legacies will always be compromised by their involvement with the empires that supported and promoted their acquisition of knowledge, and what that knowledge was used for.