Overview

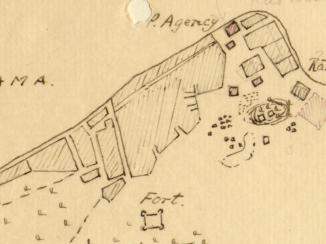

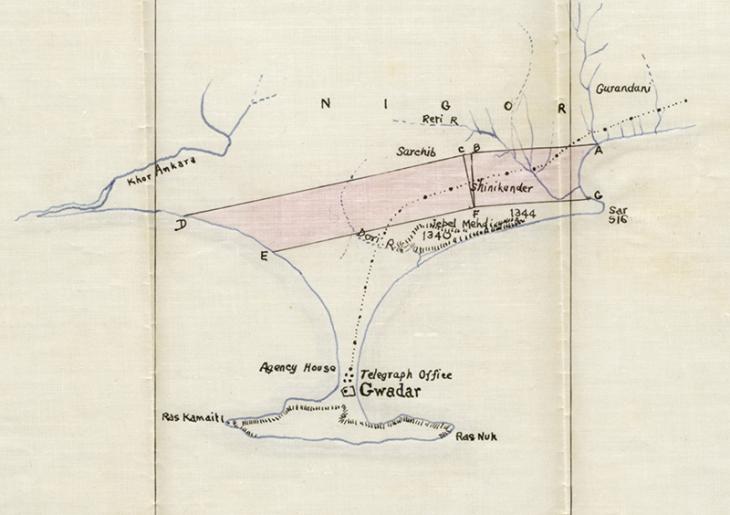

Located on the Makran Coast of Baluchistan, the port of Gwadar first came into Omani possession in 1784 when its ruler, Nasir Khan of Kalat, conferred the area on Sulṭān bin Aḥmad. An unsuccessful pretender to the throne of Oman at the time, Sulṭān bin Aḥmad began using Gwadar as a base for raids on the Arabian coast opposite, and after obtaining supreme power in his homeland in 1792, he completed the annexation of Gwadar to Oman.

For most of its existence, Gwadar remained a small community with an economy based on fishing. In 1863, the Khan of Kalat made an attempt to reincorporate Gwadar within his own territory, or Khanate, and to end the anomaly of this enclave of Omani territory on the Baluchistan coast. But the British refused to support his claim. There were further proposals between 1895 and 1904 both by the Khan and the Government of India to purchase Gwadar from the Omanis, but no decision was reached.

Oil and Rebels

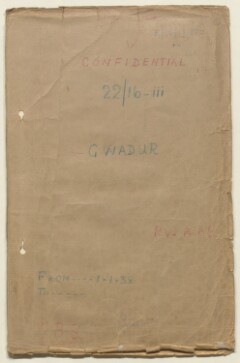

The dispute continued during the twentieth century. British administrative files contain many papers relating to the question of sovereignty and demarcation of boundaries between the two territories. The importance of the dispute increased in 1914 both for Kalat and the British, when the Burmah Oil Company began to investigate the possibility that oil existed within the boundaries of Gwadar. This gave the area a further potential economic value for all interested parties. The British thought initially that the Sultan, Taymūr bin Fayṣal, would be ‘very reluctant to give up Gwadar’, but in the event the Sultan was reported as stating in a telegram of 19 April that he would ‘give the British Government Gwadar or Dhurfar [Dhofar]’ in return for military help against rebels.

Political Bargaining with a Gulf Ruler

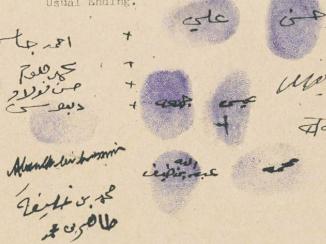

The issue resurfaced in 1939 in the course of discussions between the British Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. in Muscat, Captain Tom Hickinbotham, and the then Sultan, Sa‘īd bin Taymūr. The Sultan mentioned that he was endeavouring to regain full control over Oman from the Imamate, based at Nizwa, and was unable to develop his country fully due to lack of funds. He then suggested ceding Gwadar to the Government of India in return for financial assistance.

Hickinbotham suggested in his report to the Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. at Bushire that there were three possible courses of action: to make a substantial financial contribution to the Sultan in return for Gwadar, to refuse further financial assistance altogether, or to take over Muscat and Oman outright. The first of these options would mean giving the Sultan ‘a very considerable sum of money in return for very little’ and did not promise a long-term solution.

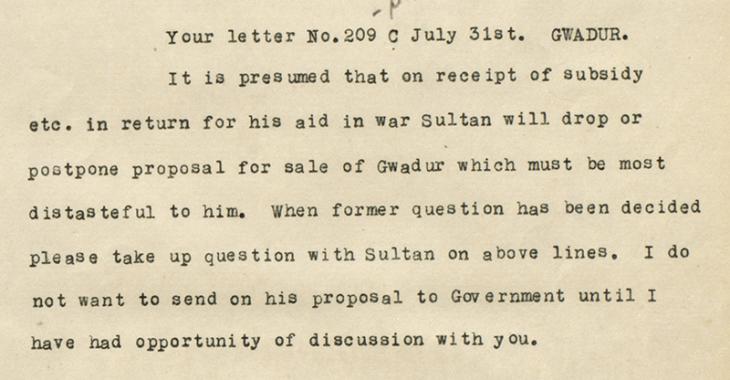

Hickinbotham’s preferred option was to take over Oman, install a British garrison and leave the Sultan as titular head. In his reply, the Resident doubted whether the Sultan, if he received a financial grant, would go through with the sale of Gwadar, as such a sale would be ‘most distasteful to him’. Further discussions followed later that year.

The papers present a revealing insight into attempts by one of the Gulf’s rulers to bargain for political and financial advantage through diplomatic contacts with representatives of the British government, and British calculations about whether it was in their interests to acquire direct control over further territory in the region.

India’s Independence and the End of the Dispute

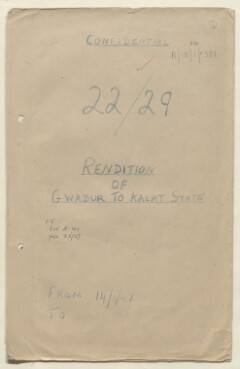

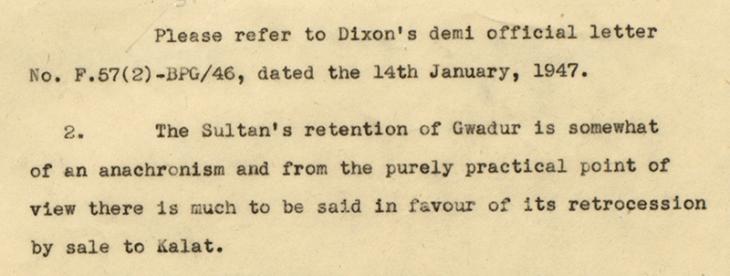

Following the Second World War, the issue of the transfer of Gwadar to Kalat re-emerged, with the British still keen to resolve the dispute. However, the Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. in Bushire remarked in a letter of 1948 that while the retention of Gwadar by Sultan Sa‘īd bin Taymūr was ‘somewhat of an anachronism’, the Sultan was the sort of monarch who ‘usually clings to every inch of his territory’, and so would be unlikely to consider disposing of Gwadar. The only qualification would come if the Sultan’s own proposal of 1939 were to be revived and if he were to be offered funds in return.

Britain’s involvement ended in 1947 when India became independent. Omani Gwadar finally came to an end in 1958 when Sultan Sa‘īd bin Taymūr sold the territory to Pakistan for three million US dollars. At this time, it was still quite an insignificant place.

In the 1990s, however, the Pakistan Government decided to recognise Gwadar’s strategic potential by developing it as a major deep-sea port with connections to the country’s road and rail infrastructure. Gwadar has since received significant Chinese investment. Although Sultan Sa‘īd clearly got a good deal by holding out until 1958, Gwadar today appears to be an even more important possession.