Overview

Papermaking history and early development

There has been much discussion in the world of conservation regarding watermarks in paper, most of which focuses on their use as possible indicators of date and provenance. However, less is said about the origins of the designs themselves. The first known watermarks can be traced back to Italy in the late thirteenth century, with their initial purpose documented as being a means of indicating that papers were locally made, not imported. By the nineteenth century, the practice of watermarking papers was widespread and production methods were becoming more industrialised. At this point, it became common for watermark designs to include a combination of the papermill’s name or mark (akin to a company logo), a date, and the name or initials of the papermaker themselves. However, this was not the case when the practice was in its infancy.

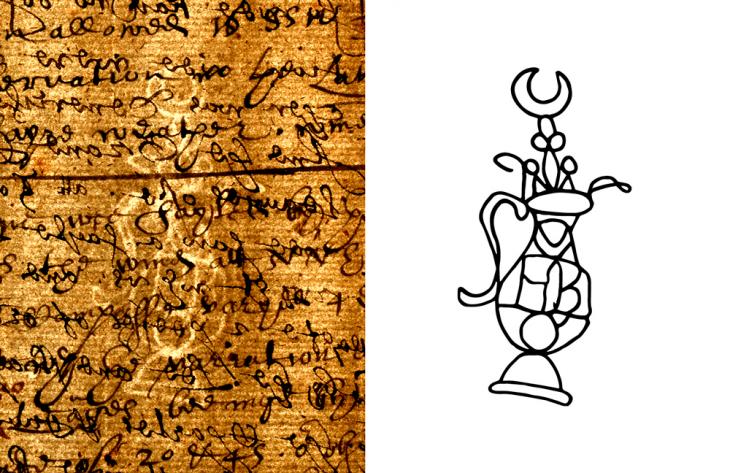

Originating in China, papermaking techniques spread through the Arab world from the eighth century, and were brought to Spain by North African Muslims. The practices were quickly adopted across Europe, with Italy becoming one of the first main centres of production. Greater access to waterpower enabled Italians to produce cheaper papers which, by the fourteenth century, were widely distributed and traded in the Islamic world.

Early papers produced in the Arab world do not feature watermarks and differ from European papers in their appearance and construction. One of the main differences in production is the use of organic materials rather than wire to construct the fine mesh on which the sheets are formed. This accounts for the marked differences in the appearance of laid and chain lines, and also does not allow for the possibility of attaching watermarks (which are constructed from fine wire) to the moulds. However, some thirteenth-century papers made in Spain using this technique feature a ‘zig-zag’ mark, which would have been created in the papers before drying. The purpose of such marks remains unclear, but they have been referred to as possible precursors to watermark designs. The zig-zag marks may have been used to indicate the grain direction within papers, but the most recent research suggests they were used to thin the paper where it was to be folded in order to reduce ‘swelling’ in the spines of books when the papers were bound.

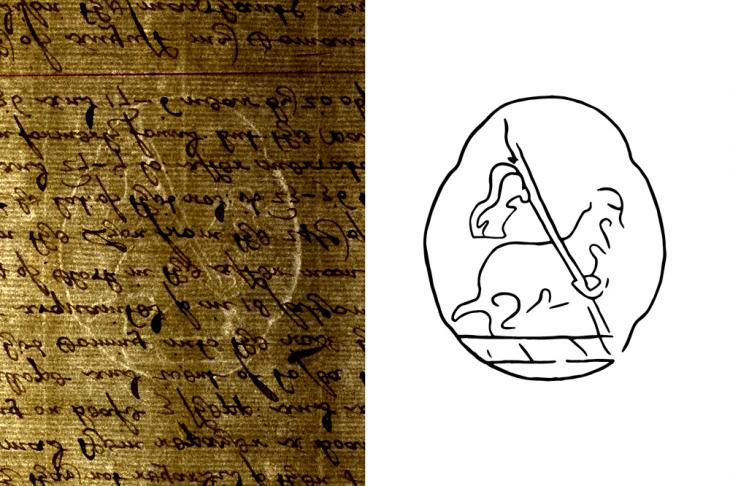

It was the Italians’ adoption and development of papermaking technologies from the Arab world which led to the implementation of watermarks as we recognise them today. The very earliest designs feature symbols relating to early Eastern Arabic numerals, later superseded by designs such as the Italian anchor watermark, and later by the ‘three crescent moons’ (tre-lune), commonly used in papers manufactured for export to the Arab world.

Historical context and early use

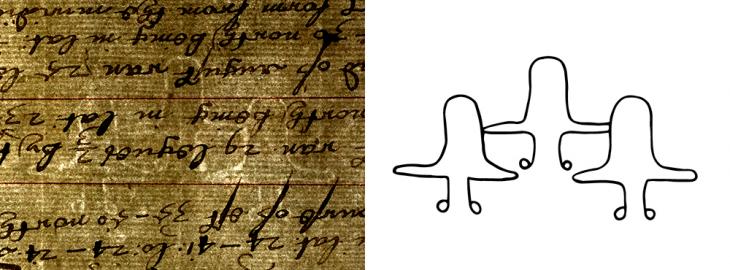

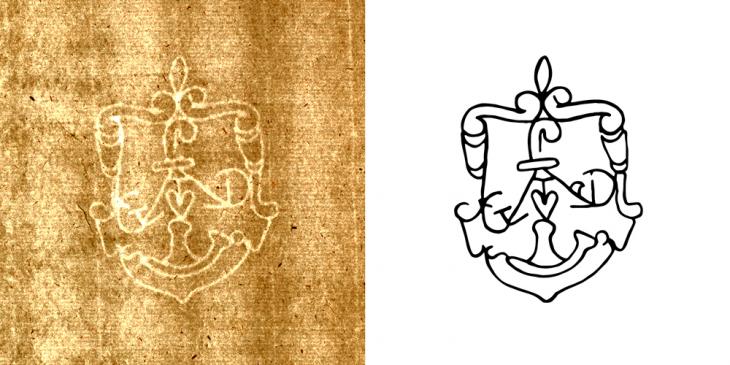

In order to understand the origins of early watermark design, it is important to frame the process within the context of the period of its development. During the late Middle Ages, the workshops of artisans and merchants across Europe were organised into guilds. Papermaking guilds were established in the fourteenth century, beginning life as auxiliaries of the wool guilds. Like all workers of the period, papermakers were required to mark their products with their own identifying symbol, recorded in an official guild book. The city of Fabriano in Italy was one of the earliest hubs for the dissemination of paper throughout Europe and the transfer of papermaking techniques from the Arab world. It was also the birthplace of the watermark, and home to the historical paper collection of Augusto Zonghi, which comprises papers manufactured in Fabriano between 1267 and 1798. Among the documents housed in the Archivio Storico in Fabriano is a fourteenth century wool guild registry book, which lists members by name, and shows the unique identifying mark of each. The symbols used by the wool guild workers in the fourteenth century bear a close resemblance to those used in the watermarks of the period. Furthermore, the early manuscripts within the Zonghi collection feature watermarks related to the industry with which they are associated; for instance, there is a spinning wheel watermark in the record book for the cloth guild.

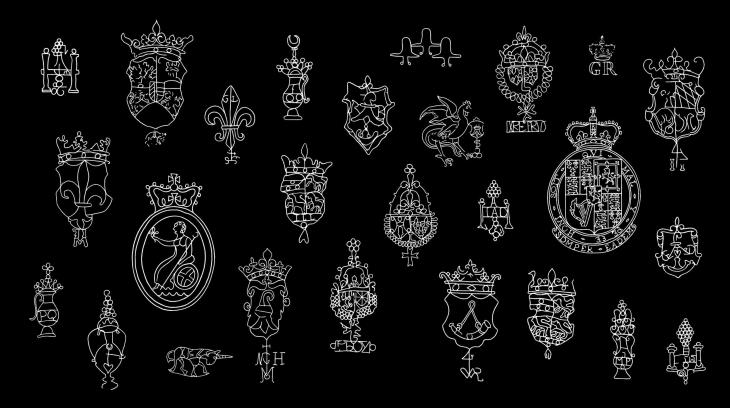

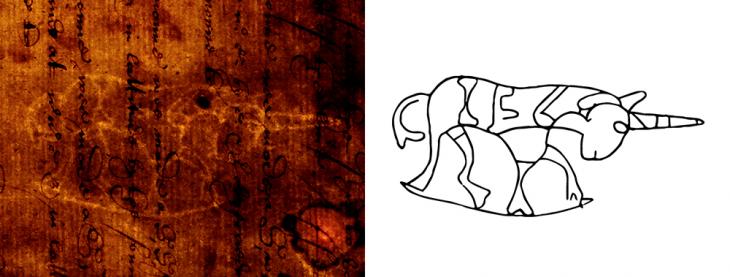

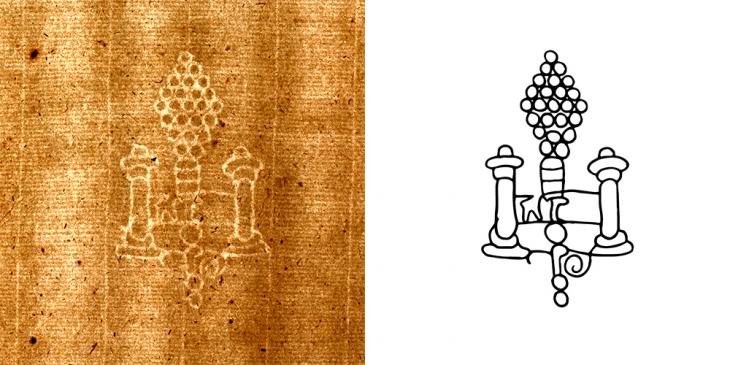

Occasionally, early watermarks feature the full names of papermakers but were later replaced by representative designs, such as the ‘Three Hat’ motif, which bears a distinct resemblance to flying saucers (see above). As was common with other insignia, watermarks later adopted more creative imagery, including animals, religious symbols, and tools. In the mid-fifteenth century, Fabriano itself became an ecclesiastical state, and the papal insignia was then routinely used as a watermark. Monasteries in the area also regularly leased their sites to papermaking workers and remained closely associated with the craft. Papers made at the Benedictine Abbey of Montefano in Fabriano bear watermarks with the Benedictine order’s three hills insignia.

Further developments

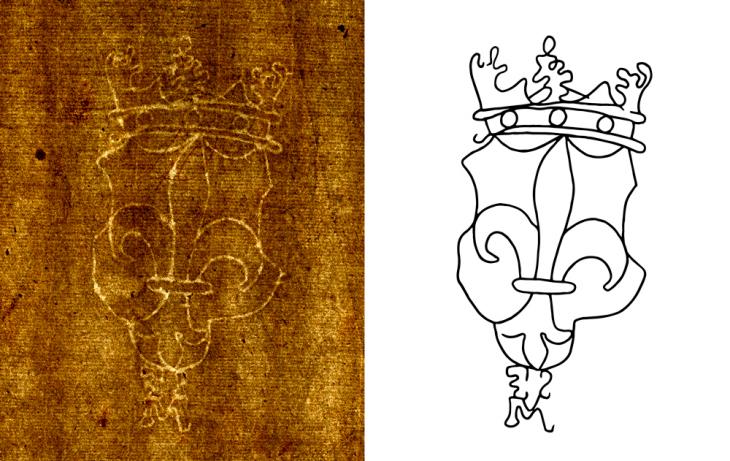

Similarly, the insignia of aristocratic families were increasingly likely to be used as watermarks by the mills they owned and patronised. In her recent publication, Fabriano: City of Medieval and Renaissance Papermaking, Sylvia Rodgers Albro suggests that this heraldic tradition, the imagery of which is more commonly associated with later watermarks, originated from the battles fought between European knights and Turkish and Arab forces. The latter used shields displaying identifying insignia, and by the thirteenth century a similar heraldic practice had been widely adopted by European nobility.

The practice spread to religious organisations, monastic orders, merchants, tradesmen, craftsmen, and guilds.

Looking at these early examples in context, it is possible to see how the origins of watermark designs likely relate to guild imagery and the identifying marks of the papermakers.

Guilds acted as regulators of trade and commerce, but also served religious functions. It is therefore unsurprising that their insignia contain a mixture of both religious imagery and that related to the secular or heraldic aspects of a guild’s work.

There are however more unconventional theories around the origins of watermark designs, such as Harold Bayley’s The Lost Language of Symbolism (1912). Bayley links their symbology, and the papermaking trade itself, to the many mystical and ascetic sects operating in Europe during the Middle Ages. Bayley claims that papermaking was one of the most developed trades of organisations such as the Albigeois and Vaudois in France, and the Cathari and Patarini in Italy. He argues that watermark designs were employed for their symbolic significance, and used as a form of emblematic religious propaganda by these “heretical” sects.

What is certain is that at such a time when few could read or write, developing visual forms of communication was essential, its use being prevalent in forms as varied as inn and tavern signs, seals, and guild imagery. The late Middle Ages and early Renaissance were synonymous with the use of symbolic and allegorical imagery, the influence of which appears to have penetrated the very paper on which it was drawn.