Overview

The Garland Encyclopedia emphasizes that “the region has produced a plethora of song genres”. If one only steps in the very recent history of the countries along the upper Gulf coast, that is Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar and the eastern coastal region of Saudi Arabia, one is surprised at how many active musicians and singers this region has produced. The Kuwaiti based ethnomusicologist Lisa Urkevich states that “the Arabian Gulf is historically one of the most musical regions of the Peninsula”.

In particular, the extensive pearl-diving and sea trade activities with regions as far as India, Africa and Persia, and the trade connection with inner Arabia created and cross-fertilised a rich and multifaceted music culture in the region. This mainly took place before the exploitation of oil in the 1940s.

This article provides an overview of the most common musical genres prevalent in the Gulf region; it corresponds to the article about musical instruments, titled A Rich Culture Expressed in Music - Musical Instruments in The Upper Gulf Region.

Genres Grouped According To Their Origin

We can group the main musical genres according to the natural environment – mainly the land and the coast – where the people live, and to the origin of musicians. Although these are completely different environments and influences, there is a connection: the importance of the voice, the striking interlocking pattern and the extensive and creative use of poetry.

Since there are many musical genres, this article will only mention the most important types and loosely group them into three main categories. These categories are not clear-cut, as communities have always exchanged cultural traits; for instance, singers and instrumentalists of sea music often perform music with strong roots beyond the Gulf as well.

If the music of the upper Gulf is hardly known outside the region, the musical practice of female musicians and singers is even more hidden. Exhibited especially during weddings, and (until recently) within communities along the coast, women were and are extremely skilful as singers and even drummers. For instance, Lisa Urkevich mentions several genres where women participated in dance and instrument playing.

Music from the Sea

Sea music researchers Poul Rovsing Olsen and Ulrich Wegner call the music of the pearl divers “the most refined music-making of the area”. Sea music (in Arabic fann al-baḥri), that is music related to fishing, pearling and the sea trade, is not only the most sophisticated music of the region, but is also the most important group of the genres.

Most scholars group these genres into work songs (previously the most important group) and leisure time music called fijiri. Work and fijiri music consist of many different subgenres and songs. For instance, every single activity on a boat – such as pulling the anchor - required a specific song and rhythm and therefore the repertoire was huge. With the demise of pearling and the use of sailing boats, many genres became extinct or seldom performed.

Fijiri was performed at the start and end of the pearling season, on the large trading ships and in the dār (in Bahrain and Qatar) or dīwāniya (in Kuwait). A dār was often only a small hut along the beach where sailors met to chat, drink tea and coffee, and foremost to make music and sing. This tradition continues to exist among the descendants of sailors, nowadays in dedicated rooms in private houses.

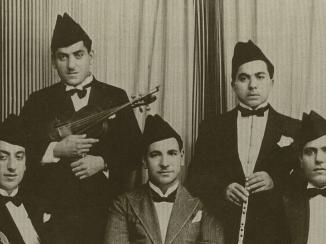

The musical genre ṣawt originated in the small coastal town centres of Kuwait and Bahrain. Essentially, it is an urban music combining influences from the local Bedouin and fishing communities with music from Yemen, Saudi Arabia and Egypt. Sawt mainly consists of two completely interwoven elements: the scales and method of playing the string instrument oud, which are taken from Classical Arabic music, together with the polyrhythmic structures and lyrics taken from Gulf communities’ musical traditions. The singer and oud player are supported by the violin and the mirwās drum.

Music from the Land

In her book Music and Traditions of the Arabian Peninsula, Lisa Urkevich, for instance, distinguishes between influences from the Badū (itinerant) and Haḍar (settled) communities.

Al ‘arḍa is the quintessential dance-song genre still performed by most tribes in the region. The musical instruments are ṭabl baḥri and the ṭār. In the coastal region, this old battle dance has been slightly modified: in comparison to the non-coastal areas in Saudi Arabia, the expression of the dance is less belligerent and little bells attached to the rim of the ṭār create additional sound.

Rebāba refers to the genre and the instrument; a small, bowed, one-stringed instrument with a resonant body covered with goat or wolf hide. The singer recites poetry and accompanies it with this instrument. Although often regarded as a typical Badū genre, it is equally regarded as part of the Haḍar cultural heritage (see Urkevich).

Regional Music with Strong Roots outside the Gulf Region

Though the performers of these genres – such as laywa, habbān and ṭanbūra – have strong roots in East African and Persian cultures, they have become part of the regional culture of the Gulf.

Sea musicians still perform these genres at the beginning or end of their sea music and ṣawt performing sessions in dār, dīwāniya, majlis or in public.

The origin of laywa can be traced to the east African coast, mainly Tanzania and Kenya, the ṭanbūra to southern Egypt and Sudan, and the habbān to the Iranian coast. Communities with roots in Africa or Persia perform this music very seldom and always in private, as part of ritualistic or heeling activities.

In laywa, the leading instrument player – the ṣurnāy ‘oboe’ – moves between the dancers and other instrumentalists. The relatively large percussion group is set in the centre while the dancers move around anti-clockwise and in measured steps. The instrument group consists of the drums ṭabl al ‘oad, musūndū, chechānga and the idiophone bātū or jigange.

Tanbūra denotes the main instrument, a triangular lyre, and the genre. The singer accompanies himself on the lyre while sitting on the floor. The drum players (ṭabl Nubia) sit to the right and left of the lyre player. Two or more dancers in front of the instrumentalists move their lower bodies to create rhythmic sounds with their manjūr rattle belts. In a right angle to the instrumentalist, two rows of line dancers facing each other move inwards and outwards.

Today, especially in Kuwait and Bahrain, many of these musical traditions are still maintained within the private dīwāniya / dūr (sing. dār), through government sponsored groups and by listening to rescued old recordings mainly from shellac discs.

Listen to:

Playlist Kuwait:

Playlist Bahrain: