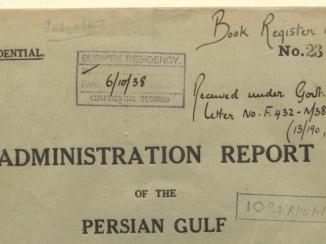

Overview

In the first half of the twentieth century, British officials assumed responsibility for the administration of justice in cases that concerned British subjects and certain classes of foreigners in the Gulf. However, this led to frequent discussions and occasional disagreements with rulers of the Gulf States over the precise definition of areas of judicial responsibility.

Judicial Responsibility in Context

The British right to exercise extra-territorial jurisdiction in the Gulf began in the nineteenth century in the shape of informal agreements with various rulers. Amongst the treaties signed was one between the British Government and the ruler of Bahrain, Shaikh Isa bin Ali Al-Khalifah, in 1892. The treaty provided Bahrain with British ‘protection’ and prohibited Shaikh Isa from dealing with other foreign powers, more specifically Ottoman officials.

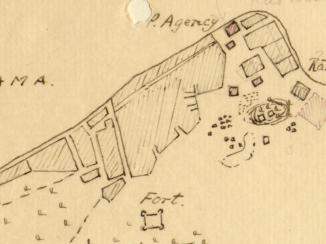

But such treaties could not prevent a growing encroachment of foreign interest in the Gulf in the first decade of the twentieth century. In Bahrain, for example, the American Mission opened a hospital in Manama in 1903. Three years later, the German firm Wonckhaus & Company arrived, wasting no time in muscling in on Bahrain’s pearl and shipping trade. Britain also took close note of the movements of Russian and French Government agents passing through the Gulf. Would the growing presence of foreign interests pose a threat to British rule in the Gulf?

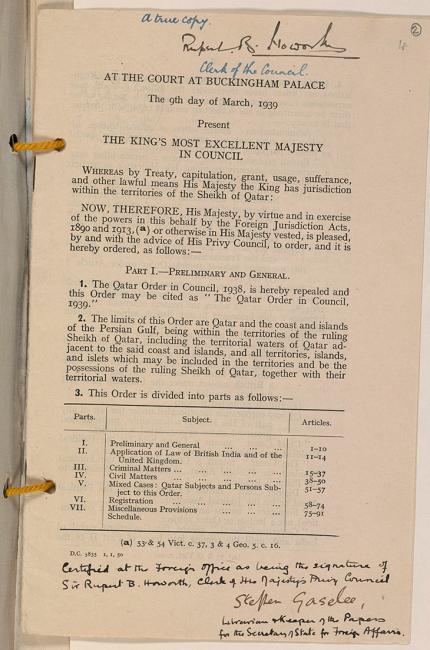

Orders in Council

The British response to this threat was to administer justice in the region under the authority of Foreign Jurisdiction Acts. These acts empowered the Crown to establish courts of justice and to legislate for those persons subject to their jurisdiction, by means of Orders in Council A regulation issued by the sovereign of the United Kingdom on the advice of the Privy Council. . The British Government promulgated the Bahrain Order in Council A regulation issued by the sovereign of the United Kingdom on the advice of the Privy Council. in 1913, though it did not take effect until after the war in 1919. Further separate orders included those promulgated by the British Government for Kuwait (1925) and Qatar (1938).

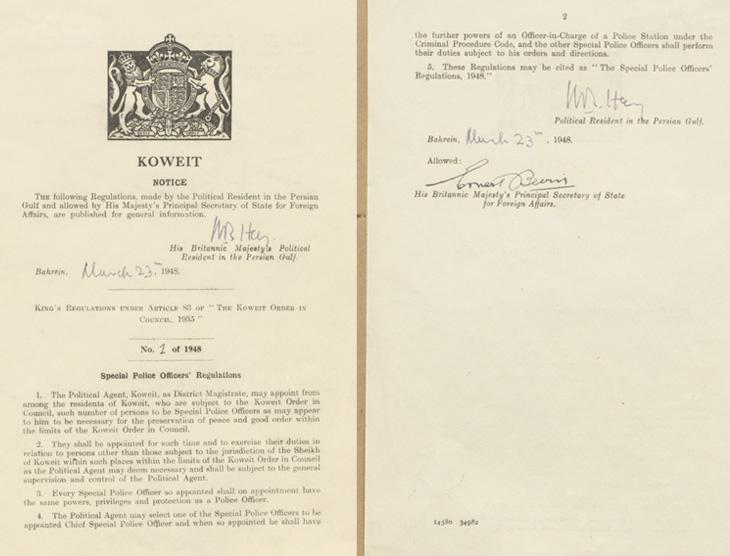

The Orders in Council A regulation issued by the sovereign of the United Kingdom on the advice of the Privy Council. were backed up by King’s Regulations, which gave the right to the Political Agents to establish courts in their various districts. As members of the Indian Political Service The branch of the British Government of India with responsibility for managing political relations between British-ruled India and its surrounding states, and by extension the Gulf, during the period 1937-47. , the Agents would be expected to have had some judicial experience. Meanwhile, the Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. at Bushire acted as judge of the Chief Court, which normally only heard appeals.

From Slave Trade to Pilgrim Ships: Legal Business

Legal business became an increasingly important part of the work of both Residents and Agents. The Political Agent’s court at Bahrain was particularly busy, and by 1944 the Agent complained that his assistant was occupied for at least one whole day each week trying cases. Measures were passed for the administration of justice in Bahrain, Muscat, the Trucial Coast A name used by Britain from the nineteenth century to 1971 to refer to the present-day United Arab Emirates. , Kuwait, Qatar and the Persian Coast and Islands. The measures set down rules for the operation of the courts, registration of British subjects and a variety of special issues, such as the slave trade, Christian marriage, the safety of Indian Pilgrim ships, the import of cultured pearls, traffic in opium from the Persian Coast, illegal arms dealing, municipal sanitation, and the appointment of police officers.

The papers of the Bahrain Agency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, headed by an agent. throw up a number of issues specific to the region and the operation of ordinary judicial procedures that could occasionally have ramifications which affected relations between neighbouring Gulf States.

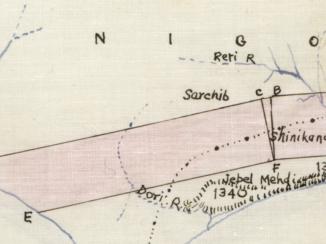

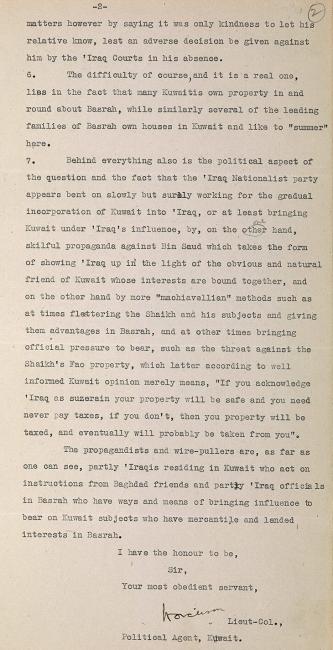

Iraqi Nationalists and the Threat to Kuwaiti Independence

Thus, in a letter dated April 1930, Lieutenant Colonel Harold Richard Patrick Dickson, the Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. in Kuwait, asked the Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. in Bushire, Lieutenant Colonel Hugh Vincent Biscoe, whether Iraqi courts had any right to ask his Agency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, headed by an agent. to serve summonses and other legal documents on individuals residing in Kuwait, especially ‘seeing that Kuwait is for all intents and purposes an Independent State’. The difficulty was that many Kuwaitis owned property in and around Basra, while several of the leading families of Basra owned houses in Kuwait and liked to ‘summer’ there.

Dickson feared there was a political aspect to the issue: ‘the Iraq Nationalist party appears bent on slowly but surely working for the gradual incorporation of Kuwait into Iraq, or at least bringing Kuwait under Iraq’s influence’. By threatening to tax or appropriate mercantile or landed interests at Basra, the Iraqi ‘propagandists and wire-pullers’ hoped to bring pressure to bear on influential Kuwaitis to acknowledge Iraq as having supremacy over their state.

It is clear that conversations on the matter between the British and the Sheikh of Kuwait, Aḥmad al-Jābir Āl Ṣabāḥ, who was keen to establish a reciprocal arrangement with Iraq on the service of judicial documents, revolved around avoiding doing anything that would undermine the principle of Kuwaiti independence.

Changing Circumstances in the 1930s

The 1930s was a time of change in the nature of the British Government’s assumption of jurisdiction over foreigners in the Gulf, especially in view of the number of non-Muslim foreigners – particularly Americans – arriving to work in the oil industry. Clearly, although Britain was formally solely responsible for such judicial decisions, sentences could not be pronounced without considering the complex and delicate balance of power in the region as well as the political repercussions for those rulers over whom Britain exerted power and equally on whom Britain relied.