Overview

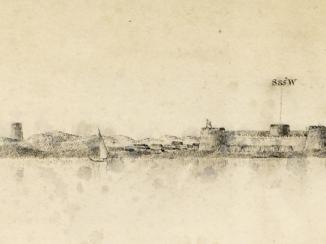

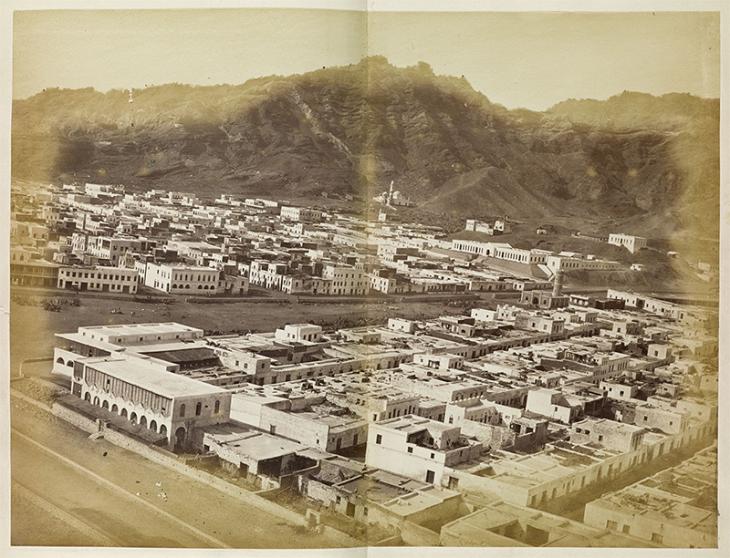

In 1839, when the British occupied the important commercial port of Aden they expected to find remnants of an ancient metropolis. Instead, they found a decrepit village with approximately one hundred adobe (baked mud) houses with the rubble of fallen buildings blocking the streets, neglected wells and a ruined aqueduct. Even the fortifications were in ruins.

A Vital Trading Port

The Bombay Government was interested in both the commercial and military aspects of the town and hoped that Aden (also known as Crater) would once again become a great commercial port that would facilitate British trade to and from India and beyond. But, in order to secure British control over the region, existing fortifications had to be reviewed and the appropriate site for a military camp had to be chosen and garrisons designed.

The Special Committee

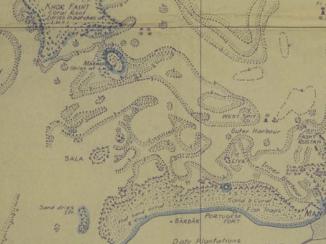

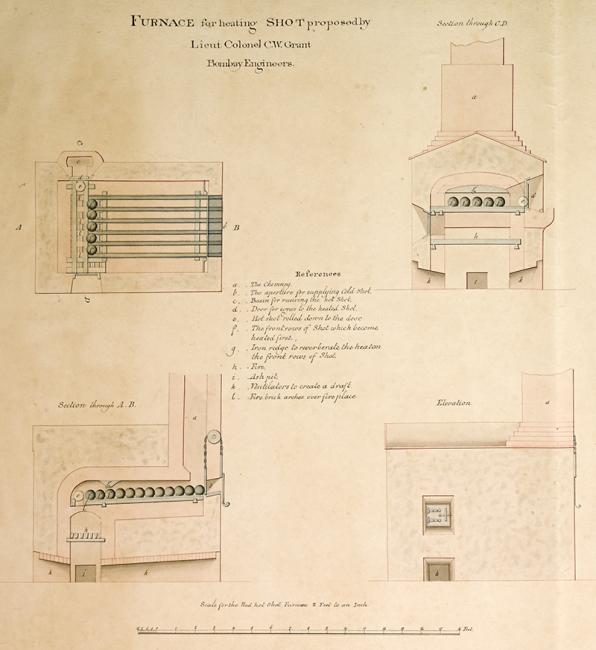

Plans, sections and views of Aden and the surrounding area, of which a large proportion were devoted to the proposed military camp site, were drawn up by a Special Committee formed of Majors William Jacob from the Brigade of Artillery, and C.W. Grant of Corps of Engineers in 1843. These were copied and sent to London and Bombay for consultation and approval.

Natural Defensive Features

For military cartography, geographical data is vital in the assessment of terrain in terms of defensive strategy. The Special Committee recommended taking advantage of the terrain’s protective features, which provide natural defences. Under their plans, the settlement was to remain in Crater, which was well-protected, with the garrisons based in the Isthmus. The proposed campsite would be guarded by precipitous cliffs ‘scarped where necessary, and cut into a parapet and ditch the whole line being flanked by guns in various batteries’. In addition, ‘long swell and heavy surf beat against the coast for 8 months of the year rendering it inaccessible’.

Construction

Some fortifications would have to be built, however. The coastal defence would include a ‘pier of obstruction and landing pier protected by a guard room and battery built against the bluff, and containing a reservoir, filled by iron pipes from the camp, for the supply of water to the shipping in Western Bay and at steamer point’.

Detailed information gathered and incorporated in the plans also included ‘works against Arabs’ and ‘Advanced Redoubt required only against an attack by European Forces’. Interestingly, this indicates the British expectation that not only local Arabs, but also another European force, most likely the French, might at some point challenge their occupation of Aden.

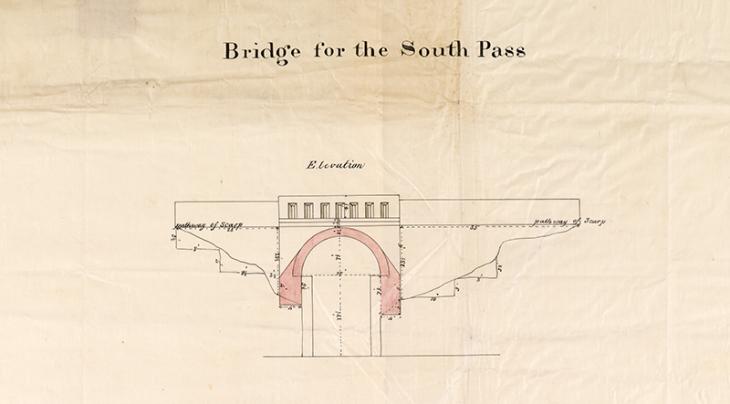

Water, Shot and Rafts: Building for the Troops

Man-made constructions, including a hospital building, casemates (bomb-proof, vaulted chambers) for the British soldiers and barracks for the Sepoy Term used in English to refer to an Indian infantryman. Carries some derogatory connotations as sometimes used as a means of othering and emphasising race, colour, origins, or rank. troops (Indian soldiers), appear in the form of architectural drawings including frontal views (or elevations) and a floor plan with measurements reported. A network of iron pipes supplying water to reservoirs for ‘native troops’ and separate clay water tanks intended for the British soldiers, were also integrated in the Committee’s plans, alongside technical devices such as a ‘traversing platform’, ‘a raft for extending a Pier into deep water’ and a ‘furnance for heating shot’.

Improvements to the communication infrastructure, critical to determining the ability of forces to hold areas and move troops and material, were recommended. This included ‘a military road from the Valley of Aden to the New Cantonment’ and ‘cut across the Narrow Ridge terminating the Position on the Heights’.

The series of plans and sections produced by Jacob and Grant make clear their extensive knowledge of the peninsula, which they acquired during their short stay in Aden. Their work enabled officers based elsewhere to understand the topographical features of the area and thereby influenced their decisions.

In London, the Court approved the Committee’s plan. However, Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Hardinge (later Lord Hardinge), the incoming Governor-General, inspected the defences of Aden on his way to India. In his opinion, the defences had been planned on an unnecessarily large-scale, so he recommended that the fortifications should be constructed sufficient only to ‘keep the population in check’ and to resist an attack by Arabs or by a small European force. Hardinge had his way and it was decided that the fortifications should be built on a reduced scale.

Nevertheless, the physical geography of the terrain was expressed so clearly that the maps and plans can, even now, be compared with modern-day satellite and street-level mapping services.

The topographical representation documented by the Committee in such great detail provided an invaluable visualisation of the territory for the establishment of a settlement – later a colony – that was vital to facilitating trade and shipping routes to and from India over a hundred year period.