Overview

A Voyage of Firsts

The Third Voyage of the East India Company (EIC) (1607-10) was the first to be organised after the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604). It was also the first English voyage to reach India, following the route established by the Portuguese nobleman and later viceroy of India, Vasco da Gama, in 1498. The main intention was to build trading relationships with various strategic ports in the Red Sea and Indian Ocean. Although a long and challenging process, this ambition was partially achieved. The journals kept during these voyages shed light on some of the first interactions between English crews and the local populations on the coasts of Africa, the Gulf, and Asia, and provide a vivid insight into life at sea in the seventeenth century. Within the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. Records, there are seven ship’s journals that were written during the Third Voyage, five of which are available on the Qatar Digital Library.

The voyage: difficulties from the outset

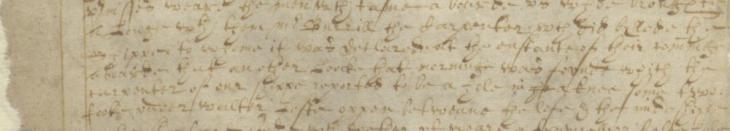

There were three ships at the outset of the voyage: the Red Dragon, captained by John Keeling; the Hector, captained by William Hawkins; and the Consent, captained by David Middleton. The Consent, however, departed a day ahead of the other two ships and made its whole journey independently.

![Journal entry listing the three ships and their captains at the outset of the Third Voyage, March 1606 [1607]. IOR/L/MAR/A/V, f. 4r](https://www.qdl.qa/sites/default/files/styles/standard_content_image/public/ior_l_mar_a_v_0012_0.jpg?itok=NPVDNte0)

From the very beginning, there were both practical and personnel difficulties. Before departure, there were delays in assembling crews, followed by desertions throughout the journey. Then, before it had even left the English Channel, the Hector sprung a leak which had to be repaired before it could continue sailing.

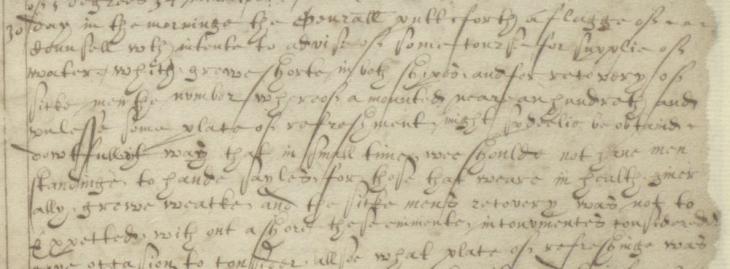

Throughout the voyage, one of the biggest difficulties was the proper provision of food and water. On multiple occasions, the journals record that the captain needed to enforce rationing until the ship arrived at its next stop and could replenish supplies. The lack of full rations inevitably affected the health of the crew, and several times the ships needed to dock at various ports for long periods to allow the men to recover from bouts of sickness. It was typical of this kind of journey that many seamen would lose their lives, and this particular voyage was no exception.

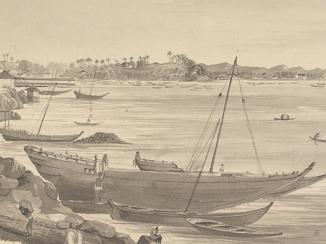

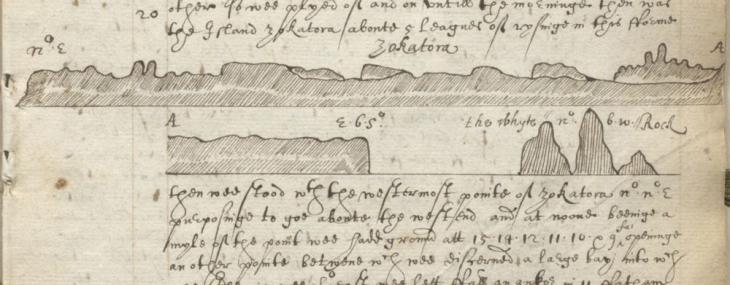

Socotra

Despite the ongoing challenges of seafaring, the Dragon and Hector made their way around the coast of Africa, eventually arriving at Socotra. Situated between the Gulf of Aden and the Arabian Sea, the island had long been a port linking the Red Sea and India, and over centuries and even millennia had seen the arrival of Arab, Greek, Indian, and Portuguese sailors and traders, long before the appearance of the EIC.

While the inhabitants of Socotra may have been accustomed to merchants visiting from around the world, the journals depict them as fearful and hostile. One of the journals claims this was because the Portuguese had been capturing and selling them to the Ottoman Turks as slaves.

On 22 April 1608, John Hearne and William Finch of the Dragon and Anthony Marlowe of the Hector record walking around a completely deserted town built out of stone. Searching for the inhabitants, they describe their own curiosity to discover what was inside the houses. Inside one, they found many types of spices and medicinal plants including aloe socatrina, turmeric, frankincense, mastic, sanguis draconis (probably in the form of gums and resins), and incense. Marlowe stresses that Hawkins had ordered them not to loot or damage any property, allegedly to differentiate their behaviour from that of the Dutch and Portuguese.

Keen to communicate with the local population (most likely in Portuguese), they made their way to another settlement, and approached waving a white flag. The local inhabitants did not permit them to stay, but eventually at the town of Tammarie [Tamridah] they established contact and friendly relations with Sedj Hamour Bensaid [Sayyid ʿĀmir bin Saʿīd], King of Socotra, and exchanged presents.

From Socotra, the ships separated, the Hector towards India, and the Dragon to Sumatra and Java. The Hector reached its destination on 25 April 1608, making it the first English ship ever to enter an Indian port. The ships reunited in December, at which point Captain Keeling assumed command of the Hector and sent the Dragon back to England, carrying a full cargo of cloves. The Dragon reached Plymouth in September the following year. In the meantime, Keeling took the Hector to try to open trade in the Banda Islands, but he was unsuccessful and was forced to return to Bantam. From there, he departed in October 1609 heading back to England with a cargo of pepper, arriving in May 1610. Overall, the Third Voyage was immensely lucrative for the English, returning a profit of 234%.

Analysing the journals

Like most of the early EIC journals, the seven recording the Third Voyage exist only as incomplete fragments. They were often written by the captain, but there are also entries by other senior crew members. Most of the writers are named, but at least one is anonymous. It was customary to keep more than one journal for each ship in order to prevent losses or oversights, and to allow comparisons between multiple versions which would later be collated into an accurate account for future reference.

Over the many centuries of EIC voyages, the journals became more regular in structure and tone. However, these early seventeenth-century journals are much more variable in style. Some strike a personal note (IOR/L/MAR/A/IV), while others are more objective (BL Egerton MS 2100). Some give longer descriptions (BL Cotton MS Titus B. VIII, ff. 252-79), while others are short on detail (IOR/L/MAR/A/VI). The journals, like the ships’ cargoes, were corporate property, and therefore prioritise information useful for the EIC. However, some writers also add their personal opinions and write in the first person.

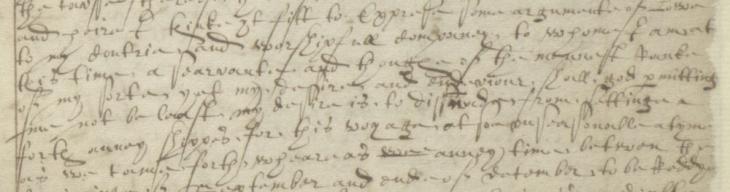

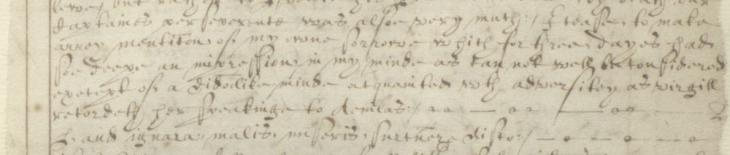

An unusual insight into the writer’s personality is provided by the anonymous author of IOR/L/MAR/A/IV. He seems the most literary of the writers, quoting Virgil in a moment of duress when the crew had been on strict food and water rations for days and had not been able to find a port to resupply: ‘Haud ignara malis, miseris, surcuere disco’ (‘Schooled in suffering, now I learn to comfort those who suffer too’). More than once, he refers to the Discours of Voyages by the Dutch merchant Jan Huygen van Linschoten (published in English in 1598), and the tone of his account is closer to that of an historical narrative than a ship’s journal.

The principles for how these journals were written can be traced back to the Ordinances of Sebastian Cabot (1553), later included in Richard Hakluyt’s compilation The principal navigation, voyages and discoveries of the English Nation (1598), which is mentioned several times in the journals. Cabot’s Ordinances served as a set of instructions for sailors to help write and prepare for the journey. They cover how the sailor should equip himself, how to manage a crew, how and when to make notes and of what, how to communicate with local populations, and suggestions on how to establish trade relations. The writing need not be eloquent or have long reflections. Rather it should be in the form of notes, written in the moment of the event or soon afterwards, and should be written daily. All of the journals from the Third Voyage follow Cabot’s suggestions.