Overview

Abū l-Ḥusayn ʽAbd al-Raḥmān bin ʽUmar al-Ṣūfī al-Rāzī (291 AH/AD 903–376 AH/AD 986) was an Iranian astronomer and astrologer closely associated with the Buwayhid dynasty in Iran and Baghdad, especially with ʽAḍud al-Dawla (died 372/983) and with Ibn al-ʽAmīd (died 360/970), and the vizier of Rukn al-Dawla (died 366/976).

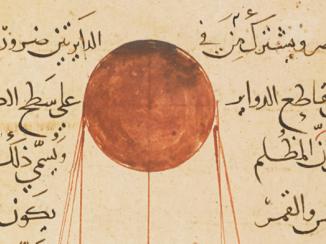

Al-Ṣūfī dedicated his Kitāb ṣuwar al-kawākib al-thābita (‘On the constellations of the fixed stars’) to ʽAḍud al-Dawla, and designed a meridian ring, thereafter named the ʽaḍudī ring (mainly used for making solar observations at midday when the sun crosses the meridian) for the determination of the the angle formed by the ecliptic and the equator (al-mayl al-aʽẓam). The ecliptic, or Zodiac, is the plane on which the apparent motion of the sun (according to Ptolemy) or the earth (according to modern understanding) takes place. Furthermore, Al-Ṣūfī made astronomical observations, patronised by ʽAḍud al-Dawla, and compiled a set of astronomical tables (zīj), a book on the use of the astrolabe Ancient instrument for astronomical observations. , an introduction to the science of astrology, and a didactical poem (urjūza, a form of poetry intended to instruct or teach) on the fixed stars.

Star Catalogues

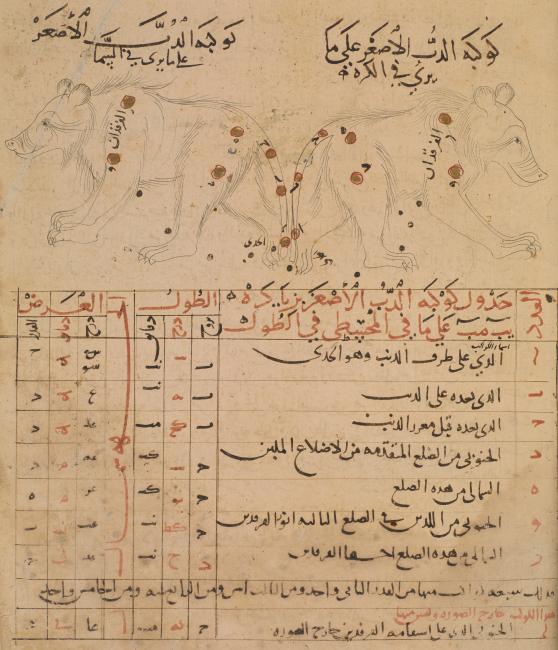

The earliest star catalogues – lists of stars and their coordinates and constellations – were produced by the ancient Greeks, and Books VII and VIII of Ptolemy’s Almagest contain his catalogue of stars. Each star is identified with a number within the corresponding constellation and by its position in the figure, for example, the first star of the Ursa Minor (or ‘Little Bear’) is the one ‘on the end of the tail’.

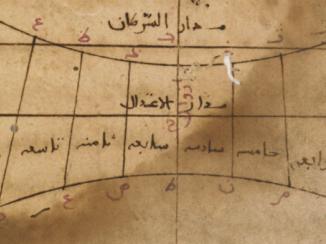

The catalogue provides the longitude, latitude and magnitude (relative size) of each star. Ptolemy’s values were accepted uncritically in the Middle Ages with the only correction of adding a constant to the stellar longitudes as a result of the ‘precession of equinoxes’.

In other words, the stars have been usually called ‘fixed stars’ because – unlike the sun, moon or planets – they do not appear to change their relative positions. However, they actually have a very slow motion which increases their celestial longitude by approximately 50” per year. This change cannot be observed during short periods of time but after a few centuries becomes obvious. This motion, called ‘precession of the equinoxes’, has been known from early antiquity, but was not physically explained until Newton (AD 1643–1727). Al-Ṣūfī’s revision corrected several star magnitudes and their relative positions in the constellations and identified many of them with a name later adopted within European astronomy. The figures depicted for each constellation formed the origin of an iconography diffused in both the Islamic and the Western worlds.

The Kitāb ṣuwar al-kawākib al-thābita

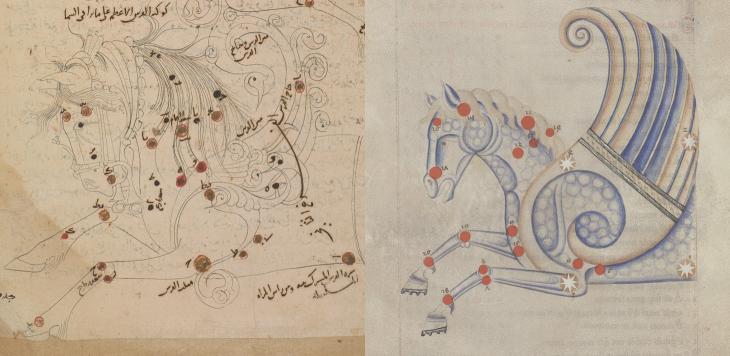

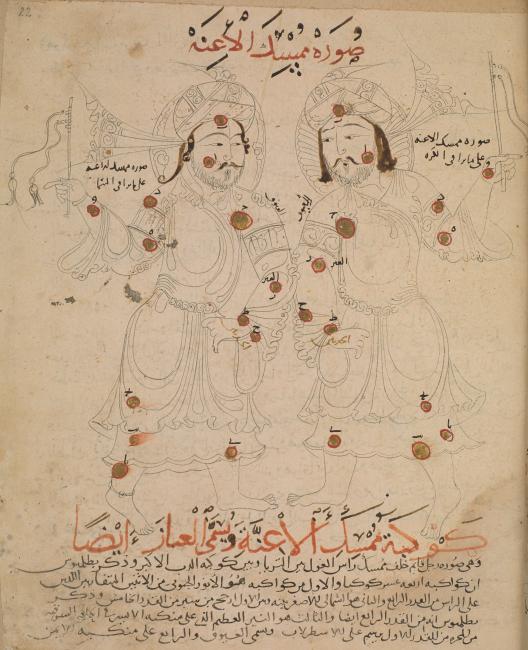

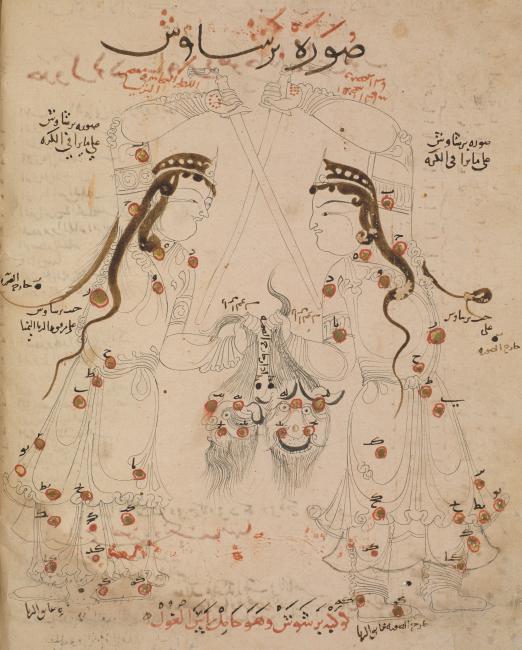

Al-Ṣūfī studied the forty-eight Ptolemaic constellations and his work was divided into three sections. The first contained comments on Ptolemy’s catalogue with occasional corrections to the magnitudes, the second covered materials derived from Arabic folk-astronomy and identification of the Arabic star names, and the third section comprised the star catalogue which kept the Ptolemaic latitudes, while longitudes were increased by 12º 42’ due to precession between 138 and 964 AD. Each constellation was represented in two illustrations (mirror images of each other) ‘as it is seen in the sky’ (ʽalā mā yurā fī l-samā’) and ‘as it is seen on the celestial globe’ (ʽalā mā yurā fī l-kura). Sections one and two also contained remarks on corrections to be introduced in Ptolemaic longitudes and latitudes of particular stars and references to new stars which were not mentioned in the Almagest.

The Importance and Influence of al-Ṣūfī’s Work

Al-Ṣūfī ‘s book is a good example of the Islamic critical appropriation of the Greek legacy. His star catalogue follows the Almagest but corrects the magnitude of 378 stars. Al- Ṣūfī uses the Ptolemaic six orders of magnitude but considers three steps within each one: aṣghar (smaller), akbar (greater) and aʽẓam (greatest). He adds eighty-four new stars and gives details about two new red stars – Ra’s al-Ghūl (Algol, β Persei) and al-Fard (α Hydrae). Furthermore, while Ptolemy described Sirius (al-Shiʽrā al-ʽAbūr, α Canis Maioris) as red, this star is not included by al-Ṣūfī in his list of red stars. Interestingly, Ptolemy is not the only ancient source that describes Sirius as a red star and this topic was under much discussion until the twentieth century. Concerning nebulas (saḥābī, laṭkha saḥābiyya and ishtibāk saḥābī), the book contains the earliest mention of the Andromeda nebula, rediscovered in Europe in the seventeenth century.

The figures of the constellations in al-Ṣūfī ‘s book have a Ptolemaic origin with substantial changes: the bleeding head of Medusa in the constellation of Perseus is replaced by a bearded ghūl (a demon of the desert). These images had appeared in Europe in the manuscripts of the so-called ‘Sufi Latinus’ since at least the twelfth century and were later divulged by the Alfonsine Libros del Saber de Astronomía in the thirteenth century. The astronomer Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī (597/1201–672/1274) translated al-Ṣūfī’s book into Persian and this translation was used by Ulugh Beg (796/1394–853/1449) in his star catalogue – subsequently edited, translated into Latin and commented on by Thomas Hyde (Oxford, 1665). Through this channel, al-Ṣūfī’s criticisms of Ptolemy, as well as his star names, became accessible to modern European astronomers.