Overview

On 8 April 1832, the Imam’s aunt, Mūzah bint Aḥmad Āl Bū Sa‘īd, wrote an urgent letter to the British following the capture and imprisonment of the Imam’s son and nephew. The presence of her name is striking in an East India Company (EIC) volume otherwise filled exclusively with the words and deeds of men. Yet, further examination of the sources reveals her to have been a powerful and respected individual who well warranted the attention of the EIC. And perhaps she was not alone among Omani women?

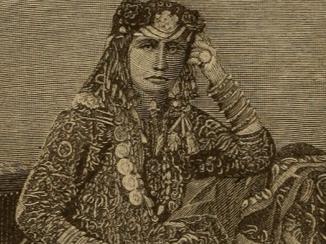

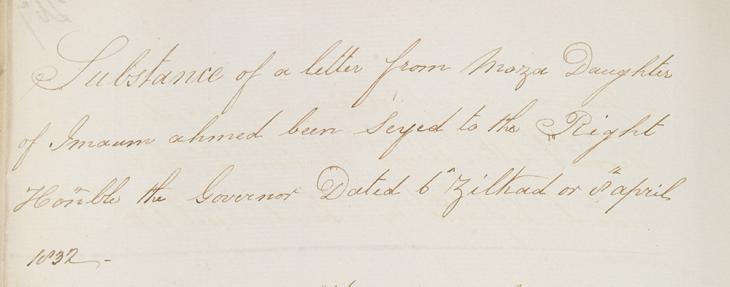

‘Moza, Daughter of Imaum Ahmed been Seyed’

This is how the British describe Muzah as the author of the letter. Notably, unlike many other women in the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. Records, Muzah is identified by her personal name and not solely by her connection to a male relative; nor is she described in relation to marriage or motherhood. She writes in her capacity as interim leader on behalf of her nephew, the Imam of Muscat Sayyid Said bin Sultan Al Bu Said, and requests support from his allies, the British. The ensuing papers document Muzah’s role in defending Muscat during a critical period of internal conflict and rivalry in Oman in the 1830s.

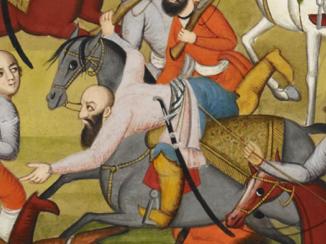

A rebellion on multiple fronts

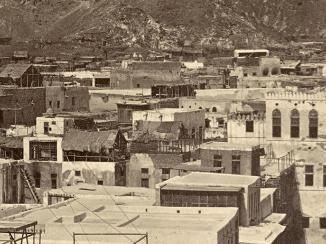

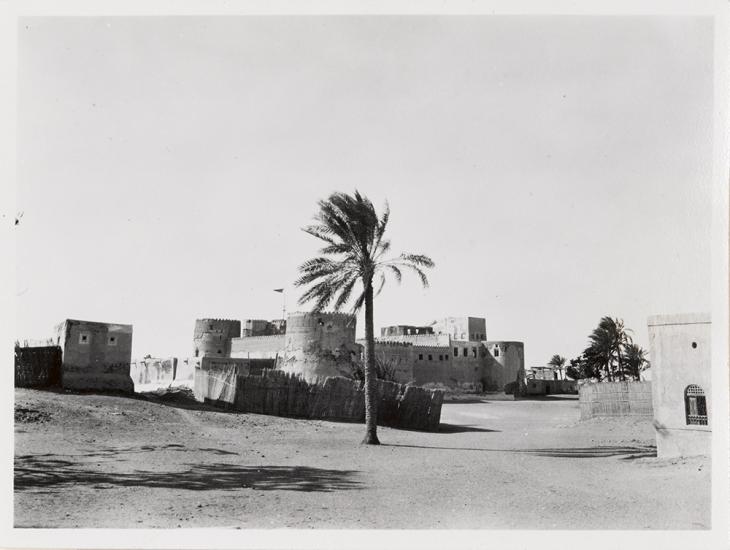

Copies of letters within the IOR/F/4 Series files describe how the Imam of Muscat had travelled to Zanzibar in December 1831, leaving in charge his son, Hilal bin Said, his nephew, Muhammad bin Salim, and their cousin Saud bin Ali, Shaikh of Barka. In March 1832, Shaikh Saud invited his cousins to rest at his fort during their tour of the interior. Not long after they had entered the building, the doors were locked, and Shaikh Saud had his cousins imprisoned. It was after this incident that Muzah wrote both to the Government of Bombay From c. 1668-1858, the East India Company’s administration in the city of Bombay [Mumbai] and western India. From 1858-1947, a subdivision of the British Raj. It was responsible for British relations with the Gulf and Red Sea regions. and to the Resident in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. requesting their aid. News also reached Muscat that Sayyid Hilal bin Muhammad, Shaikh of Al Suwayq, was working with Shaikh Saud, and that Hamud bin Azan, Shaikh of Ṣuhar, was launching his own campaign to capture Rustaq from the Imam.

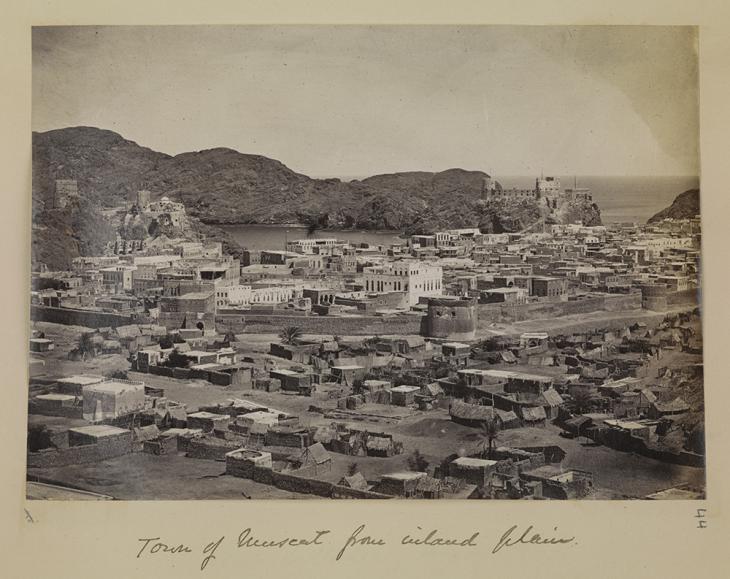

Writing to the Resident in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. , Reuben Aslan, the Company’s agent at Muscat, reports that the place was in disarray: residents on the outskirts had retreated into the city with their property, markets had closed, and people were ‘in the greatest terror’ (IOR/F/4/1435/56726, f. 242v). Springing into action, Muzah began recruiting troops and reinforcing Muscat’s defences by distributing gunpowder and shot to the city’s fortresses. She addressed an urgent letter to the Imam, and dispatched three envoys to Barka to ascertain Shaikh Saud’s intentions. She continued to press for British support, summoning Aslan to ask him for details on when ships from Bombay could be expected. The Resident acquiesced and instructed his assistant to arrange to send Company warships.

‘By the mercy of God and the courage of the Imaum’s aunt, Muscat is in perfect peace’

The Company’s broker Often a local commercial agent in the Gulf who regularly performed duties of intelligence gathering and political representation. at Muscat provided an update on 27 April, writing that the city had returned to order. Throughout the rest of the turbulent spring and summer of 1832, Muzah defended the Imam’s territories, excelling in her role as interim leader. If it were in any way unusual for a woman to take up such a role, no comment is made to that effect in any of the EIC’s subsequent correspondence. All those involved appear to readily accept Muzah’s authority – she is praised by the broker Often a local commercial agent in the Gulf who regularly performed duties of intelligence gathering and political representation. , and her requests for support are carried out by the British officials.

Recognised authority

Muzah was already an established figure in early nineteenth-century Oman, thanks to her involvement in helping secure Sayyid Said’s position at the start of his reign, which he had initially shared with his brother Salim. The nineteenth-century historian Ibn Ruzayq, referring to her as ‘the Imam’s daughter’, notes the different actions she undertook during this turbulent period, and consistently states that she had at least the same authority as her nephews (Arab.D.490, pp. 266-283). Meanwhile, Sayyid Said’s daughter Salmah bint Said, writing in the late nineteenth century, goes further in describing her great aunt as her father’s regent (Ruete, p. 160). From a British perspective, Colonel Samuel Barrett Miles, Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. and Consul at Muscat from 1872, may not call her regent but nevertheless mentions Muzah’s involvement as advisor and interim leader at several points during Sayyid Said’s long reign (Miles, p. 304, pp. 333-334, and p. 343).

The unnamed supporting role

While Muzah may appear exceptional within the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. Records material in that her personal name is provided, she is not alone as a female figure stepping up in the absence of male relatives to defend her family and their possessions. Within the same papers that report the events of 1832, a second woman appears in a comparable role. While the Imam’s nephew Muhammad was held captive in Barka, his captor Shaikh Saud marched against Muhammad’s own fort at Al Masnaah. Muhammad’s mother, who is unnamed in the papers, took charge of the fort’s defences. According to reports received by Aslan, when Shaikh Saud offered to liberate her son if she surrendered, Muhammad’s mother responded by firing a volley of cannon against him (IOR/F/4/1435/56726, f. 242v). Aided by reinforcements sent by Muzah, Muhammad’s mother was able to hold the fort. Although Sayyid Hilal joined Shaikh Saud’s attack, Aslan reports that both men had returned to their respective territories by the end of April (IOR/F/4/1435/56726, f. 262r).

Thus, it appears that the successful defence of the Imam’s territories in 1832 was led by women. These records within the IOR/F/4 Series files offer an insight into the intriguing character of Muzah, and the powerful position she held during her nephew’s long reign as Imam, as well as highlighting other women who successfully took up the reins of power. What these instances can tell us about the role of women in nineteenth-century Oman will be considered further in a forthcoming sister article.