Overview

Among the known Arabic manuscripts on astronomy, the large amount of texts about Ptolemy's Almagest contrasts with the very few preserved copies of the Almagest itself. Although this work had been available in Arabic since the early ninth century, in many cases more recent commentaries and reworkings replaced the need for reading Ptolemy's actual work. It was also in commentaries on the Almagest that Arabic astronomers and mathematicians between the ninth and the seventeenth centuries discussed their own contemporary concepts and ideas.

The Arrival of Ptolemaic Astronomy

As soon as the Almagest had been translated into Arabic in Baghdad in the early ninth century, Arabic-speaking scientists began critical work upon Ptolemy’s doctrines. One reason for this interest was the Arabs' simultaneous encounter with different astronomical systems, as Ptolemy's theories often contrasted with Sasanian and Indian traditions from the East. Furthermore, there were obvious discrepancies between the observed positions of celestial bodies in the time of the Islamic Empire and their predicted positions as calculated from Ptolemy's data – which by the ninth century was more than 600 years old. Inconsistencies in the sources incited Arabic-speaking astronomers not only to scrutinise but also to merge, supplement and update the inherited traditions. This process involved independent astronomical observations at newly built observatories, while Ptolemy's theories became a prominent subject in Arabic scientific literature.

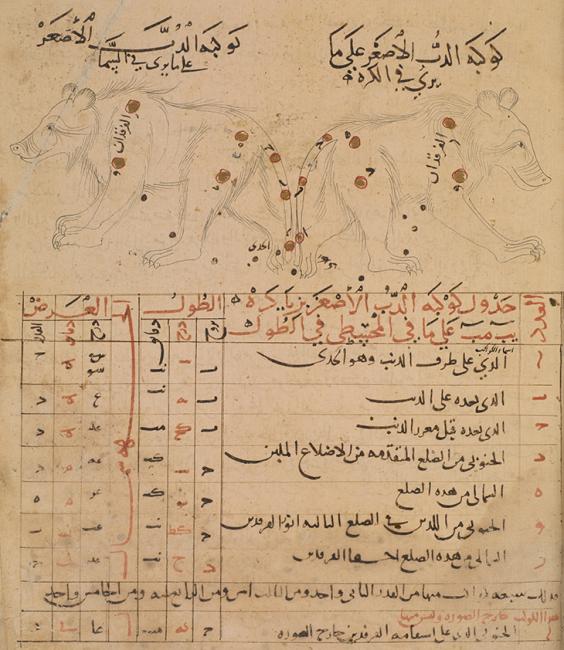

Improved observational data and advanced mathematics enabled Arabic-speaking astronomers to continuously refine Ptolemy's astronomical parameters and tables. Tables of astronomical, numerical data were collected in so-called Zījes which, though following Ptolemy's concepts, often appeared as self-contained works. At the same time, specialised treatises were written on particular Ptolemaic theorems, while other Arabic texts were explicitly devoted to the Almagest, in the form of commentaries and other reworkings. They included not only summaries and introductions, but also profound critiques and redactions of Ptolemy's work.

The Commentators

To date, approximately thirty Arabic commentators of the Almagest from the ninth to the seventeenth centuries have been identified from preserved parts of their works or through references in other texts. In many cases the names of the authors as well as their geographic and temporal origins are known. Nevertheless, the content of their writings, the sources and traditions on which they depend and the influence they had on later scholars are often known only in outline. Arabic recipients of the described treatises often annotated or reworked their copies of the texts or combined them with contents of different origins. As a result of this continued, creative reception, the variety of available versions and traditions increased considerably.

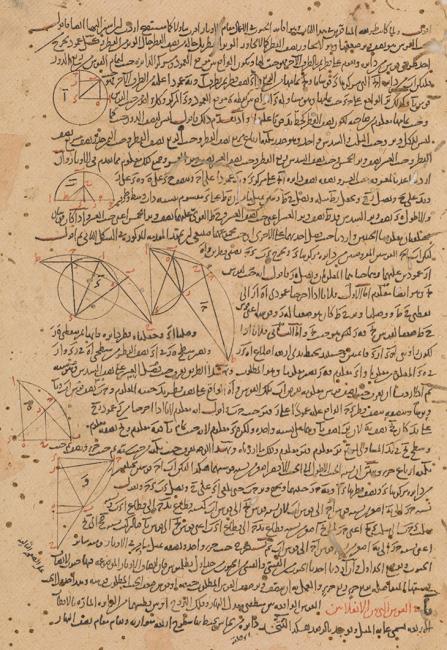

Prominent Arabic works on the Almagest comprise ‘Elementary Introductions’ (e.g., Tas-hīl al-Majisṭī by Thābit ibn Qurra in ninth century Baghdad) and ‘Summaries of the Almagest’ (Mukhtaṣar or Talkhīṣ al-Majisṭī, e.g., by al-Abharī in the second half of the thirteenth century). Such titles are distinctive of certain genres, as was also the case with ‘Doubts’ against Ptolemy (Shukūk, e.g., by al-Qabīṣī in the tenth century and Ibn al-Haytham in the early eleventh century) While the authors of ‘Doubts’ point at weaknesses in the Ptolemaic theory, other works intend to improve Ptolemy's theorems or their presentation in the Almagest. Famous examples of the latter kind are the ‘Correction of the Almagest’ (Iṣlāḥ al-Majisṭī) by Jābir ibn Aflaḥ from twelfth-century al-Andalus and the comprehensive ‘Redaction of the Almagest’ (Taḥrīr al-Majisṭī) by al-Tūsī from thirteenth century Maragha, in today's Iran.

The Significance of the Commentaries

Al-Tūsī's Redaction of the Almagest also shows the importance that certain commentaries had for the transmission of Ptolemy's ideas in the Arabic-speaking world. More than a hundred manuscripts of the work exist, which is about ten times as many as there are copies of the Almagest itself. Moreover, al-Tūsī's redaction itself attracted various other authors to write commentaries about it, such as Nīsābūrī in his Tafsīr/Sharḥ Taḥrīr al-Majisṭī. While such sequences of commentaries represent an ongoing scientific discourse and also a changing reception of Ptolemy, the Almagest continues to be seen as the foundation of those developments. In addition, the influence of Arabic commentators on the Almagest was not limited to the Arab world. Many of their works, such as the aforementioned treatises by Thābit ibn Qurra and Jābir ibn Aflaḥ, were translated, for example, into Latin, Hebrew or Sanskrit, and on occasions became more influential outside than within the Arab world.

Arabic-speaking commentators on the Almagest certainly contributed to securing the transmission of Ptolemy through the Middle Ages. More importantly, however, they represent a culture of astronomical research that revered its classical authorities but that was nevertheless open for debate and innovation. This understanding of astronomy had a decisive influence on the development of non-Ptolemaic theories, especially, in the works of European astronomers of the early-modern period.