Overview

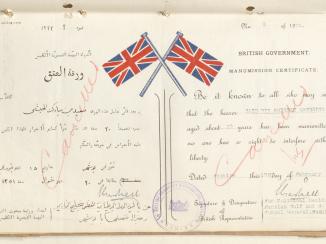

In August 1941 Britain and the Soviet Union invaded Iran. The invasion and subsequent occupation of neutral Iran was regarded by the governments of both countries as being vital to achieving victory over Nazi Germany in the Second World War. The occupation secured the Allies’ continued access both to Iranian oilfields, and to the so-called Persian Corridor, the Allies’ military supply line from the Gulf, through Iran, and into the Soviet Union. Although a Treaty of Alliance between the British and Soviet governments promised ‘to respect the territorial integrity, the sovereignty and the political independence of Iran’ (IOR/R/15/2/722, f. 32r), one of the first steps taken by the Allies as occupiers was to force the abdication of the Iranian monarch, Reza Shah Pahlavi.

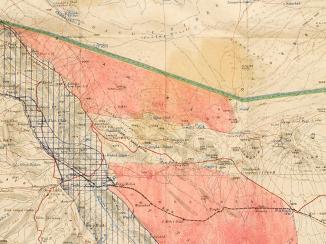

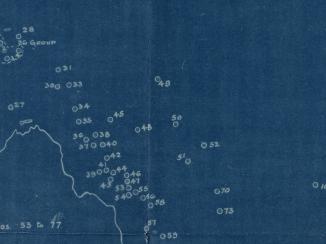

For the duration of the Anglo-Soviet occupation, Iran was split into two spheres of influence, with Britain controlling the southern, and the Soviet Union the northern half of the country. Both Britain and the Soviet Union embarked on propaganda programmes in an attempt to persuade Iranians that the occupation was in their own, as well as the Allies’ best interests. This would prove challenging, since Iran was in social, political, and economic turmoil, following failed harvests that had led to food shortages, malnutrition, and widespread poverty.

The Political and Secret files from the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. Records offer significant insight into Britain’s propaganda efforts in Iran, which sought to inspire the Iranian people’s cooperation both during and after the Second World War.

Early propaganda efforts

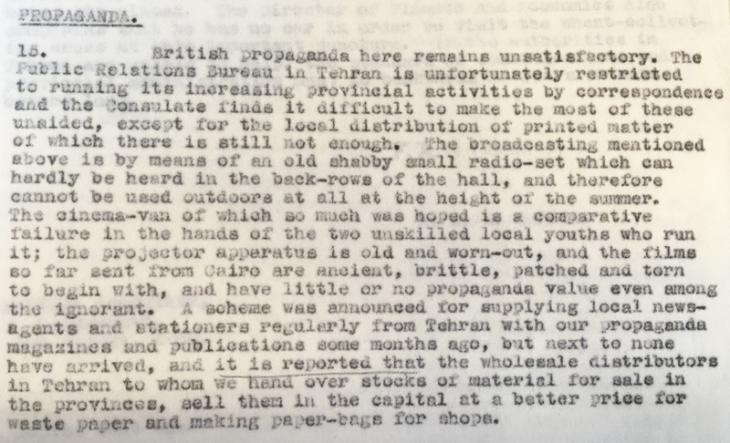

The records show that, early on in the occupation, a lack of resources hampered British propaganda efforts, which frequently lapsed into farce. For example, in September 1942, the British Consul at Kerman wrote that a ‘public radio would help to steady public opinion […] but the set is still awaited from Tehran’ (IOR/L/PS/12/3530, f. 18r). Meanwhile, the British Consul at Kermanshah reported in May and June 1942 that screenings of ‘ancient, brittle, patched and torn’ propaganda films by the region’s travelling cinema were ‘a comparative failure in the hands of the two unskilled local youths who run it’ (IOR/L/PS/12/3522, f. 40r), with performances ‘marred […] by hooliganism [and] the continual breakages of the old and unsuitable news-reel films’ (IOR/L/PS/12/3522, f. 34r).

The Consul at Kermanshah went on to complain that, despite plans to send propaganda magazines from the British Legation in Tehran, ‘next to none had arrived’, and he reported hearing that such publications were getting a ‘better price for waste paper and [for] making paper-bags for shops.’ Not long afterwards the cinema van ‘broke down completely’ (IOR/L/PS/12/3522, f. 45r).

By the beginning of March 1943, amid food shortages and widespread hunger, the Consul at Kermanshah conceded that there was a ‘good deal of anti-British talk’ in the province. He noted that although ‘educated Persian opinion’ supposedly preferred British over Soviet or German influence, the ‘poorer classes may incline towards [Communist] Russia’ (IOR/L/PS/12/3522, f. 85r). The Consul concluded that educated, middle-class Persians ‘would like to see British propaganda descending from its pedestal and catering more for the masses’.

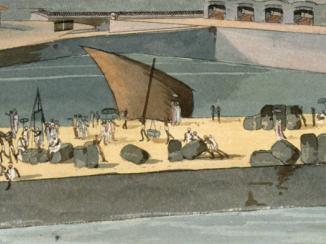

Humanitarian aid as propaganda

A stepping down from this pedestal had begun in May 1942, with a report written by Stephen Childs, Director of Britain’s Public Relations Bureau in Tehran. Childs recommended that British propaganda activities should be expanded to support hospitals, malaria prevention, and free food distribution to the poor. In August 1942 the Anglo-Iranian Relief Fund (also referred to as the Anglo-Persian Relief Fund) was founded with an initial investment of £10,000 from HM Government. Though a humanitarian effort, the Fund’s activities were listed under the heading of British propaganda in consular and intelligence reports. Another important benefit of the mobile dispensaries dispatched to deliver medical supplies to more remote parts of Iran was the opportunity they afforded to collect intelligence about tribes and tribal regions that could be of use to British officials at a later date.

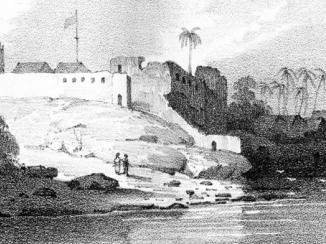

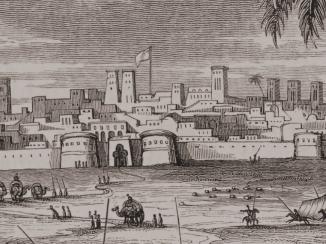

In October 1943 the Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. at Bushire (Bushehr) wrote that the ‘Anglo-Persian Relief Fund came to the rescue’ of a local sanatorium threatened with closure (IOR/L/PS/12/3713, f. 195r), and two months later the British Consul at Kermanshah reported that ‘the feeding of a limited number of poor and destitute, under the auspices of the Anglo-Iranian Relief Fund, began on January 1st […] Suitable newspaper publicity was given’ (IOR/L/PS/12/3522, f. 152r). Earlier that year, the British Minister at Tehran, Reader Bullard, had written to Secretary of State Anthony Eden confirming that ‘full publicity had been given to this [the Relief Fund’s] work in wireless broadcasts and in the press, and it has undoubtedly had a favourable influence on our popularity in some circles’.

Planning for post-war propaganda

By early 1944 the Allies’ fortunes had improved, and an eventual victory over the Axis powers was looking increasingly possible. British officials consequently began to turn their attention towards post-war Iran. In January 1944 the British Consul at Bushehr confided to his counterpart in Tehran: ‘I may say at once that I welcome any tendency in our propaganda to switch from the “win the war” topic to a general popularisation of British (which includes Indian) culture and commerce.’ Even before the fall of Nazi Germany, British officials had already returned their focus to empire building.