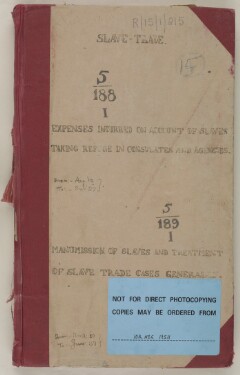

Overview

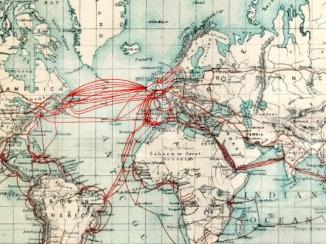

The forms of slavery that British officials encountered in Arabia and the Indian Ocean were very different from that which Britain had instituted for its own benefit in the Atlantic, where British ships transported slaves from Africa to the Americas for use in plantations growing commodities such as sugar and tobacco.

Social Rather Than Commercial Slavery

In Arabia and around the Gulf, the British encountered a form of slavery that was socially rather than commercially rooted in society. Though slaves here were recruited from as far afield as East and North Africa and the Asian subcontinent, they were generally integrated into the society they found themselves in. They were converted, often forcibly, to Islam and lived alongside the families they served. Many slaves were given their freedom in due course, an honourable act encouraged by the Quran. A higher proportion of slaves were women, compared to those in the American plantations. Most worked as domestic servants. Most of the male slaves worked in the region’s key economic industries: pearl fishing and date farming.

British Attempts to Suppress the Trade

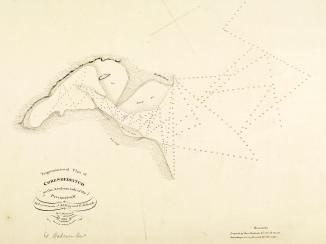

Suppression of the slave trade was one of the key justifications given by the British for taking control of the waters around the Arabian Peninsula, including the Gulf. For British officials, the transport of slaves by sea was part and parcel of the uncivilised nature of the region’s inhabitants. Punishing acts of piracy and eradicating the slave trade would help bring order to the region, and thus ensure the safety of Britain’s own ships and commercial trade routes through the western Indian Ocean to India.

Between 1860 and the 1890s, the British navy went to great lengths to restrict the slave trade between East Africa and Arabia. The British Government signed slave trade prohibition treaties with the Sultans of Zanzibar and Muscat, the Shah of Persia, and other rulers in the Gulf. However, British officials took no steps to involve themselves in the abolition of slavery. So, while the trade in slaves was outlawed, the ownership of slaves was not. In response, the proportion of Gulf slaves born into slavery (referred to as domestic slaves) grew in relation to the numbers of imported slaves.

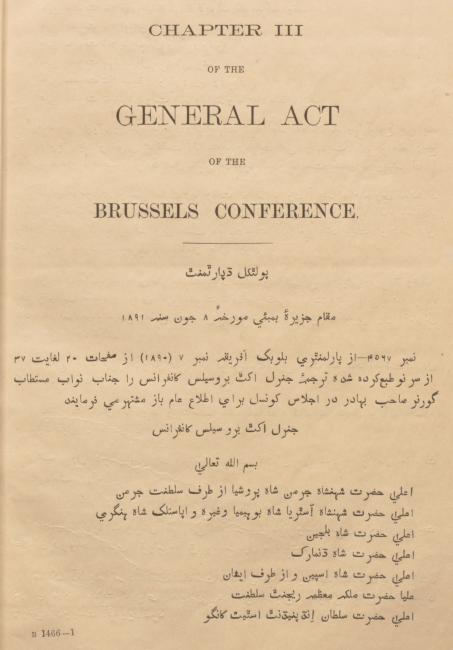

The suppression and abolition of slavery became an increasingly international concern from the late-nineteenth century onwards. The Brussels Conference General Act of 1890 advocated greater intervention by the European powers in the suppression of slavery in their imperial possessions. The League of Nations’ 1926 Slavery Convention sought the ‘complete elimination of slavery in all its forms’.

In the wake of growing international consensus on the slave trade, British officials in the Gulf faced two distinct problems. First, the pearl fisheries – the Gulf’s main source of income – were reliant to some degree on slave manpower. Second, domestic slavery was an accepted and integral aspect of life for the inhabitants of the region, and British officials were reluctant to become involved in disputes involving domestic slaves.

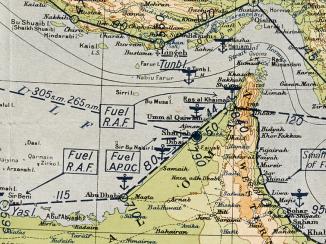

British Attempts to Mediate on Slavery

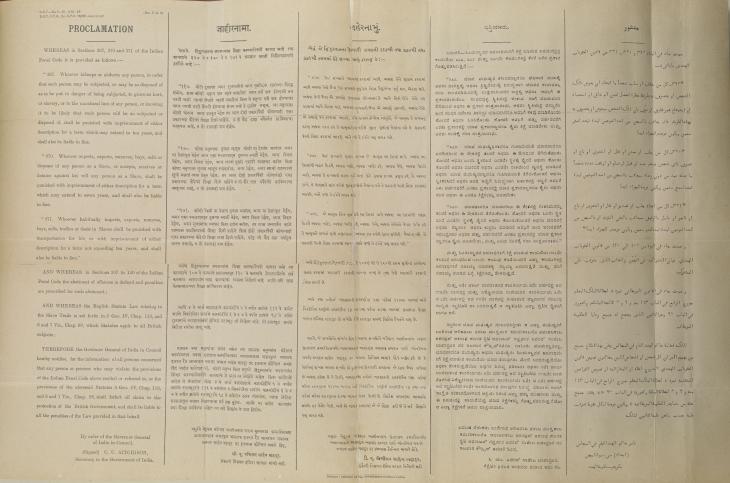

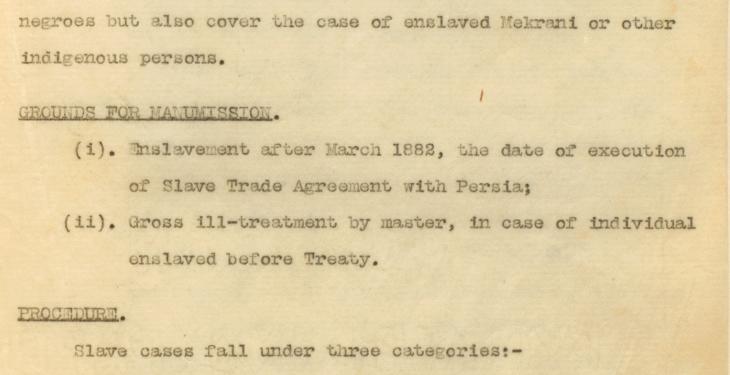

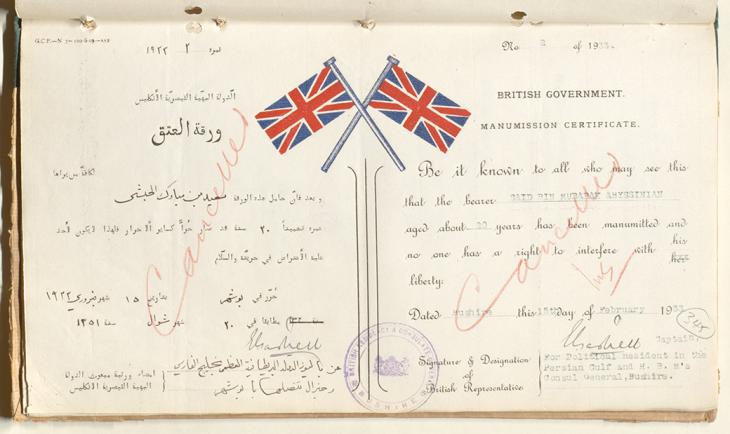

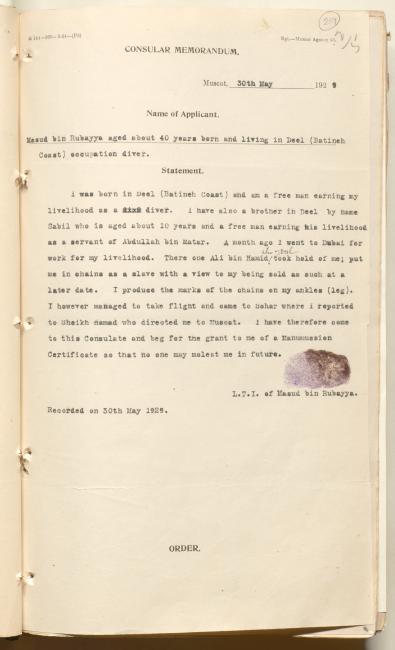

In 1912, Lieutenant-Colonel Percy Zachariah Cox, the Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. , devised a set of guidelines for manumission by which slaves, under certain circumstances, could be given their freedom by British officials. Applications for manumission were heard at the Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. in Bushire, the Political Agencies in Bahrain, Muscat and Kuwait, as well as by the Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. Agent at Sharjah. Slaves from those places where treaties had been signed with the British government, who had been enslaved after the date of the signed treaty, were considered to be illegally enslaved, and eligible for manumission. Slaves who had been enslaved before the signing of a treaty or who were domestic slaves, could not be manumitted, unless there was evidence of cruelty against them by their owners.

A manumission certificate was given to slaves whose request for freedom was granted, which was almost always the case. In practice however, the certificates were of little or no use in preventing individuals from being re-enslaved, as occasionally happened. But this did not prevent them being seen by many as important symbols of freedom – something which many slaves took great risks and travelled great distances to obtain.