Overview

Shaikh Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa was one of the most prominent figures in Bahrain during the first half of the twentieth century and, as such, is frequently mentioned in the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. Records. A number of key moments in his life are recorded in more detail.

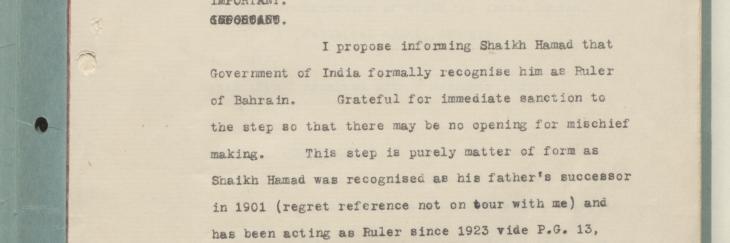

Hamad was formally recognised as the ruler of Bahrain in 1932, upon the death of his father, Shaikh Isa bin Ali Al Khalifa, however, he had been the de facto ruler of the country for almost a decade prior to his official succession.

Rupture in the Al Khalifa Family

In 1923, the British authorities had forced Isa to abdicate and installed Hamad as ruler in his place. The nature of Isa’s removal caused a serious rupture within the Al Khalifa family and thus Hamad was not officially named as ruler until Isa’s death nine years later.

Hamad was acknowledged as Isa’s heir apparent by the British Government in India in 1901 and afterwards grew close to the British authorities in Bahrain. After his installation as ruler in 1923, a series of administrative and institutional reforms – drafted by the British Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. in Bahrain, Clive Daly – were introduced in the country.

Reforms and British Influence

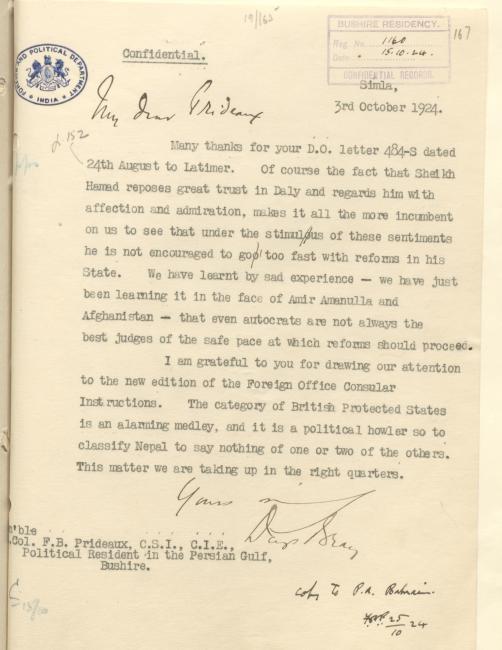

The reforms aimed to centralise and modernise the administration of Bahrain and curtail the persecution of the native Baharna population of Bahrain by members of the Al Khalifa family and their supporters. Hamad is said to have placed enormous trust in Daly and the closeness of their relationship caused the British Government in India to worry that Daly would pressure Hamad to go ‘too fast’ with the reforms.

Daly’s reforms threatened the position of many of the beneficiaries of the status quo in Bahrain including the nakhudas (the pearling boat owners), the Dawāsir tribesmen, some Sunni merchants and members of the Al Khalifa family itself. Unsurprisingly, Hamad’s role in enacting the reforms served to increase opposition towards him within Bahrain.

An Attempt on Hamad’s Life

Opposition grew to the extent that one evening in October 1926, while Hamad was driving to visit his wife, an attempt was made on his life. A number of shots were fired at his car as it went over a small bridge but the assailants’ shots missed and he escaped the attack unhurt.

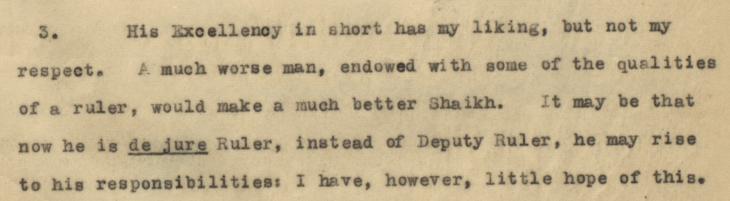

In 1932, Trenchard Craven Fowle, the British Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. , decried what he perceived to be Hamad’s lack of interest in ruling. In a letter to the British Government in India, Fowle observed that Hamad’s true (and only) passion appeared to be hawking and that ‘a much worse man, endowed with some of the qualities of a ruler, would make a much better Shaikh’. It was in Britain’s interest to have an active leader involved in the day-to-day running of the state, so long as they remained cooperative.

Official Visit to Britain

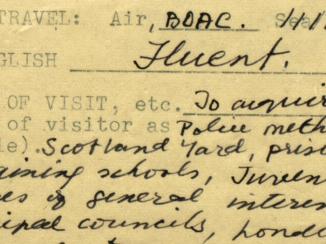

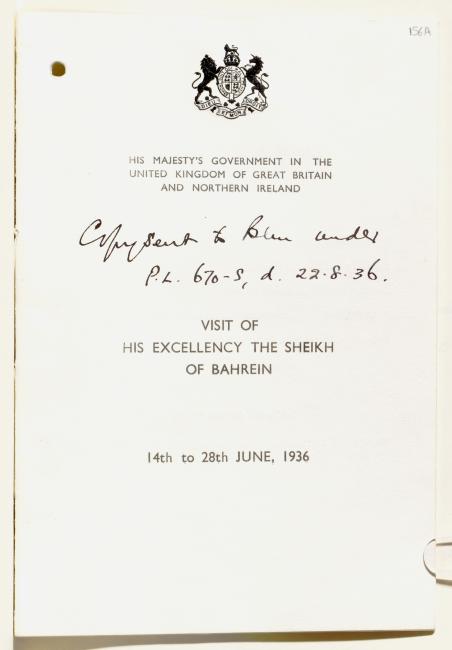

In 1936, Hamad made an official visit to Great Britain during which he met with King Edward VIII. Hamad also visited the Royal Military College at Sandhurst, the Royal Courts of Justice, the Zoological Gardens in London, attended the horse races at Ascot and even saw a play named ‘Please Teacher!’ at the London Hippodrome theatre.

Hamad suffered from diabetes and during this trip he also visited Britain’s leading medical authority on the illness and was proscribed a course of insulin treatment, which he continued upon his return to Bahrain.

As a result, Hamad was also given strict dietary rules to follow. However according to his long-serving personal adviser Charles Belgrave, after struggling to adapt his diet, his intake of insulin had to be increased to an abnormally large dose and his health began to seriously deteriorate.

In 1942, Hamad died after suffering a stroke. His son, Shaikh Salman bin Hamad Al Khalifa, succeeded him as ruler of Bahrain and asked Charles Belgrave to continue in his role as Adviser. A detailed account of Hamad’s death and funeral written by Belgrave – is contained in the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. Records.