Overview

Introduction

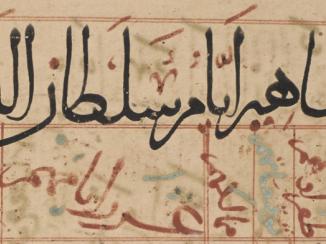

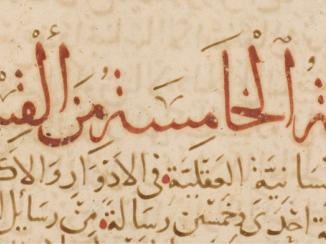

Four years after the accession of the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb (1027 AH/1618 CE-1118/1707; ruled from 1068/1658), a senior courtier entitled Diyānat Khān commissioned a manuscript compilation of fourteen Arabic and Persian texts on music theory.

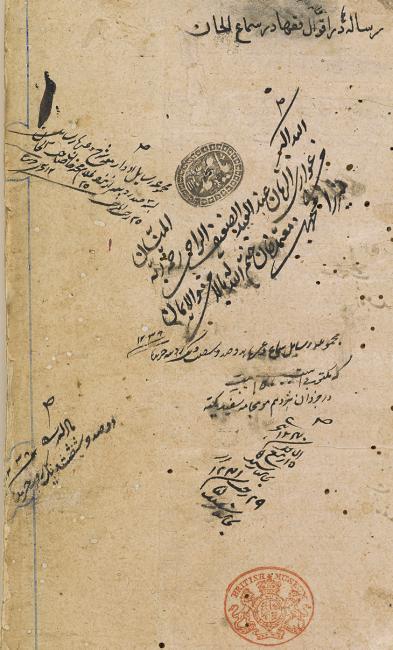

Now held at the British Library as Or. 2361, this manuscript is first and foremost a bilingual handbook of important reference works on the scientific analysis of sound, rhythm, harmony, and instrument-making. Additionally, however, it also contains a remarkable quantity of internal evidence testifying to its particular context of production within the peripatetic Mughal court.

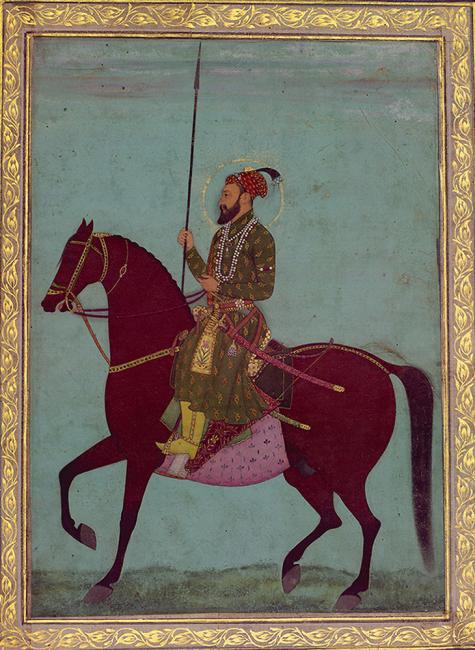

Diyānat Khān: servant of Aurangzeb

Diyānat Khān (Shāh Qubād ʻAbd al-Jalīl al-Ḥārithī al-Badakhshī, d. 1083/1672) was a military commander and scholar. According to his grandson, a historian who later inherited Or. 2361, he was born in Qandahar but grew up in India. He eventually rose to prominence, becoming Aurangzeb’s governor of the Deccan at Aurangabad. Complementing his interest in Arab-Persian musicological heritage, he also commissioned copies of texts on contemporary Indian instrumentation and performance, as well as on other scientific subjects.

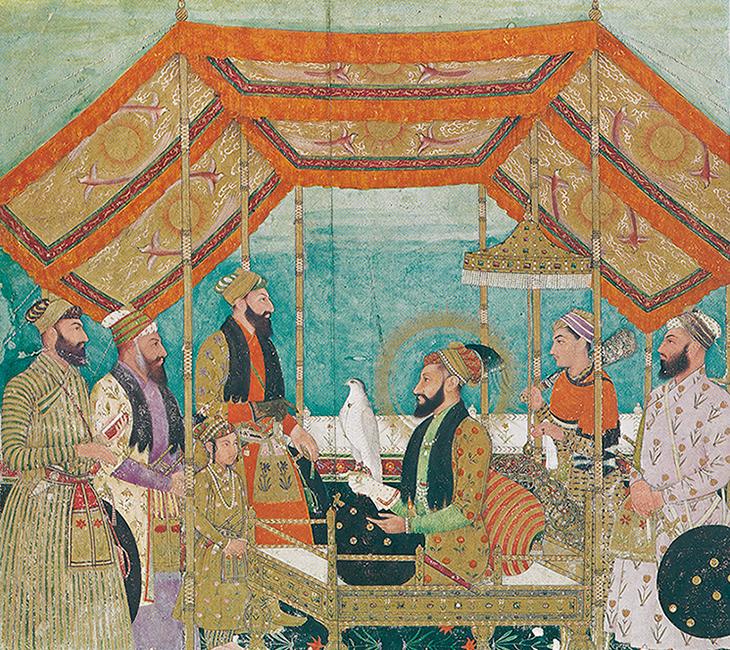

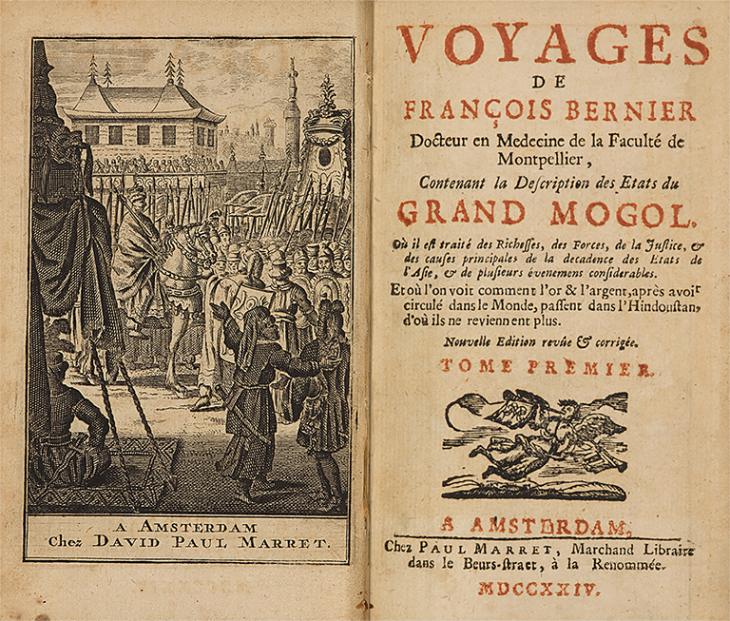

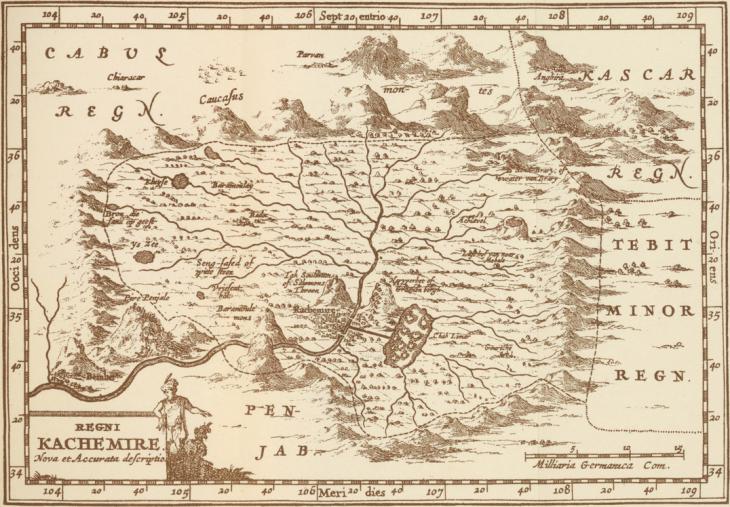

In 1073/1662-3, Diyānat Khān’s duties included joining the imperial court in its journey from Shāhjahānābād (Delhi) to Kashmir via Lahore. The journey is documented in the Maʾāsir-i ʿĀlamgīrī, an account based on Mughal court chronicles, and the grand procession was described by one participant, the French traveller François Bernier.

Bernier vividly details the complexity of the organisation and the throngs of people who joined this long and difficult expedition. These included the whole nobility of Delhi, each with their own grand tent, the ladies of the court, the army, and all the attendant servants, porters, aides-de-camp, and beasts of burden including camels, mules, and elephants.

While neither Bernier nor Maʾāsir-i ʿĀlamgīrī mention it, the colophons of Or. 2361 inform us that among all this travelled Diyānat Khān, his entourage, scribes, and this unfinished musical manuscript.

A mobile manuscript: begun in Delhi…

The process of Or. 2361’s creation can be reconstructed from its detailed colophons. Colophons are short statements found at the end of a text, recording information such as when and where the text was copied and sometimes later checked, and by whom. While this practice is common in Arabic and Persian manuscript traditions, Or. 2361 is particularly rich in detail thanks to its large number of texts, and the close attention paid to the work by its patron, Diyānat Khān.

The book was started in Ṣafar 1073/September 1662, ahead of Aurangzeb’s departure from Delhi, with two Persian treatises on the lawfulness of music and singing, copied back-to-back by a Persian-language scribe, Muḥammad Amīn of Akbarābād (today’s Agra).

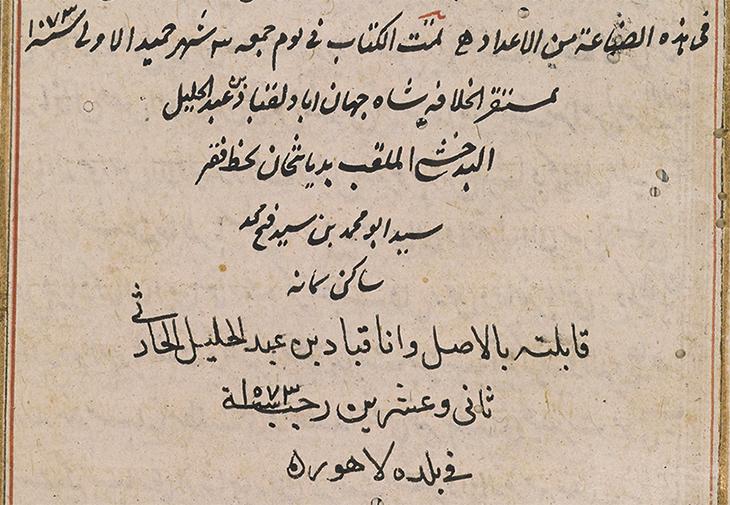

Shortly thereafter, the first six of Or. 2361’s nine Arabic texts were copied during the four weeks from 17 Rabī‘ I/29 November to 13 Jumādá I/24 December. These were a treatise by the early Islamic philosopher, al-Kindī (d. 256/873), which is today the only surviving copy, a work by the Abbasid courtier-scholar Ibn al-Munajjim (d. 300/912) on the traditional Arabic musical modes, further texts by the scholars al-Shirwānī (d. c. 857/1453), Ibn Zaylah (d. 440/1048-9), and al-Fārābī (d. c. 339/950), and an anonymous commentary on an important seventh/thirteenth-century musicological treatise, the Book of Cycles (Kitāb al-Adwār) by al-Urmawī (d. 693/1294). These were all transcribed by the scribe Sayyid Abū Muḥammad ibn Sayyid Fatḥ Muḥammad Samānī (or Samāna’ī), of the Punjabi town of Samana. Other colophons in the manuscript, and the consistency of handwriting throughout, indicate that all the texts within Or. 2361 were written by either Samānī or Muḥammad Amīn alone, specialising in Arabic and Persian respectively.

… continued in Ambala and Lahore…

Aurangzeb and his entourage left Delhi on 7 Jumādá I 1073/18 December 1662. By the end of the following month, the seventh of the Arabic texts (another commentary on the Kitāb al-Adwār) and the third of the Persian ones (extracts from a work by Ibn Sīnā, d. 427/1037) had been completed at Anbālah (modern Ambala), a fortified town famous for its pleasure gardens, almost half-way to Lahore. After taking a leisurely route, hunting and managing affairs of state along the way, Aurangzeb and his companions reached Lahore on 10 Rajab/18 February and stayed until 3 Shawwāl/11 May, awaiting the melting of snow on the mountain passes.

It was during the halt in Lahore that Diyānat Khān’s active involvement in checking the copy began. The colophon Section at the end of a manuscript text. to al-Shirwānī’s treatise records that he personally checked the text ‘in the vicinity of Lahore’, completing this task on 9 Rajab/17 February. Days later, he also checked the work by al-Fārābī. Meanwhile, Samānī was producing a copy of the original text of Kitab al-Adwar, which was completed on 3 Ramaḍān/11 April in Lahore.

Most camp followers did not continue to Kashmir due to the difficulties of traversing the mountain passes. Thus, when Aurangzeb left Lahore, Diyānat Khān took his half-finished manuscript with him but apparently not the scribes, whose whereabouts are unknown until the following year in Delhi when further texts were copied for the manuscript.

Bernier evokes the trials of the journey: the heat of the Punjab, hazardous river crossings by pontoon, and perilous mountain ascents, including a terrible accident which killed several people and elephants and caused Aurangzeb never again to visit Kashmir. By Dhū al-Qa’dah/June, the royal party had arrived at Srinagar, then called ‘Kashmir Town’ (Baladat Kashmīr), and Bernier describes the relief occasioned by the temperate beauty of the landscape.

… and reviewed in Kashmir

Whilst in Srinagar, Diyānat Khān worked on his manuscript alongside serving the emperor, completing the checking of the two commentaries on Kitab al-Adwār (one of which was also checked against another authoritative copy four years later) and the works by Ibn Zaylah and Ibn al-Munajjim. Diyānat Khān only checked Arabic texts, perhaps indicating a greater written literacy in Arabic than in Persian, the language spoken at court.

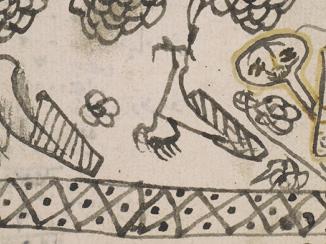

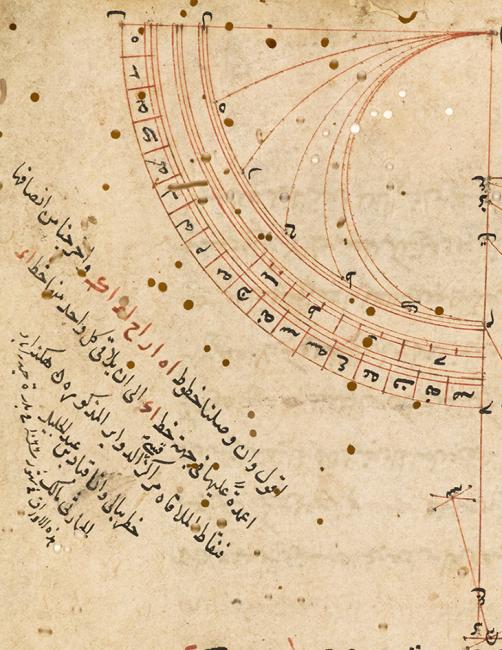

Diyānat Khān’s involvement may well have gone beyond checking the texts: it is known that he himself added diagrams to another manuscript commissioned for him, a process requiring significant skill and understanding. It is possible that he was also responsible for the many diagrams in Or. 2361.

After nearly three months of business and pleasure, Aurangzeb left Kashmir on 22 Muḥarram 1074/26 August 1663, but it was not until 23 Rabī‘ I 1075/14 October 1664, in Delhi, that any further texts were added to the manuscript, when Samānī transcribed a supercommentary (ḥāshiyah) on a treatise by al-Khujandī (fl. 702/1303-715/1316). Two final Persian works were completed by 12 Rajab 1075/29 January 1665. They were checked against the originals soon after their copying, and in one case, again after a few years when another copy of the source text was located.

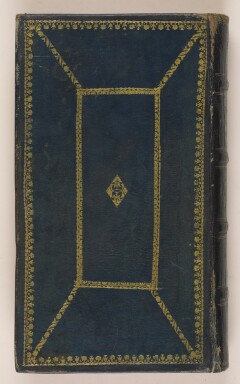

The afterlife of Or. 2361

The codex A collection of pages, usually gathered into quires, and bound between covers. as it is today poses some conundrums. The present order of the texts does not follow any consistent system, whether by date of composition, copying, language, or subject matter. It was evidently written piecemeal and bound together, but the original order is unknown. Finally, the manuscript’s Kashmiri-style illumination and gold-tooled blue leather binding date from a later period, likely connected with a series of rapid transfers of ownership in the nineteenth century. The original manuscript would have been a sober, scholarly affair.

With such a wealth of internal information, Or. 2361’s significance goes well beyond its musical subject-matter, providing a snapshot of the sometimes highly mobile context of manuscript production at the time. The pages of this volume trace the interconnecting lives of the emperor Aurangzeb, his intellectual courtier Diyānat Khān, and the latter’s two scribes over a few years, against a moving backdrop of cities, mountains, plains, and royal encampments. A scholarly life was evidently not a sedentary one for Diyānat Khān.