Overview

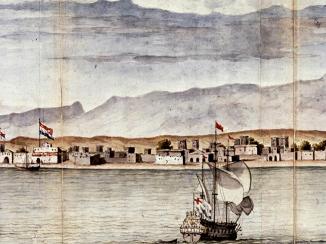

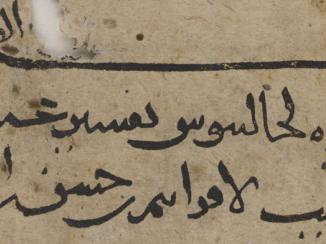

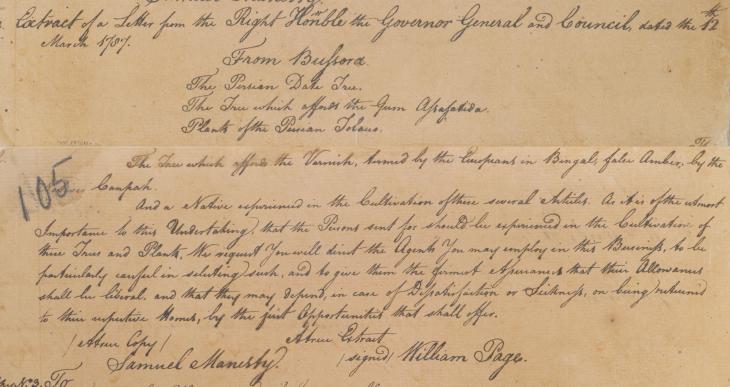

One day in October 1787, with the strengthening north-westerly winds blowing an occasional frenzy through Bushire’s date palms and an agitated sea breaking against the fortress walls, Edward Galley, East India Company (EIC) Resident, opened and read a letter that had just arrived from Basra. Contained within was a list of plants, six in all.

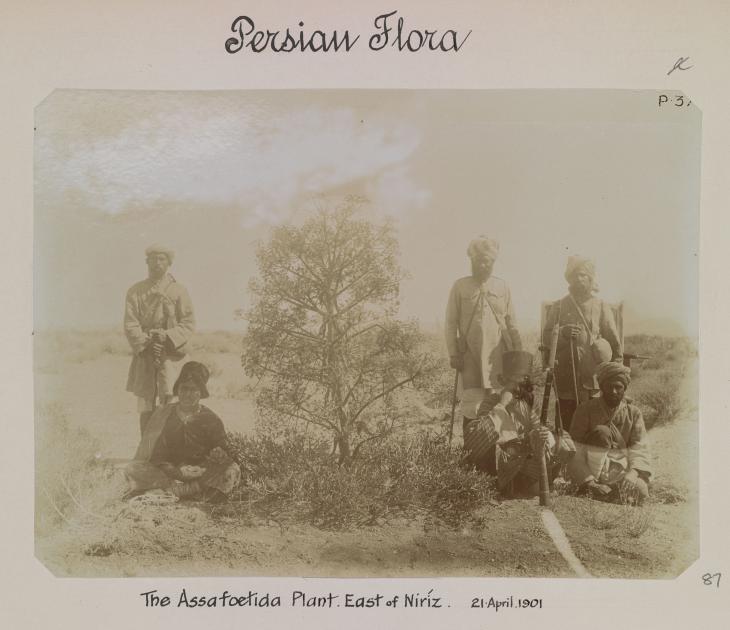

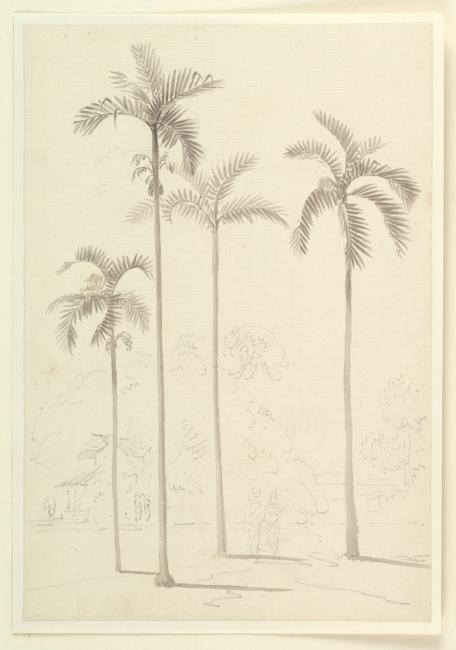

Some were obvious; the ‘Bussora Date Tree’ was unmistakeable and the ‘famous Persian Tobacco’ was as well-known as described. But others were a little harder to pin down for those with little botanical knowledge, such as the ‘Tree which produces Gum Assafatida’ or the ‘Tree which produces the Varnish Gum’.

A botanical garden had recently been set up in Kolkata and these were the species, believed to grow in the Gulf region, that were wanted for this new enterprise. Specimens would have to be found, collected and shipped back to India.

To Galley, this may not have meant a great deal; this was part of the everyday business of running the Factory An East India Company trading post. at Bushire. Looking at these letters today, however, it is possible to see that they were part of a Company venture that would draw the Gulf into a larger project aimed at gaining a deeper and more complete understanding of the natural world.

The Botanic Garden

The idea for a botanical garden was first tabled in the summer of 1786 by Robert Kyd, an officer in the Indian Army, as a potential safeguard against famine. But it soon became something much bigger and more ambitious. In a letter dated 20 November 1787, Kyd sets out his vision for the garden to be part of the wider pursuit of scientific knowledge, recognising the usefulness this stock of information may prove in ‘enlightening future Administrations on many objects now imperfectly ascertained’

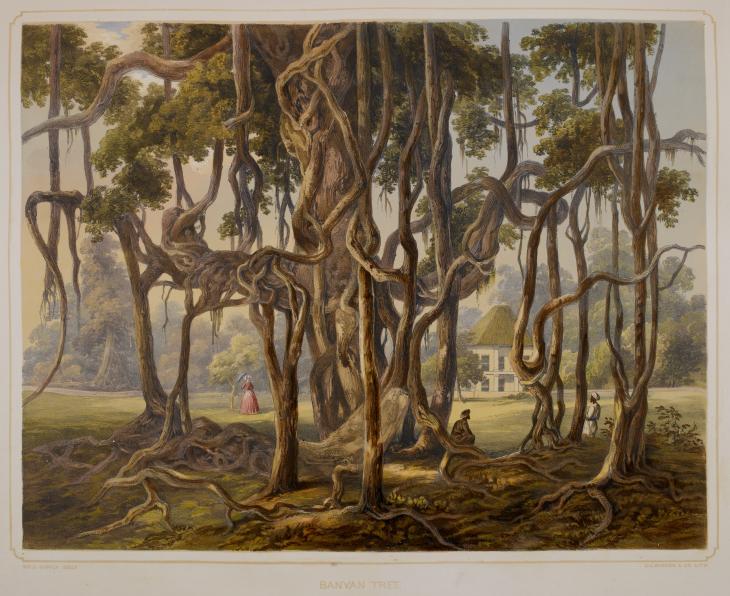

Specimens were collected not only from all over India; but also from many other parts of the world where the British had a presence. Plants from China, Burma, Indonesia, Europe and, of course, Arabia and Persia all found their way into the garden. Those of economic value were prioritised – teak, the sago palm and various spices, for example. The tea industries of Assam and the Himalaya owe their existence largely to the importation of the plant into the garden from China.

‘The Fund of General Knowledge’

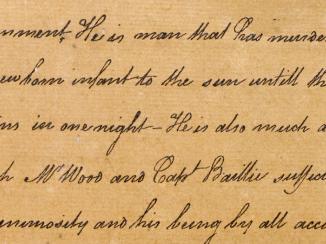

At this time, the expansion of European scientific thought and practice was gathering pace, and was thus far facilitated mostly through an informal network of individuals. To spend one’s spare time investigating aspects of the local surroundings, including flora, fauna, geology, and local custom, was considered a ‘gentlemanly pursuit’, and was practiced by Company servants and merchant adventurers at a newly global level.

This knowledge was consolidated by prolific correspondence between those who gathered it and would eventually become institutionalised in the shape of organisations such as the Asiatick Society (established 1784, later: The Asiatic Society of Bengal).

Only gradually did the EIC begin to actively support such ventures. The botanical garden in Bengal was one of the first instances of this support and it made the Gulf a part of an expanding European scientific enquiry that Kyd hoped might ‘add to the Fund of General Knowledge’.

William Francklin’s Mission in Persia

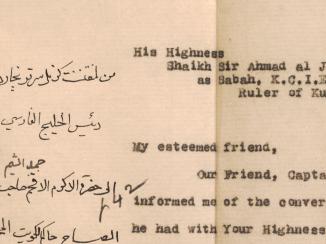

The Resident at Basra, Samuel Manesty, believed that some of the plants requested could be found in Persia, and on 7 December 1787 he wrote to Charles Watkins, the new Resident at Bushire, wishing William Francklin success on his journey to Shiraz to try and obtain them.

Francklin, funded by the Company and an archetypal gentleman scholar, spent eight months living with a Persian family in Shiraz where he learned the language and more about local customs than had hitherto been known. He went on to enjoy a considerable reputation as an orientalist and became a member of the council of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (founded 1823). Despite these achievements, his mission to procure plants for the botanical garden in Bengal does not seem to have been a success.

The evidence suggests that, of those species listed in the letter to Galley, only the date palm made it to Kolkata. In a letter to the Governor-General at Fort William, Manesty promises to send six of the trees, both male and female. Indeed, in an inventory of the garden of November 1790, nine date palms are listed. Just under a year later there were fifteen trees.

The garden itself remains and is now known as the Acharya Jagadish Chandra Bose Indian Botanic Garden. The original date palms have probably since been supplanted, but the letter requesting them still stands out within the records of the Bushire Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. , a rare indication of a Company ambition that was more than purely commercial or political.