Overview

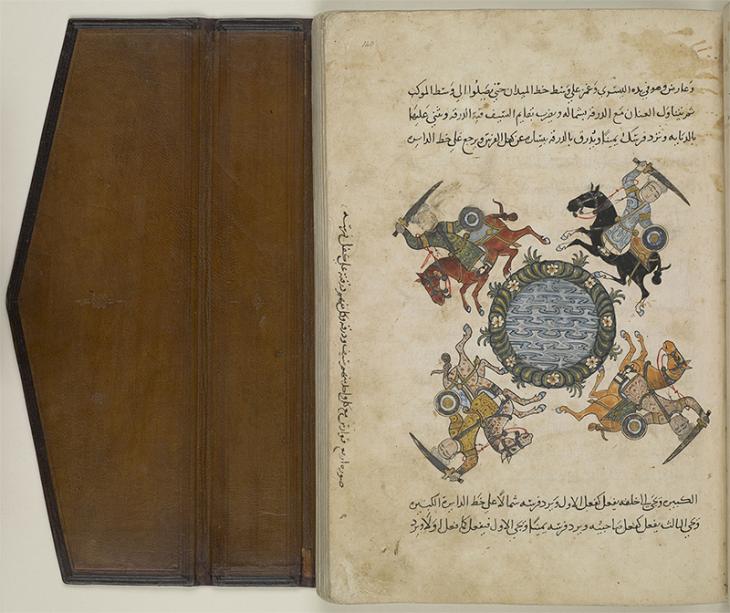

This strikingly illustrated manuscript on the subject of horsemanship was authored by Muḥammad ibn ‘Īsá ibn Ismā‘īl al-Aqṣarā’ī and completed on 10 Muḥarram 773 AH (25 July AD 1371). The manuscript’s title claimed that, in its comprehensiveness, it could nullify all desire for further instruction in the subject.

Entitled Nihāyat al-su'l wa-al-umnīyah fī ta‘līm al-furūsīyah it probably originates from Egypt or Syria. Over six hundred years later it lies within the British Library collections.

Whilst origin can often be discerned, the trail of provenance is often largely unknown. So how can we begin to trace the journey of a manuscript from its date of creation onto the British Library shelves?

The First Known Owner: Sir Thomas Reade

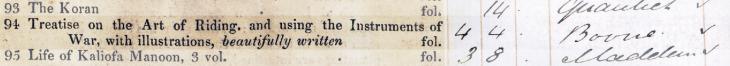

The British Library’s ‘Register of Additional Manuscripts’ states that this item was purchased from the estate of Sir Thomas Reade via a sale at Sotheby’s auction house. It is listed in the 1852 Sale Catalogue as Lot 94, a ‘Treatise on the Art of Riding and using the Instruments of War, with illustrations, beautifully written’.

The manuscript was the third most expensive item of the two-hundred and sixty lots from his estate, and by far the most expensive of Reade’s Arabic manuscripts. It was purchased on behalf of the British Museum for four pounds, four shillings (equating to four guineas, or £4.20 – about £500 today) by the brothers Thomas and William Boone, specialist antiquarian booksellers with whom the British Museum dealt in the nineteenth century. Prior to this, provenance can be surmised through tracing the life of its former owner.

Reade in the Army

Sir Thomas Reade (1782–1849) was born in Congleton, England. In 1799, at the age of sixteen, he ran away from home to enlist in the army. Following campaigns in Holland, Egypt and America, as well as postings across the Continent, Reade received many subsequent honours and promotions, culminating in his Knighthood in 1815, aged just thirty-three. This event coincided with the end of his military career and marked a turning point in his life, for, on 29 January 1816, Reade set sail with Sir Hudson Lowe for the remote island of St Helena in the South Atlantic.

Napoleon’s Jailer

According to a biography written by his descendant Aleyn Reade, Sir Thomas was deployed as Deputy Adjutant-General of the troops. Not only was he jailer to the French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte – exiled there after the Battle of Waterloo – but he acted as the main intermediary between Napoleon and Lowe, whose relationship was famously strained.

Whilst Count Montholon (who accompanied Napoleon to St Helena and was later suspected by some to have poisoned him) spoke favourably of Reade, as did Lieutenant Clifford (a Naval officer who visited the island in 1817), he was not popular with everyone. Gorrequer, Lowe’s Aide-de-camp and acting military secretary, referred to him in his diary by various derogatory pseudonyms including ‘Nincumpoop’ and ‘Ninny’.

In spite of the rumours and controversy regarding Lowe’s alleged ill treatment of Napoleon, Aleyn Reade argues that the exiled Emperor appeared to have liked or at least favoured Sir Thomas.

Life in Tunisia

Following Napoleon’s death in 1821, Reade returned to England and married Agnes Clogg. He remained there until 1824 when he was appointed Consul-General of Tunis. In addition to his main charge of defending against the French, his most notable achievement came in 1842 when he successfully influenced the Bey (monarch) of Tunis to abolish slavery throughout his dominions.

Reade remained in Tunis until his death from cancer in 1849 and was honoured with an impressive public funeral, which, as his obituary states, was ‘celebrated with solemnity and pomp’. It was Reade’s professional standing and foreign postings that enabled him to collect manuscripts, but the life he led outside of his official duties sheds more light on why he acquired them.

Reade the Collector

Like many high-ranking British officers of his day Reade was also a scholar and antiquarian. He studied and collected Carthaginian and Romano-African antiquities and zoological specimens, published papers and excavated among the ruins at Carthage at his own considerable expense. Many of the artefacts he unearthed were given to the British Museum, a practice that was common at the time, but would be a complicated diplomatic issue today. This was part of the less official, but equally destructive looting by colonial officials of the treasures of the greater empire. It is very probable that Reade acquired possession of al-Aqṣarā’ī’s manuscript at this stage of his career.

Unfortunately, this is where the trail runs cold. Exactly where, when and from whom Reade obtained this striking volume is unlikely to come to light. However, the personal interest of a high profile official in ancient antiquities allows us a small insight into the manuscript’s path to the British Library, where it now forms one of the highlights of the collection.