Overview

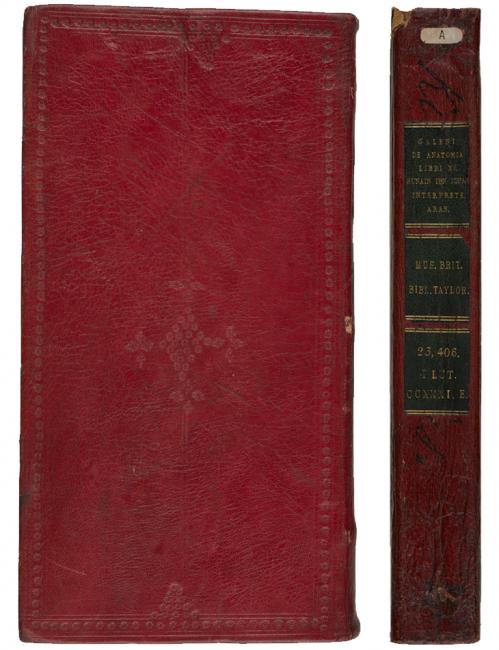

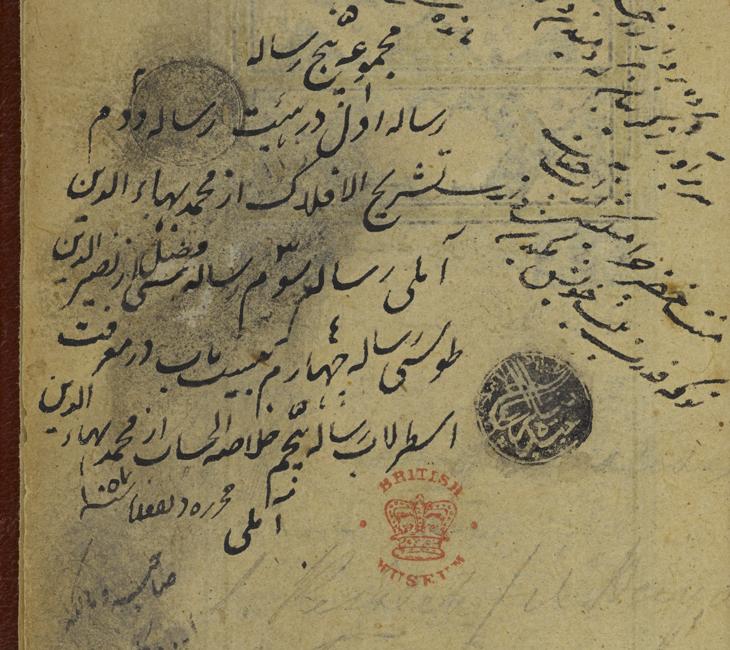

A group of manuscripts known as the Taylor Collection was acquired by the British Museum in the 1850s and 1860s. They all share a distinctive red leather binding, and many also bear a seal in Arabic script that reads ‘Abduhu Taylor’ (‘His servant, Taylor’). The Collection provides a rare connection between the British Library’s India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. Records and the Library’s outstanding collection of Arabic manuscripts.

Provenance

In April 1860 the British Museum Register of Additional Manuscripts recorded that 355 manuscripts in Turkish, Persian, and Arabic had been purchased for £2000 from a Mrs Taylor ‘by […] Capt. H. B. Lynch’ (Add MS 23252-23606). By itself, ‘Mrs Taylor’ would have been a difficult individual to trace, but the Preface of the 1894 Supplement to the Catalogue of the Arabic Manuscripts refers to a collection described in the old (Latin) Catalogue as belonging to a Lieutenant Colonel Robert Taylor (1788-1852), former British Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. and Consul of the East India Company at Baghdad.

Robert Taylor

According to a brief memoir written by his son-in-law, Thomas Kerr Lynch, Taylor showed a proficiency in classical studies, and after departing for India as a cadet in 1803, he obtained a leave of absence in 1805 to travel to Bushehr ‘for the special purpose of studying [the] Arabic and Persian languages’. He studied under the celebrated scholar Sayyid Ibrahim and became accomplished in both Arabic and Persian. In 1808 he was sent to Bombay (Mumbai), but returned briefly to the Gulf in 1809 following news that the British vessel Minerva had been “captured by boarders from a number of Qāsimī One of the ruling families of the United Arab Emirates; also used to refer to a confederation of seafaring Arabs led by the Qāsimī tribe from Ras al Khaima. boats” (IOR/R/15/1/729, f.11v). Most of those on board were slain, but his wife and son were spared, sold, and then ransomed for $MTT 1000 (the Maria Theresa thaler, then common currency throughout the Arab world) by the Resident at Bushire (Bushehr).

Following a number of other assignments in Bombay, Taylor was appointed Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. in Bussorah (Basra) in 1819. There he resumed his studies, and was in a position to collect manuscripts in earnest. He was made Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. at Baghdad in 1821 (not 1828 as stated by Lynch), and remained there until his dramatic downfall at the age of fifty-five.

Scandal and dismissal

J.P. Parry argues that one of the reasons for Taylor’s downfall was nepotism; he was seen to promote the commercial interests (especially in steam navigation) of his brother James and son-in-law Thomas Lynch over the principles of trustworthiness and even-handedness supposedly espoused by the British government. By making use of his official powers to assist his relatives – often financially – Taylor fell out of favour and was abruptly sacked in 1843. He returned to England and later died in Boulogne in 1852.

Personal Life

Colonel Taylor appears to have led an adventurous life and is described by McLeod Easton as an ‘almost mythical figure’. While Reade states that he was reputed to have married into the Persian royal family, McLeod Easton’s version is more scandalous: he claims that Taylor abducted and married a twelve year-old relative of the Shah against the wishes of the Persian royal family, although the Shah nevertheless reportedly met her while on a state visit to London in 1873. Taylor is known to have married an Armenian Persian woman named Rosa Moscow, who died in London on 15 July 1877, but the story about the ‘abduction’ is possibly an exaggeration of family legend. While Rosa would probably have been a teenager at the time of their marriage, this was not unusual in the nineteenth century.

Antiquarian Interests

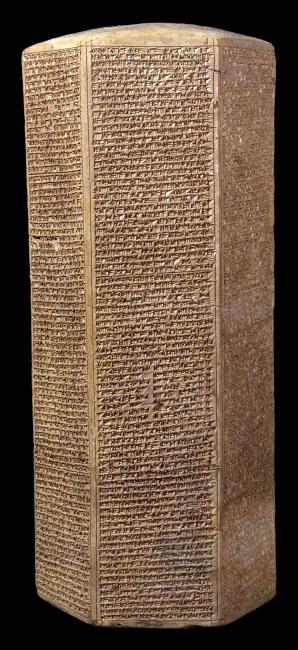

Aside from his professional career, and in common with many British officers abroad, Taylor was also an amateur antiquarian. In addition to collecting manuscripts, he was reputed to have discovered (or as Mitchell reports, possibly purchased) King Sennacherib’s prism, also known as the Taylor Prism, while excavating the ruins of the ancient Assyrian city of Nineveh.

The prism was an ‘important foundation document’ recording the deeds of King Sennacherib, and was instrumental in the decipherment of the cuneiform script. The British Museum website states that the prism was purchased from his widow in 1855, and was among other items from Taylor’s Collection that were sold after his death.

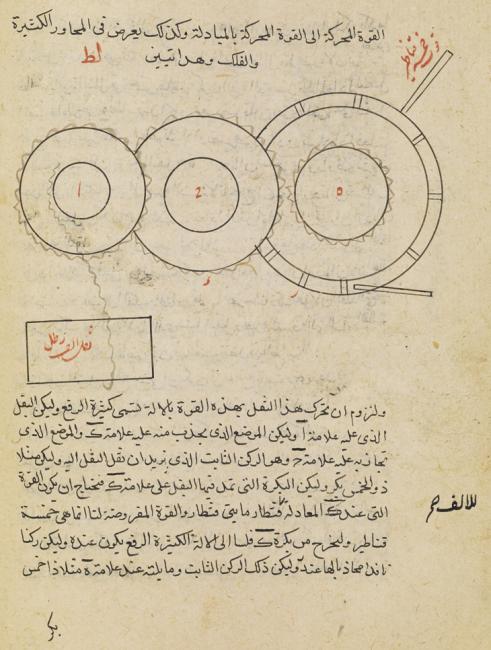

The Taylor Collection

The focus of Colonel Taylor’s unrivalled collection of Arabic and Persian books and manuscripts was on science and geography, and Reade notes that he was known to have opened up his private library to visitors. These included Henry Rawlinson, Taylor’s successor as Agent in Baghdad, as well as a prominent explorer, diplomat, and publicist credited with deciphering the Assyrian cuneiform script, and Henry Layard, excavator of Nimrud and Nineveh and later Ambassador to Constantinople (Istanbul). It is therefore not entirely surprising that most of Taylor’s manuscript collection ended up at the British Museum Library, where it formed the nucleus of its Arabic-language collection.