Overview

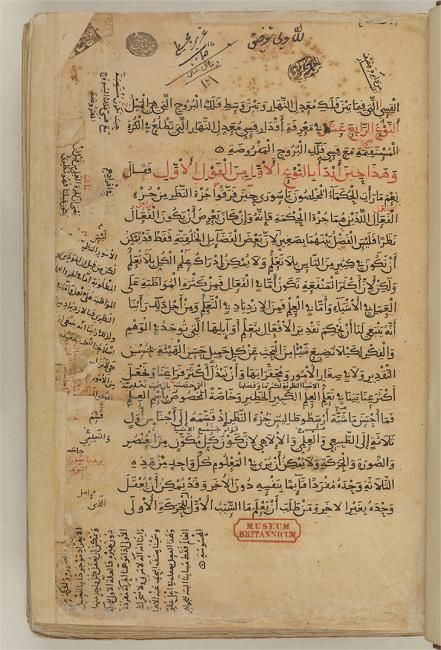

During the 8th to 10th centuries almost all Greek scientific and philosophical texts then available in manuscripts were translated into Arabic, and translation efforts continued into the following few centuries. The translators who carried out this work were not from a single community, and came from many ethnic and religious backgrounds. Important translators were Muslims like al-Ḥajjaj ibn Yūsuf ibn Maṭar (AD 786–830) and al-‘Abbās ibn Sa‘īd al-Jawharī (d. after 843), and even planet-worshipping Ṣābi’ans like Thābit ibn Qurrah al-Ḥarrānī (d. 901). But Christians made up a very large proportion of these translators. Why was that?

It seems to be due to the types of education particular to the various Christian communities within the Islamic world, and also due to the new religious and political situation that prevailed following the Arab conquests of the Middle East and North Africa during the 7th century.

Syriac-speaking Communities

Syriac is a dialect of Aramaic, an ancient Semitic language, indigenous to the region around the city of Edessa (now Şanlıurfa in southern Turkey), which was a major seat of Christianity during the centuries preceding the Arab conquests. Large numbers of Christians in the Byzantine Near East spoke Syriac and used it in their prayers and church services.

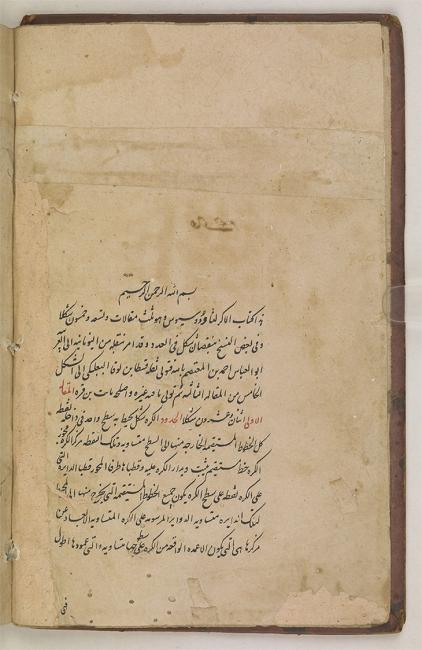

Christians in these Syriac-speaking communities received their education in monastic schools, where they studied in Syriac, but were also taught Greek, the original language of the New Testament. Moreover, there is good evidence that more advanced schooling in these Syriac Christian communities involved the study of ancient Greek books of science and philosophy, and many of these books were translated into Syriac.

Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq, a Christian Arab Translator

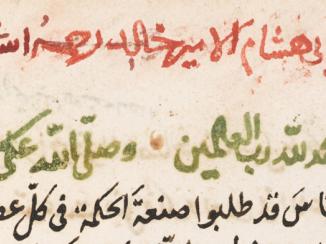

Perhaps the most important and prolific of these Syriac-speaking Christian translators was Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq (AD 809–73). Ḥunayn was a Nestorian Christian Arab, who probably spoke Arabic as his mother-tongue. He was schooled in Syriac from his childhood, conversed with his fellow Christians in that language and had learned ancient Greek to an extremely high level of proficiency.

Furthermore, Ḥunayn was one of the greatest physicians of his day, who systematised the writings of the Greek physicians and wrote his own original treatises, excelling in ophthalmology. So great was his fame as a physician that he became court physician to the caliph al-Mutawakkil (reg. AD 847–61). Ḥunayn is best remembered for translating all the available writings of the two fundamental Greek physicians Hippocrates (c. fifth century BC) and Galen (c. AD 129–c. 216) into Syriac and Arabic.

This was no mean feat since Galen’s writings make up a huge proportion of surviving ancient Greek literature. Galen was one of the most prolific authors who has ever lived, and his writings form about ten percent of all the ancient Greek books that still survive today.

New Possibilities for the Transmission of Knowledge

The combination of familiarity with ancient Greek literature and mastery of a Semitic language made Christians such as Ḥunayn perfectly placed to translate from Greek into Arabic. Furthermore, the various Syriac Christian groups, which had previously been caught up in divisive theological controversies, were, after the coming of Islamic rule, no longer under the scrutiny of Constantinople or compelled to adhere to its version of orthodoxy. This meant that communities that had until then been kept apart were now free to work together.