Overview

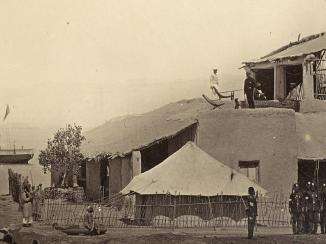

On 2 February 1943 a British plane crash-landed in the Arabian Desert, thirty-five miles east of Sharjah. The plane in question was a Blenheim Bisley (Blenheim Mk V), not a model fondly remembered by servicemen for its reliability. In a memo to RAF Headquarters, the British Political Officer at Sharjah noted that, had it not been for the food and shelter offered by a local Bedouin and his family, the two crash survivors would most likely have perished in the desert.

Several Crashes, Few Fatalities

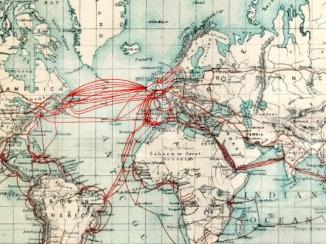

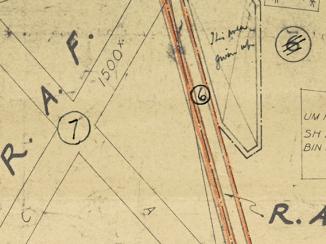

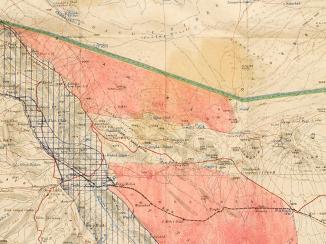

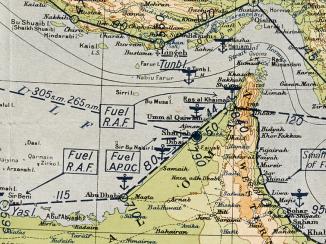

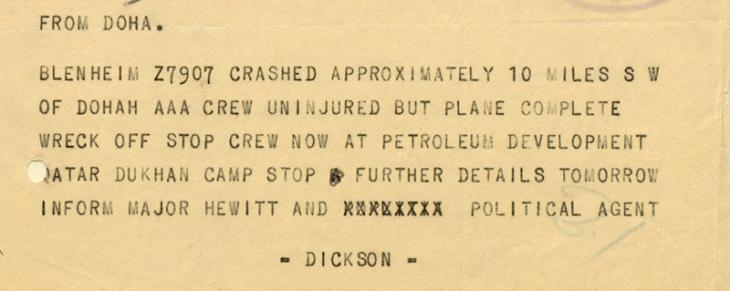

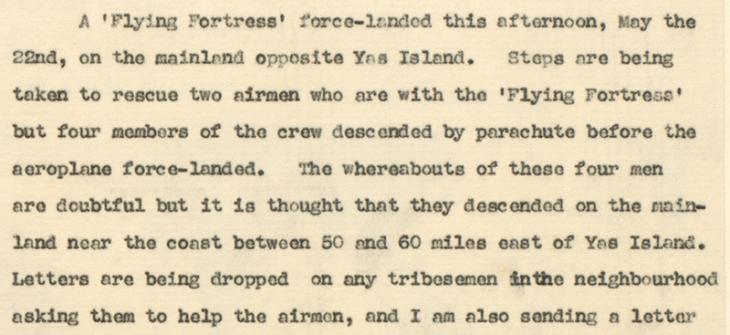

This crash was one of a number that occurred around the shores of the Gulf during the Second World War. They included: a Blenheim Mk IV that crashed outside Doha in December 1941, as a result of its tanks being mistakenly topped up with water instead of fuel at Bahrain; a ‘Boston’ (Douglas A-20 Havoc, company designation DB-7), forced to make an emergency landing on the coast at Tahiri in May 1942; and a ‘Flying Fortress’ (Boeing B-17), which made an emergency landing south of Abu Dhabi in May 1944.

The only fatality recorded in the confidential files of the Political Agency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, headed by an agent. in Bahrain, occurred when a (Vickers) Wellington crashed outside Fujairah, in mid-February 1943. Evidence suggests that the death of the aircraft’s navigator, Sergeant William Donnelly, was Britain’s only wartime fatality in the region now covered by the United Arab Emirates.

Persuading the Population

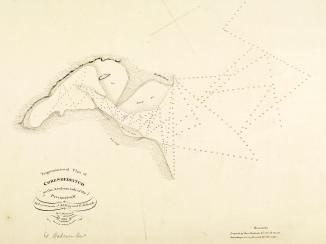

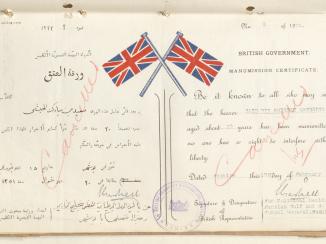

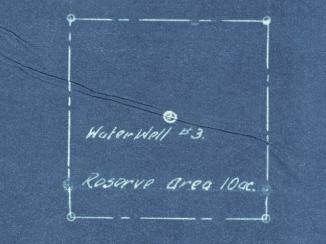

The original treaties signed between the British Government and the Gulf’s Shaikhs for the creation of RAF bases in the Gulf stipulated minimum contact between British servicemen and the native Arab population. But in the case of crashes and emergency landings, the British aircraft crews were reliant on the goodwill of the inhabitants of the areas in which they found themselves. Emergency landings were not uncommon occurrences at the time, a reality acknowledged by the number of emergency landing strips located at strategic points along the Arab coast.

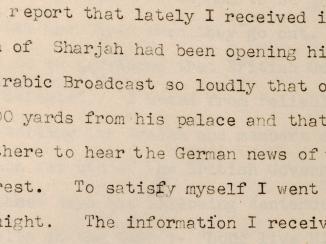

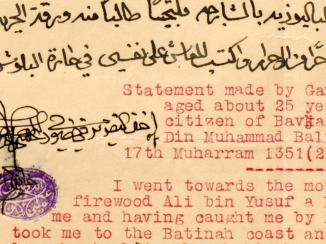

In response to the risk of crash landings, British officials and representatives appear to have worked chiefly through unofficial channels to enlist help from the region’s native inhabitants. In a letter dated 10 March 1943, the Political Officer at Sharjah informed the Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. in Bahrain that he had made much effort to persuade the tribes of the Trucial Coast A name used by Britain from the nineteenth century to 1971 to refer to the present-day United Arab Emirates. and the interior that they should help stranded British servicemen.

In May 1944, when news of the forced landing of an American B-17 Flying Fortress outside Abu Dhabi reached Bahrain, the Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. contacted the Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. Agent in Sharjah, to inform him that letters were being dropped on ‘any tribesmen in the neighbourhood asking them to help the airmen’.

Favours for Favours

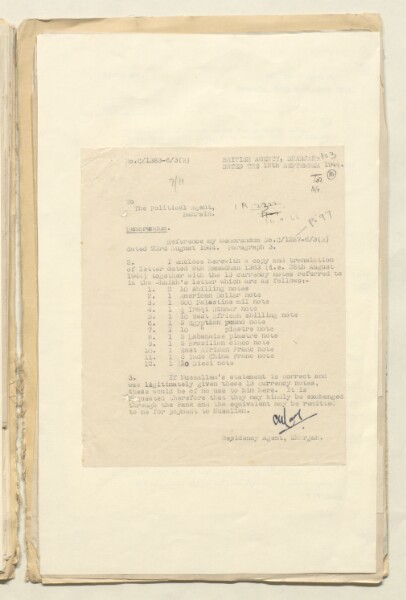

The array of banknotes given to a Bedouin named Musullam by a crewmember of the Flying Fortress, suggests that airmen were well prepared to buy their way out of difficulties, no matter where they ended up. The notes that Musullam was given included British shillings, an American dollar, five-hundred Palestinian mils, a quarter-dinar note from Iraq, ten West African shillings, five Egyptian pounds, five Lebanese piastres, five Brazilian cincos, one East African Franc and five Indo-Chinese francs.

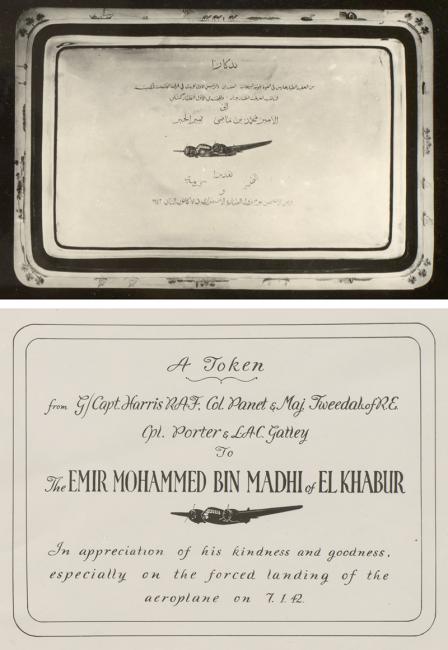

Naturally enough, the degree of appreciation and official gift-giving that took place was largely dictated by a combination of the plane crash’s location and diplomatic protocol. When another British Blenheim crash-landed in Saudi Arabia in January 1942, no time was wasted in passing ‘signals of appreciation’ to Ibn Saud for the help of his people, while the Emir Shaikh Mohammed bin Madhi, in whose district the crash had occurred and whose subjects had directly assisted the Blenheim’s crewmen, was presented with a silver tray for his troubles.

The number of aeroplane crashes and forced landings that occurred in the Gulf during the Second World War demonstrates the fallibility of a modern innovation that was still in its infancy. But in spite of the numerous aerodromes and emergency landing strips that the British had established around the Gulf, aircrews still had to rely on a mix of good luck, goodwill and financial incentive for their safety.