Overview

The British Library’s collection of Arabic manuscripts is internationally recognised as one of the largest and finest in Europe and North America, comprising almost 15,000 works in some 14,000 volumes. It consists of two historic collections: the Arabic manuscripts of the old British Museum Library and those of the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. Library, once part of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office.

Scope of the Collection

This collection is world famous for two reasons; its contents, and the diversity of its subject matter. It contains some of the finest manuscripts of the Holy Quran, as well as autograph and other high-quality copies of major legal, historical, literary and scientific works. The subject matter covers the Quranic sciences and commentaries, hadith, kalam, Islamic jurisprudence, mysticism and philosophy, Arabic grammar and philology, dictionaries, poetry and other literary genres, history, topography and biography, music and other arts, sciences and medicine, texts relating to the Druze and Bahais, Christian and Jewish literature, and other subjects such as magic, archery, falconry and dream interpretation.

Ranging from the early eighth century CE to the nineteenth century, the manuscripts are drawn from both Arab countries and other countries with Arab or Muslim communities including India, China, Indonesia, Malaysia, and West Africa, and they display fascinating variations in style and script.

Foundation Collections

Among the private collections within the British Library’s present holdings are the British Museum Foundation Collections of 1753. These included that of the physician Sir Hans Sloane (1660-1753), which contained approximately 120 Arabic manuscripts, the collection of Claudius James Rich (1786-1821) purchased in 1825 by the British Museum, and that of Richard Johnson (1753-1807) purchased in 1807 by the East India Company. These are typical examples of the way in which items came to the library, either by gift or purchase from those who had worked in India or the Middle East for the British in an official capacity. Rich was Resident at the court of the Pasha An Ottoman title used after the names of certain provincial governors, high-ranking officials and military commanders. in Baghdad where he was well-placed to learn Oriental languages and amass a collection of 390 Arabic manuscripts. Johnson’s career with the East India Company in Lucknow and Hyderabad brought him into close contact with leading artists and writers, through which he acquired a unique collection of manuscripts.

Two other well-placed Government employees were Warren Hastings (1732-1818), and Captain Robert Taylor (1788-1852). Hastings served in the Bengal Civil Service (1750-85), and also was Governor of Bengal (1772), and later Governor-General (1773-85). His collection was formed at considerable expense for his own personal use while in India. Though smaller than Johnson’s, it contained many important works and some finely illustrated Persian manuscripts. Taylor, on the other hand, was an accomplished linguist who served in Bushire, Tehran and Basra before succeeding Rich as Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. at Baghdad. His collection, which included 246 Arabic manuscripts, was sold to the British Museum by his son-in-law T K Lynch in 1860.

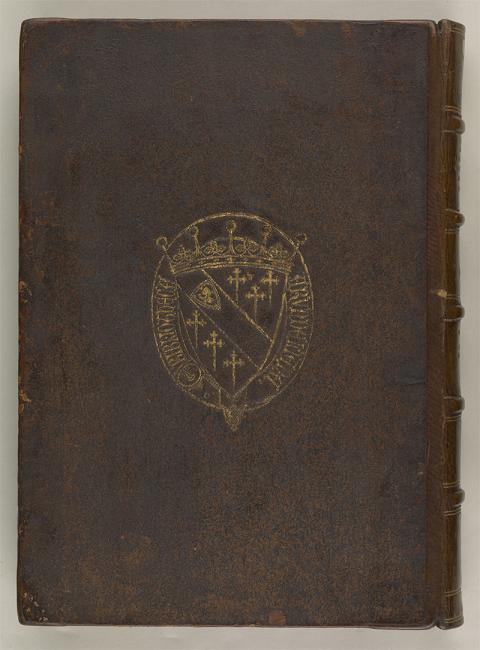

Two other significant additions to the Arabic manuscript collections came from collectors based in the UK. Thomas Howard (1586-1646), Second Earl of Arundel, was an art collector and politician who collected 550 manuscripts now in the British Library of which forty-three are Arabic; they were donated to the Royal Society from which they were purchased by the British Museum in 1831. The manuscript collection of King George III (reg. 1760-1820), which contained seven Arabic manuscripts, was transferred to the British Museum in 1823 by George IV (reg. 1820-1830).

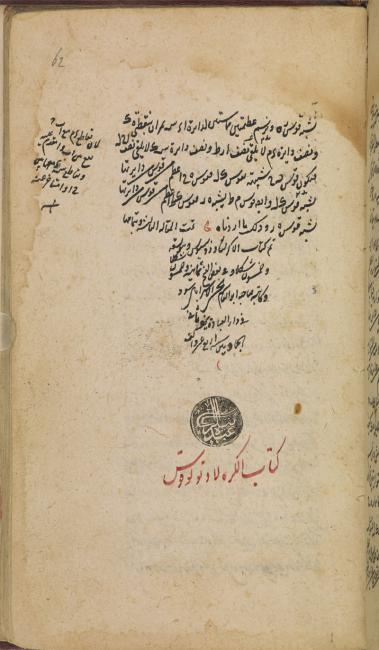

Of final note are those manuscripts representing what remained in 1858 of the Royal Library of the Mughal emperors. The traveller Mandelslo described their contents in 1638 as ‘Four and twenty thousand Manuscripts, so richly bound, that they were valued at six Millions four hundred and sixty three thousand, seven hundred thirty one Roplas’. Between 1638 and 1858 several items from the Moghul library were gifted to Heads of State and other high-ranking individuals, and as early as 1810 many were in the hands of private collectors. The Government of India purchased the manuscripts of the Royal Library in 1859 for the sum of 14,955 rupees Indian silver coin also widely used in the Persian Gulf. . After some 1,120 volumes had been sold, the remainder was transferred to the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. in 1876.

The Formation of the Collections

The way the collection has been formed over the past few centuries is extraordinary. Its early development, primarily due to the growth of British trading and political interests both in the Middle East and further afield in the Islamic world, notably the Indian subcontinent, reflects a great upsurge of European interest in Oriental studies during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Its size and breadth reflects the process by which a number of private collections – formed by administrators, missionaries, scholars and travellers – have been augmented by more recent acquisitions by British Museum and British Library curators to form a great public collection and remarkable international resource.

Further information about the Arabic manuscripts and their Catalogues is on the British Library website.