Overview

Early methods of creating and storing natural ice

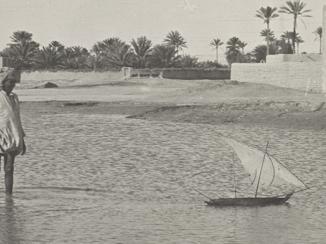

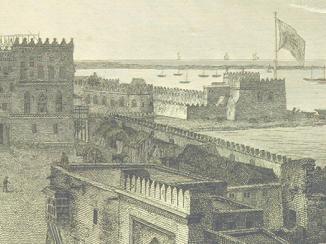

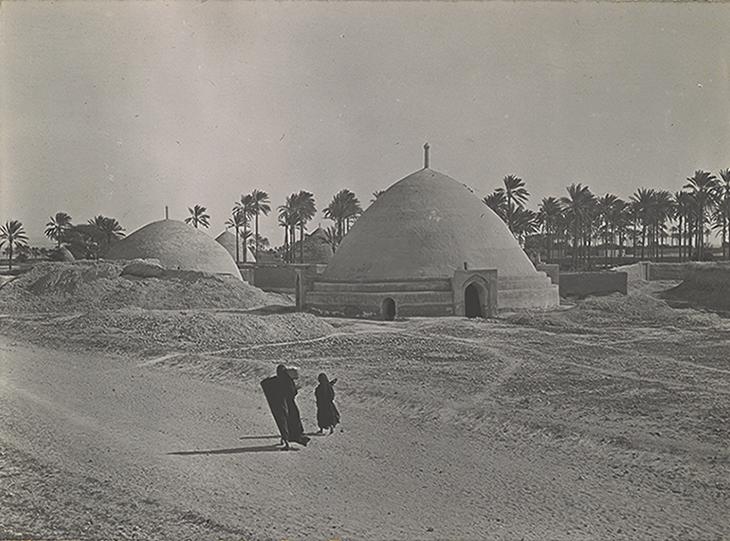

As early as the first millennium BCE, people were gathering ice during the winter and storing it in pits for use later in the year. This technique led to the development of yakhchāls (ice houses) in Persia [Iran], which kept ice available all the way into the summer. Either water was brought into the ice houses via covered channels called qanats, or it was diverted into shallow, sheltered trenches and collected once it had frozen. The British adapted this method for use near their stations on the north Indian plains. Alternatively, ice was transported from colder areas where it was present all year round, such as high mountainous regions or glaciers. These were still being used as a source of ice into the twentieth century.

Seventeenth-century European travellers such as Jan Janszoon Struys were impressed by the wide availability of ice in Persia, and noted that all social classes were able to enjoy it throughout the year. Although ice houses existed in England by this time, they were still relatively rare and iced products remained the preserve of the upper classes. Even in the early nineteenth century, James Edward Alexander exclaimed at the luxury of having ice ‘throughout the most disagreeable months of the year’ in such a hot climate as Persia (IOL.1947.b.134, p. 142).

In the nineteenth century, other sources of natural ice became available. The American entrepreneur, Frederic Tudor, who became known as the ‘Ice King’, made a fortune importing ice from Boston to India, with his first shipment reaching Kolkata in 1833. This was far cheaper than bringing snow from the mountains, and the ice was clearer and cleaner than any collected from ice trenches. Soon, imported ice was common in the Presidency The name given to each of the three divisions of the territory of the East India Company, and later the British Raj, on the Indian subcontinent. seaports of Kolkata, Mumbai, and Chennai.

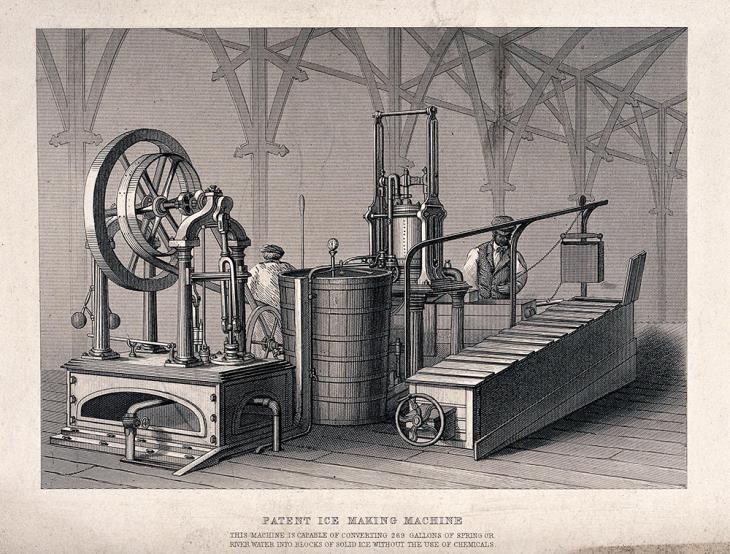

The coming of artificial ice

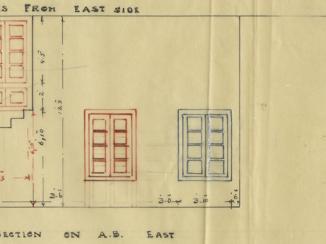

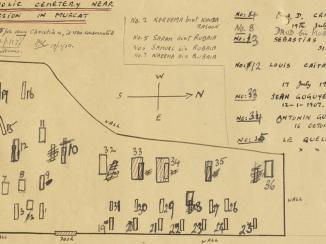

Traditional methods of creating and storing ice continued alongside new artificial methods. Steam-powered water condensers, which produced pure water from sea water, were installed in Aden in the mid-nineteenth century by the British Government. Combined with ice machines, they allowed pure ice to be produced. However, other sources of water were also used, and artificially-produced ice was not always clean. In Bahrain in the 1930s, the British Agency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, headed by an agent. staff complained that the ice produced by the municipal plant was so dirty that it could not be used directly in drinking water, and instead bottles of water had to be cooled by using an ice chest, a much less efficient method.

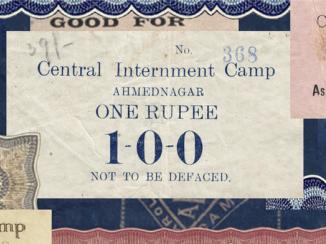

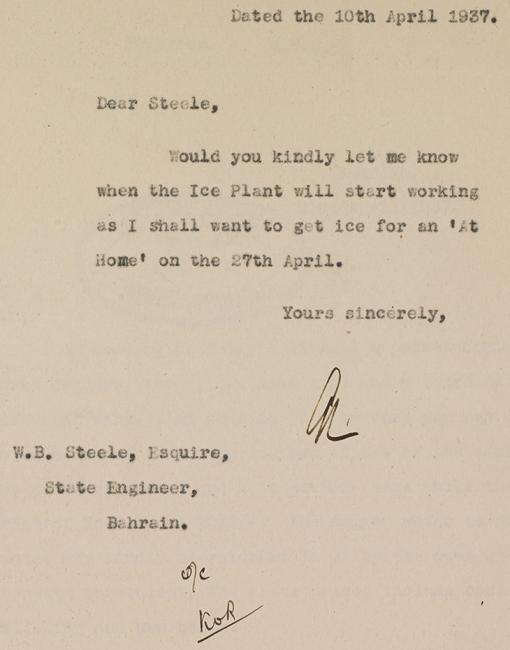

Only the very wealthiest could afford their own ice machines. In the early twentieth century, most people had to buy ice from ice shops, which were supplied by factories. Due to the high demand, these factories could face significant pressure and become sources of tension. In Baghdad in 1910, an Indian subject, Abdul ʿAli Adamji, who owned two ice factories with his brothers, had a dispute with the Vali of Baghdad who forced them to sell their ice at a loss, and attempted to shut down their factories. This would have allowed the municipal plant to monopolise ice production. Bahrain was also the site of a legal clash in the 1930s. The Manama Municipality claimed they had a monopoly on supplying ice, since Shaikh Hamad bin ʿIsa Al Khalifa, the ruler of Bahrain, had sold them his share of an ice plant set up jointly with Yusuf Lutf ʿAli Khunji. Yusuf contested this claim, as he still owned half the plant. Once the Municipality gave up their monopoly in 1937, the increasingly-demanding population faced ice shortages. By the 1940s, however, there was strong competition among ice manufactures, with accusations that ice was being sold on the black market, above the controlled price set by the Manama Municipality.

An essential product

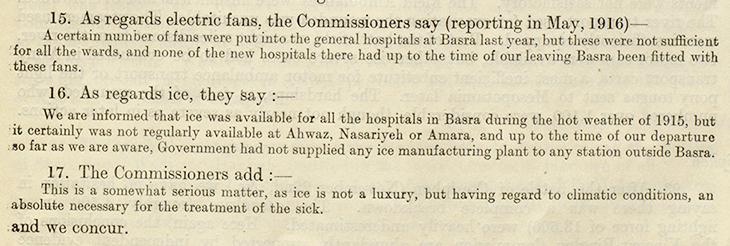

The importance of a proper ice supply was brought home during the First World War. A commission set up to investigate shortcomings in British military operations in Mesopotamia described it as ‘a somewhat serious matter’ that ice was in short supply. Ice was deemed essential, not just for the comfort of British troops, but also to treat potentially fatal conditions such as heatstroke.

This had also been its function on board steamers, where high temperatures could cause stokers to collapse, and ice was needed to revive them. In addition, the magazine and gun turrets on warships had the potential to overheat, so ice was used to cool these parts. However, even after ice-making machines had been developed, steam ships did not carry them on board, as the early machines relied on potentially explosive chemicals. Instead, they took ice on board at ports such as Aden.

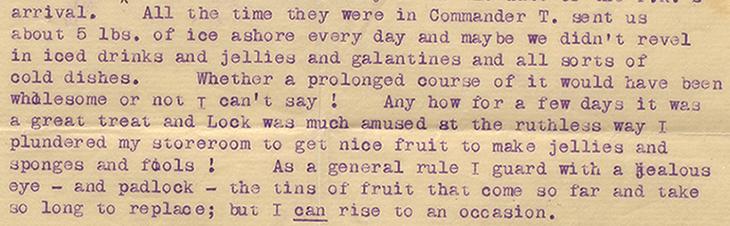

When ships started to carry their own ice machines for essential reasons in the 1880s, they supplied ports with ice for luxury purposes. Emily Lorimer, a linguist living in Bahrain with her husband, the Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. , describes this in a letter to her parents. She tells them that since the arrival of HMS Sphinx, the ship has been sending them 5lbs of ice a day, which she has used to create jellies, galantines, and other iced dishes.

By the 1930s, however, ice production was considered a necessity. In 1936, the Perim Coal Company, which ran all the services on Perim, including the ice plant, was considering leaving the island. This generated much discussion about which services would now have to be run by British officials, and ice supply was deemed to be as important as the production of electricity. The plant had been a net earner for the Company, because it had been able to supply passing ships with ice, but since ships would no longer be calling at Perim after the Company left, the plant would not pay for its own upkeep. British officials on the island nevertheless decided it was an essential expense.

Ice brought change to the fishing industry too, making it possible to keep fish for longer, and transport it further without drying it. The Second World War disrupted supplies of tinned meat, and to compensate for this, British officials tried to implement a fresh fish scheme to keep the people of Abadan supplied with protein. However, limited ice supply in 1944 halted a proposed expansion of this scheme, since it relied on the transport of fish from the mouth of the Shatt al-Arab. Conversely, in 1943, the Manama Majlis made it illegal in Bahrain to store fish on ice for public sale in order to prevent hoarding and food shortages.

Luxury

Despite the many practical uses of ice and its ubiquity and cheapness, abundant ice remained a sign of luxury. Emily Lorimer’s most flamboyant social events would not have been complete without ice, and even when it was not otherwise available, she would buy expensive snow from the mountains to complete her iced dishes. Any impressive gathering demanded iced water, if no other refinement, while elaborate flavoured ice shapes and sherbets formed centrepieces to picnics and dinners in Iran. Highly valued and viewed as a status symbol (especially by Europeans), ice has nevertheless been readily available across the Gulf region throughout much of history, even if not in quantities that could match demand.