Overview

Part 2 is forthcoming.

Murky Beginnings

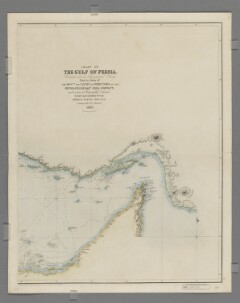

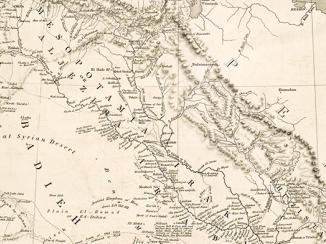

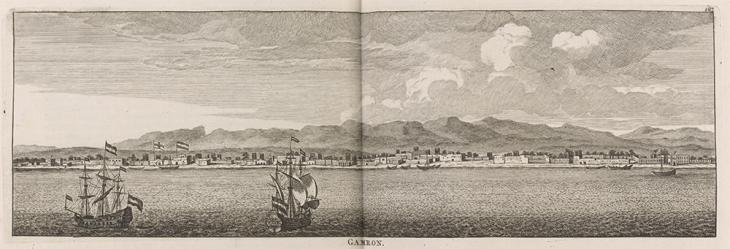

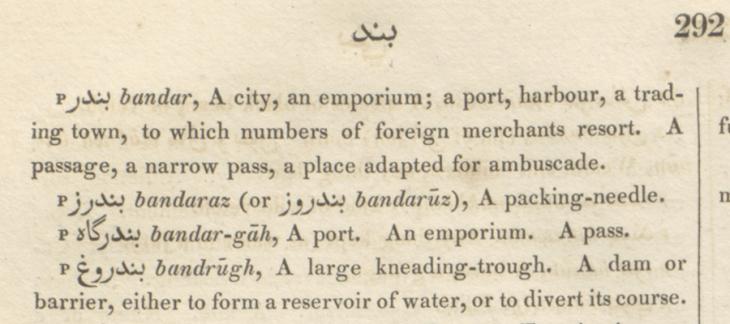

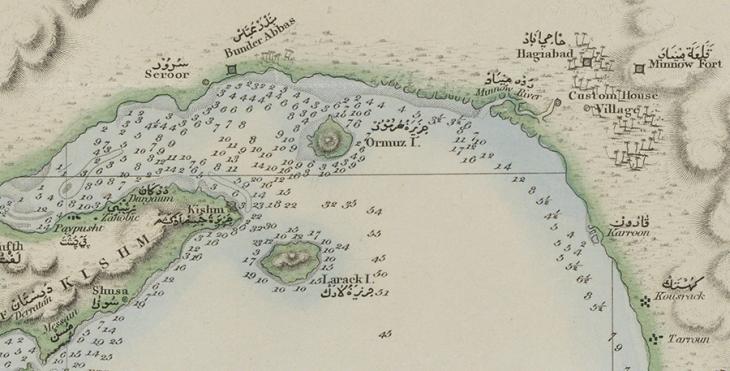

Under a lease agreement originally signed in 1794, the Sultan of Muscat and Oman administered the port of Bandar Abbas, on the southern coast of Persia [Iran], for seventy-five years. Throughout the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, Bandar Abbas had been Persia’s premier port. From the 1740s, however, that distinction began to switch to Bushehr and Bandar Abbas went into a steep decline. Furthermore, the agreement was preceded by a long period of civil war in Persia and the overthrow of the Shah, Lutf ‘Ali Khan Zand. During this time, the area had experienced various invasions and occupations, including by the Sultan himself, Sultan bin Ahmad Al Bu Sa‘id (often referred to in the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. Records as the ‘Imam of Muscat’). For the new Shah, Agha Muhammad Khan Qajar, handing over the contested area to a powerful outside force was probably a strategic move. The benefits to the Sultan were likewise strategic, but also commercial.

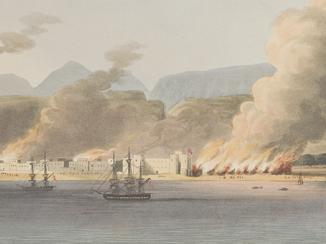

The first challenge to the Omani lease came after Sultan bin Ahmad’s death in 1804. Taking advantage of a dynastic power struggle in Muscat, Mulla Husayn Al Mu‘in, the ruler of Qeshm, seized Bandar Abbas. Once the situation in Muscat had been resolved, the new regent, Badr bin Sayf Al Bu Sa‘id, set sail to reclaim the port. In a letter dated 1805, David Seton, the British Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. at Muscat, recounts Badr bin Sayf’s arrival on the evening of 5 June, saying that by the next morning ‘he had driven the Garrisons within the Walls’ (IOR/F/4/190/4155, f. 47r). A siege of several months followed before Mulla Husayn was forced to surrender, thanks to cooperation ‘afforded to Syed Bader by the Honorable [sic] Company’s Marine’ (IOR/F/4/190/4155, f. 10r). However, this British assistance was not altruistic. Badr bin Sayf subsequently allowed the East India Company to establish a Factory An East India Company trading post. in the town, their first official presence there since 1762. This renewed British interest perhaps shows that Bandar Abbas’ status had already revived under a decade of Omani control, with Seton commenting that ‘there is no place in the Gulph [sic] equal to it for convenience in respect to trade’ (IOR/F/4/190/4155, f. 42v).

Contested Terms

The next threat to Omani control came in 1820, and was again linked to Qeshm. In January, the Company imposed the General Treaty with the Arab Tribes of the Persian Gulf on the rulers of five emirates in today’s UAE. In order to ensure the terms of the treaty were kept, the Company asked the Sultan, Sa‘id bin Sultan Al Bu Sa‘id, for permission to place troops on Qeshm. He readily assented, but the Government of Persia opposed the move, denying that the Sultan had any right to grant such permission regarding Persian territory. In December, they even made the unfounded claim that ‘Muscat is a dependency of Persia’, but also made clear that they viewed the Sultan as governing ‘on [the] part of Persia’ in the same way as any regional Governor (IOR/L/PS/5/369, f. 10r). Despite this opposition, and reports that Husayn ʿAli Mirza Farmanfarma, the Prince-Governor A Prince of the Royal line who also acted as Governor of a large Iranian province during the Qājār period (1794-1925). of Fars, was raising troops to march on Bandar Abbas, Britain retained a military presence on Qeshm for the remainder of the Omani lease.

The events of 1820 called into question, not for the last time, the exact terms of the 1794 agreement. Though the Persian Government may have wished him to behave as a Governor under their suzerainty, the Sultan treated the agreement as giving him complete control over Bandar Abbas, as well as the surrounding coastline and neighbouring islands including Qeshm and Hormuz. For their part, British officers in the Gulf did not seem to have definite evidence that would support or disprove either view. Although the British spy John Lewis Reinaud had reported in 1797 that Sultan bin Ahmad had ‘obtained’ Bandar Abbas to be ‘under his Government’, the British Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. at Basra, Samuel Manesty, nevertheless wrote the same year that Sultan bin Ahmed had offered to become the Shah’s ‘Vassal, and tributary’ (IOR/G/29/23, f. 591v). Overall, the Company tended to support the Sultan’s view, but this is likely to have been a strategic rather than evidence-based position.

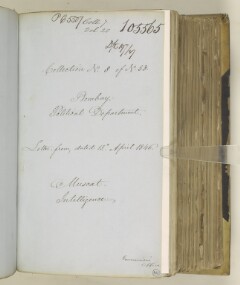

Unpaid Rents

Tensions remained, but did not significantly flare up again until 1844, when the Governor of Kerman threatened to attack Bandar Abbas over failure to pay the rent. Whatever level of independence the Omani administration may have been entitled to, the one fact that seems undisputed is that the Sultan was liable to pay rent to the Persian Government of around 4000 tomans 10,000 Persian dinars, or a gold coin of that value. a year. It is also clear that in several years this rent was not paid. In 1821, the Chief Secretary to the Government of Bombay From c. 1668-1858, the East India Company’s administration in the city of Bombay [Mumbai] and western India. From 1858-1947, a subdivision of the British Raj. It was responsible for British relations with the Gulf and Red Sea regions. , Francis Warden, wrote of the rent that ‘the [Sultan] has refused to pay and Persia been unable to exact, since the death of Shah Abbas’ (IOR/L/PS/5/369, f. 35v). However, since the eponymous Shah Abbas had died over 160 years before the 1794 agreement, this statement betrays a certain ignorance. Considering that the Persian Government believed the Sultan to be acting beyond his rights and without providing the agreed revenue, the question arises of why they did not simply cancel the lease. The answer comes in a letter of 1844 from the British Minister at Tehran, Justin Sheil, to the Persian Prime Minister, Hajji Mirza Aqasi, warning ‘of the inexpediency of provoking a quarrel with the [Sultan], who from his Naval Superiority was able to molest the Coasts of Persia and interrupt her maritime trade’ (IOR/L/PS/5/432, f. 474r). The Sultan of Muscat held enough naval power to act however he liked in relation to Bandar Abbas.

Despite the warning, Persian threats and even attempts to take back Bandar Abbas became a regular occurrence. In 1846, the Prince-Governor A Prince of the Royal line who also acted as Governor of a large Iranian province during the Qājār period (1794-1925). of Fars, Husayn Khan Ajudan Bashi, marched an army towards Bandar Abbas and sent a messenger to the Sultan’s Governor, Sayf bin Nabhan al-Ma‘wali, demanding that he give up the town or pay 30,000 tomans 10,000 Persian dinars, or a gold coin of that value. . The demand was rejected and the Persian force repulsed. The Sultan announced that, if such actions continued, ‘he would retaliate by destroying Bushire [Bushehr]’ (IOR/L/PS/5/446, f. 282v). The Persian Government condemned the Prince-Governor’s expedition and claimed to have had no prior knowledge of it, with Samuel Hennell, the Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. , predicting that ‘under the expressed displeasures of the Persian Court, it is not likely to be repeated’ (IOR/L/PS/5/446, f. 280r).

Competing Threats

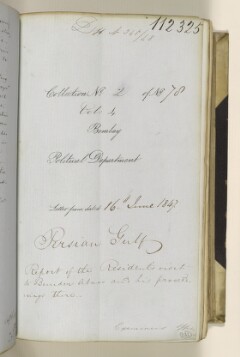

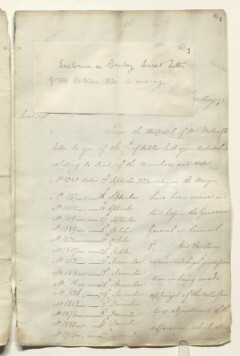

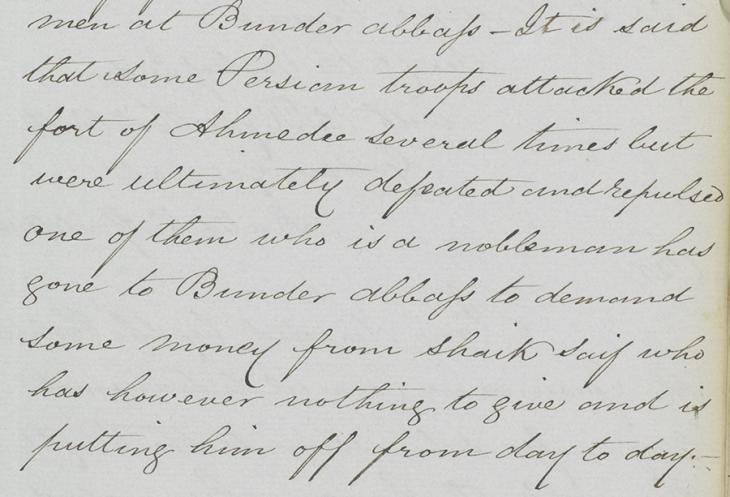

By the 1840s, the balance of power had shifted. Sa‘id bin Sultan, had transferred his government from Muscat to Zanzibar, about 2,500 miles away from Bandar Abbas, leaving Sayf bin Nabhan with considerably more autonomy than previous Omani Governors. British sympathies with the Omani cause were also fading, largely due to their repeated threats to destroy or blockade Persian ports, which would have been disastrous to British trade. In 1847, Sayf bin Nabhan continued reporting threats and demands for money from Husayn Khan, but the British Consul at Zanzibar, Atkins Hamerton, dismissed these as exaggerations. The Sultan responded that he ‘would retaliate tenfold by the destruction of every Persian Port lying between Bunder Abass, and Bushire’, claiming falsely that ‘he had already received the sanction, and approval of the British Government’ (IOR/F/4/2238/112325, f. 239v). British officials remained unconvinced, with Sheil claiming that the Governor of Fars had neither the power nor the means to take hostile action, and characterising Sayf bin Nabhan’s motivation as ‘frivolous and insufficient’ (IOR/L/PS/5/452, f. 78r).

In October, Sayf bin Nabhan wrote that Fazl ‘Ali Khan Qarabaghi, the Governor of Kerman, and his army were approaching ‘my Districts, and will certainly do them some injuries’ (IOR/L/PS/5/453, f. 453r). Hajji Mirza Aqasi responded that the Governor was merely marching to reinforce the frontier with Baluchistan. However, in January 1848 Hennell reported that Fazl ‘Ali Khan had ‘committed great excesses’ in the neighbourhood of Bandar Abbas, adding that he doubted such an attack could have happened ‘without the knowledge or connivance of the [Persian] Prime Minister’ (IOR/L/PS/5/453, f. 330r-v). The Persian force was again repulsed, and Fazl ‘Ali Khan proposed to withdraw if the Omanis would agree to pay 2,500 tomans 10,000 Persian dinars, or a gold coin of that value. . Hennell reported that Sayf bin Nabhan had ‘ostensibly agreed to pay […] and the Kerman Army has consequently vacated’, but added with a little more foresight than in 1846 that ‘it is doubtful whether it will be paid’ (IOR/L/PS/5/453, f. 333r-v).