Overview

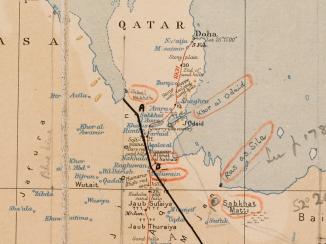

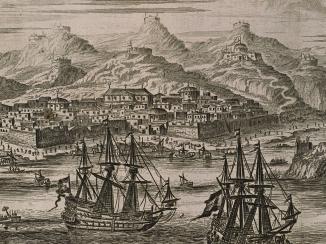

In the late 1940s, Qatar’s nascent oil industry was beginning to flourish. With the growing need for both infrastructure and bureaucracy to support this new industry, events were developing quickly in the eyes of British officials in the Gulf. Until then British relations with the Ruler of Qatar had been handled by the Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. in Bahrain, who in turn reported to the Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. based in Bushehr (and later Bahrain). However, after the end of the Second World War, considerable discussion ensued between the Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. and the Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. as to the best way of strengthening Britain’s presence in Doha.

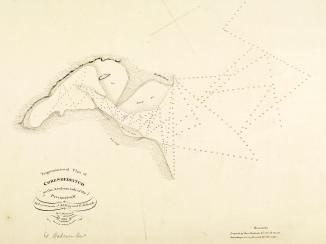

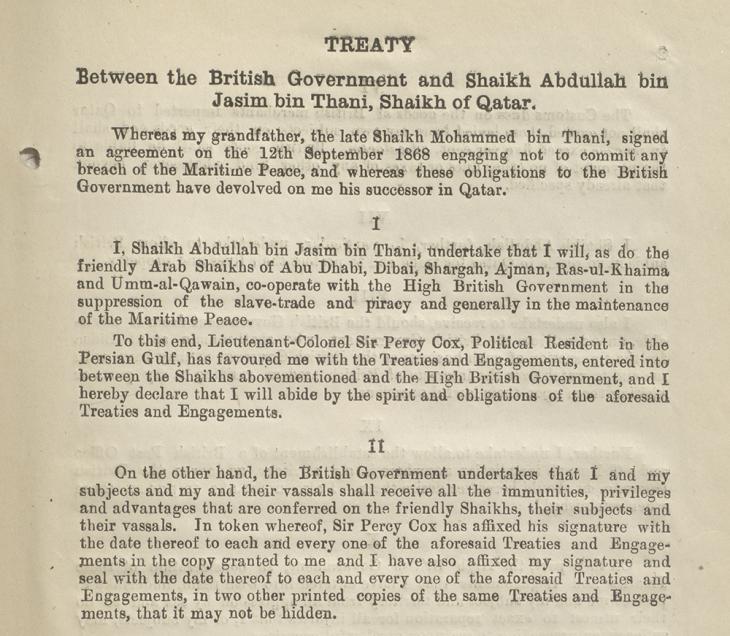

Origins of British involvement with Qatar

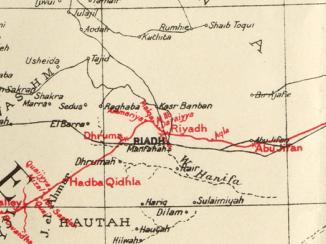

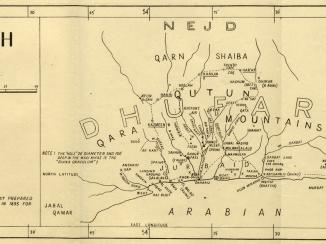

In 1868, the Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. in the Gulf, Lewis Pelly, and Shaikh Muhammed bin Thani had signed a treaty, establishing formal political relations between Qatar and Britain. While this moment can be seen as a crucial step towards Qatar’s emergence as an independent state, nevertheless until the First World War Britain largely saw Qatar as an Ottoman area of interest. The British accordingly trod carefully in their dealings with the Al Thani rulers. However, following the exit of the Ottomans from the Gulf, the Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. , Sir Percy Cox, agreed a second treaty with Shaikh Abdullah bin Jasim Al Thani in 1916. This was further augmented in the mid-1930s, and a year later Qatar awarded an oil concession to a British company, Petroleum Development (Qatar) Limited.

Perhaps mindful of the implications of accepting Britain’s smothering imperial embrace, Shaikh Abdullah had managed to ensure that articles seven, eight, and nine of the 1916 Treaty would remain in abeyance. These included the article permitting Britain to appoint a Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. in Qatar. Cox had confirmed the suspension of these articles in a side letter to Shaikh Abdullah, dated 3 November 1916, which accompanied the Treaty. At that time, the British had no pressing interests in Qatar that could not be handled from Bahrain.

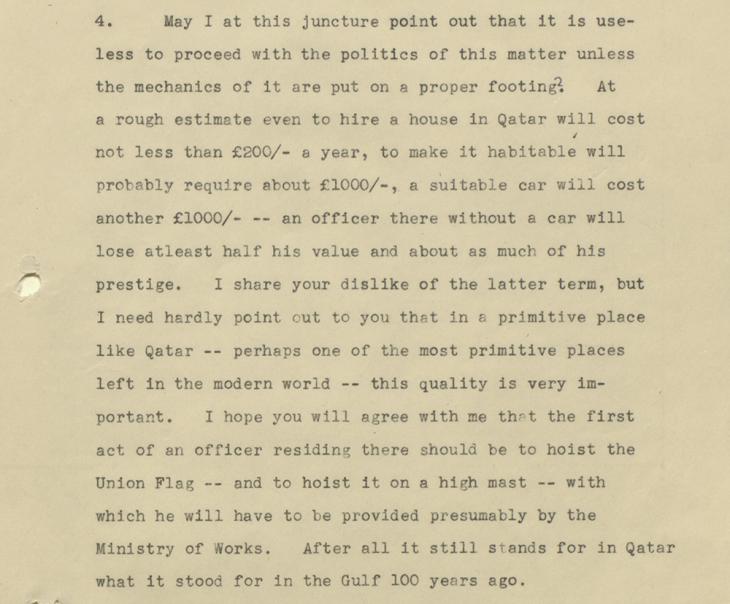

The Politics of Prestige and Petroleum

Oil was discovered in Qatar in 1939, but production was soon suspended due to the Second World War. When production resumed, the Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. in Bahrain, Cornelius James Pelly, while extremely condescending about the conditions in Qatar, was nevertheless firmly of the view that it was now ‘highly important that we make a beginning really to get into Qatar’ (IOR/R/15/2/2000, f. 7r). Pelly initially argued against the appointment of an Assistant Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. for Qatar, suggesting instead the establishment of a Rest House in Doha (similar to that in Gwadar). This would allow the Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. in Bahrain to keep abreast of matters through regular monthly visits. Writing to Sir Rupert Hay in his capacity as Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. , Pelly pointedly adds that the house would need to be furnished with a car, since ‘an officer there without a car will lose at least half of his value and about as much of his prestige.’

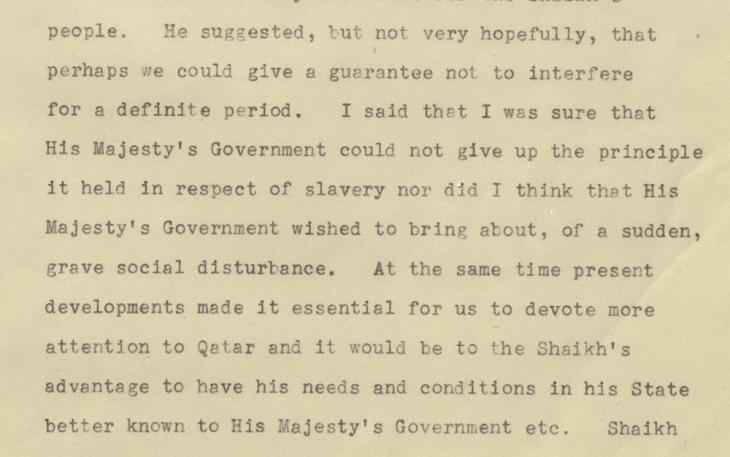

Addressing Shaikh Abdullah’s Concerns

Shaikh Abdullah, however, seems to have been apprehensive. Pelly reports that Shaikh Abdullah was worried about the impact of a Rest House on the assurances given to him by the British in 1916, especially concerning the guarantee of ‘non-interference in the matter of existing slaves’ (IOR/R/15/2/2000, f. 9r). According to Pelly, Shaikh Abdullah had concerns that ‘if the Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. was going to stay 4 or 5 days at a time in Doha […] every slave in the place would be at his door clamouring to leave his master; and this would be very difficult for the Shaikh’s people’ (f. 6r). Pelly further recounts that the Shaikh declared ‘without prompting, that he himself was fiercely opposed to enslavement (which incidentally I believe to be true as regards the Shaikh personally)’ (f. 9r).

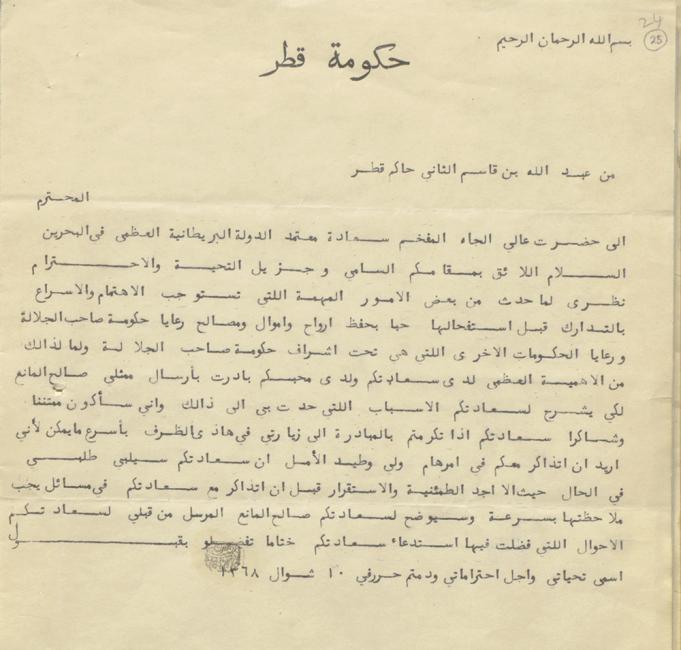

Later that year, Shaikh Abdullah wrote to the Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. in Bahrain (Herbert George Jakins had by now replaced Pelly) to request that he visit him in Qatar with a view to discussing all these matters in person.

Following this meeting, Jakins advanced a draft agreement recognising that Shaikh Abdullah had ‘not conceded […] the right of the manumission of slaves, and any Agent appointed to Qatar will not, therefore, attempt to exercise such a right except in cases where definite cruelty by a master towards a slave seeking manumission has been proved’ (IOR/R/15/2/2000, f. 18r). By contrast, however, Shaikh Abdullah’s full cooperation was expected in the event of any new abductions or kidnappings concerning Qatari territory.

The New Political Officer, Qatar

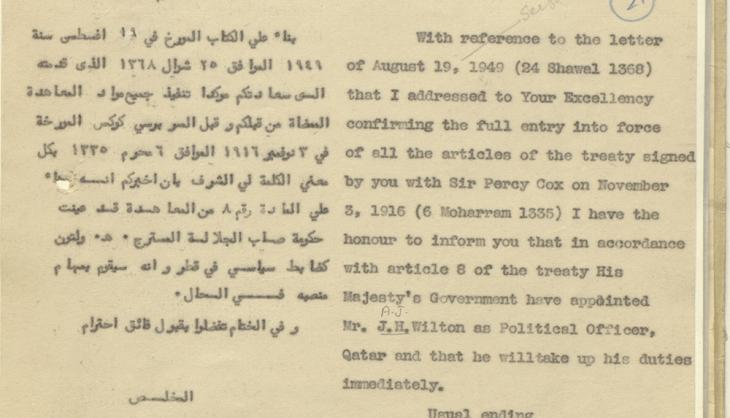

Having allayed Shaikh Abdullah’s concerns, the British informed him on 19 August 1949 that all the articles of the 1916 Treaty had come into force, and that Arthur John Wilton had been appointed to work as the Political Officer in Qatar, with immediate effect.

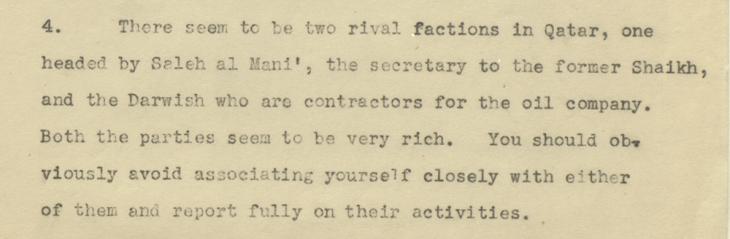

Wilton was to report to the Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. in Bahrain, who briefed him on Qatari affairs prior to his taking up the new post. The briefing includes the observation that there were two rival factions in Qatar, and advises Wilton that he ‘should obviously avoid associating yourself closely with either of them and report fully on their activities.’

While matters were somewhat complicated by the abdication of Shaikh Abdullah, Wilton nevertheless arrived on 23 August 1949 to take up his post in Qatar. He was advised on the order of precedence of his calls: he should visit the new ruler, Shaikh Ali, ‘on the first day and postpone calling on Shaikh Abdullah and others until the second day’ (IOR/R/15/2/1048, f. 2r). Due to Britain’s lack of interest and Shaikh Abdullah’s subtle negotiating skills, key parts of the 1916 Qatar Treaty had remained unimplemented for over thirty years. Now at last with a “man on the ground”, the British Government could better assess and manage issues of imperial involvement on the Qatar Peninsula, which were becoming increasingly significant with every new oil well sunk. Britain finally had a foot in the door at Doha.