Overview

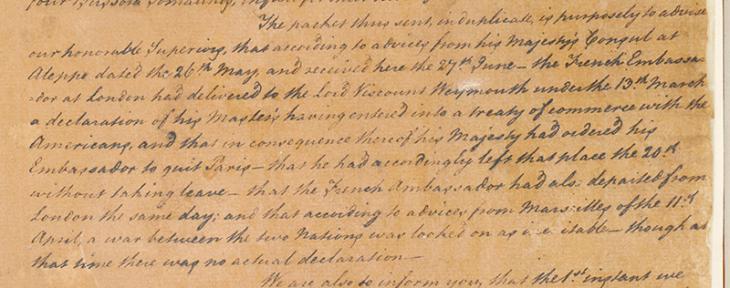

On 26 June 1778, reports reached Basra from Aleppo that the ambassadors of France and Britain had been instructed to leave their posts and that an outbreak of war was seen as inevitable.

Although the late 1780s were a time of intense Anglo-French competition, it was the signing of a Treaty of Alliance between France and the United States of America in February 1778 that triggered initial hostilities between Britain and France.

After Britain declared war, France persuaded its ally Spain to enter into hostilities with Britain. This Anglo-French imperial competition was played out globally: on the American continent and in India. The Gulf was no exception. As a result the English East India Company (EIC) found itself on one side of a global stand-off and, as such, began to gain intelligence on the movement of French ships, along the strategically important waterway of the Gulf.

Safeguarding Strategic Communications

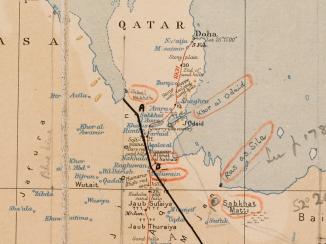

Ascertaining the location of French ships was of principal importance. In August 1781, William Digges Latouche, the Agent at Basra, wrote to Edward Galley, the Resident in Bushire. He did not wish to allow ships to depart from Basra until the French ships had made their way out of the Gulf or English ships had entered the Gulf from Bombay in order to protect the movement of important people and packets.

Since receipt thereof [letters] I have no certain accounts of the French Cruizers – some reports say that they were at Carrack a few days ago, and were endeavouring to get a pilot for Bussora, others that they are returned to the Southward […] I am obliged to you for the early Intelligence you have given me regarding them – the Mercury is still here, and will not sail with Mr Sulivan [sic] who arrived the 5th instant from Constantinople until I am certain that the French ships have left the Gulph, or that the expected ships from Bombay have entered it.

Digges Latouche had qualms about allowing the Mercury to sail with an important person such as John Sullivan aboard when the French cruisers were still in the Gulf and British support was yet to arrive from Bengal. Sullivan was on his way to his new appointment as resident at the court of Tanjore, India where he was to be responsible for the Madras Presidency’s southern provinces. His capture would surely have been a feather in the cap for the French. Meanwhile the British were keen to intercept any French messengers they could, to gain intelligence on enemy plans and movements and the French similarly intervened against the British if opportunity allowed.

Keeping Watch on the French

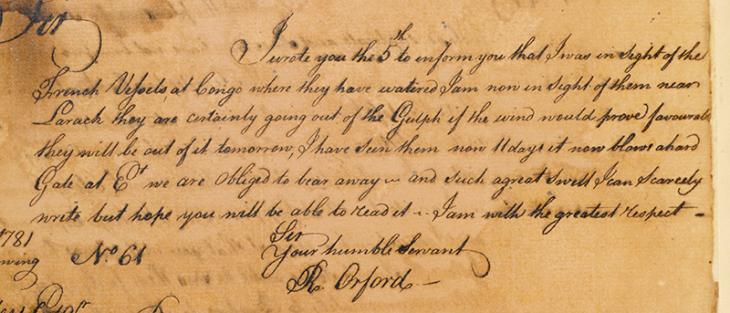

Accordingly, in August 1781, an EIC spy, Roger Orford, kept watch on French ships making their way down the Gulf. He informed Digges Latouche:

Sir, I wrote you the 5th to inform you that I was in sight of the French Vessels at Congoon [Kangan] where they have watered I am now in sight of them near Carach [Carrack] they are certainly going out of the Gulph if the wind would prove favourable they will be out of it tomorrow, I have seen them now 11 days…

Orford had ears and eyes on the ship:

I have two excellent Spies in the boat who go to Congo [Congoon or Kangan] whenever I chuse and bring me every intelligence, they are now gone to that place – the Ship has just fired a Gun and loozed her top Sails. I believe they are now weighing.

Orford’s reports were sometimes written under difficult conditions: ‘ it now blows hard Gale at East we are obliged to bear away – and such a great swell I can scarcely write but hope you will be able to read it.’ We can only speculate how Orford received and sent communication to his spies on board and whether he could rely on them, but clearly Digges Latouche valued this information source.

Correspondence between the two men illustrates the practical difficulties of maintaining intelligence on the movement of rivals as well as the necessity of securing this strategic communication route and the safe passage of important people and packets. Furthermore, it reflects how the Gulf in the 1780s was part and parcel of global competition between these two great European powers.