Overview

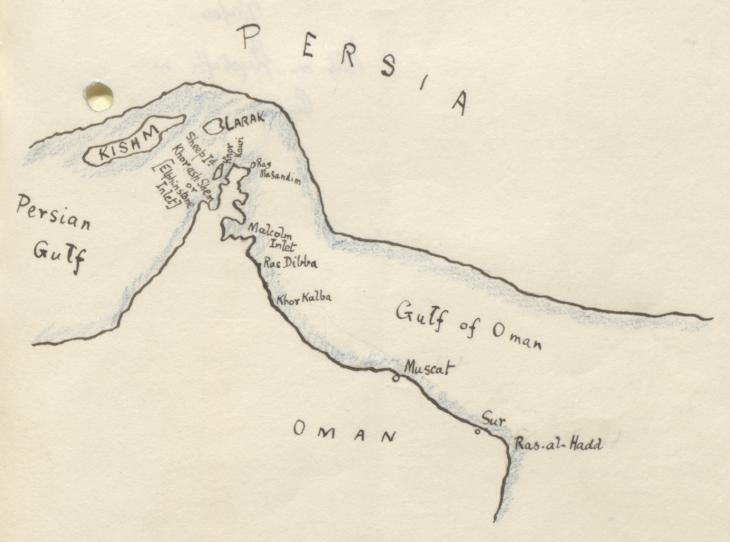

Following the expulsion of the Portuguese from the Gulf and the coast of Oman by the Ya‘rubid Dynasty in the seventeenth century, the rulers of Muscat consistently maintained a claim over Musandam. First the Ya‘rubi held sway, then the Al Bu Sa‘id Dynasty. The latter went on to become the leading power in the western Indian Ocean, controlling lands on the Persian coast of the Gulf and as far away as Gwadur and Zanzibar. However, this dominance was not without the involvement of the British Empire.

Britain, Muscat, and Musandam in the Nineteenth Century

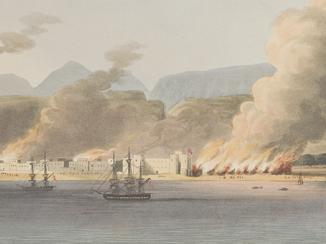

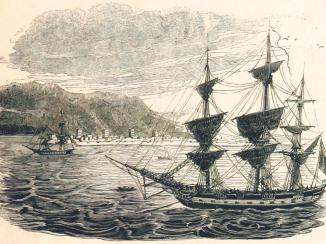

With the razing of Ra’s al-Khaymah in the punitive expedition against the Qawasim in 1819, Britain completed its shift from a trading presence to being a major imperial power in the Gulf. Britain saw the region as one of the outer frontiers of the British Raj, the centrepiece of a global empire whose lines of supply were vital to protect. It was in this context that the coastline of the Gulf became an informal protectorate. While still officially independent, the Sultans of Muscat became increasingly reliant on British power to sustain their position, particularly after the separation of Zanzibar from the Sultanate of Muscat in 1861. The changing relationship was reflected in various special treaties giving Britain exclusive rights: for example, the 1891 Treaty (in English; in Arabic) specified that the Sultan would never cede or mortgage any part of his territory to any power other than Britain. It was partly for this reason that Britain helped the Sultan of Muscat to maintain his rule in various parts of his domains, including Musandam.

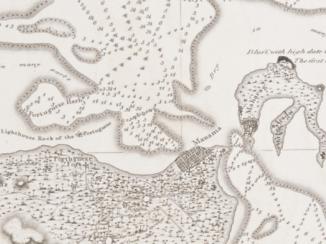

The Musandam Peninsula proved to be of strategic importance to Britain, not least for communications. On 17 November 1864, Lewis Pelly, the British Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. , signed an agreement with Sayyid Thuwayni bin Sa‘id Al Bu Sa‘id, Sultan of Muscat, which allowed the British to construct a telegraph station on Telegraph Island (also known as Jazīrat Maqlab). Due to its isolated location, being stationed on Telegraph Island was considered a hardship; it is possible that the winding topography of its coastal inlet gave rise to the phrase ‘going round the bend’. The station was soon abandoned in 1868, when a new cable was laid along the Persian coastline.

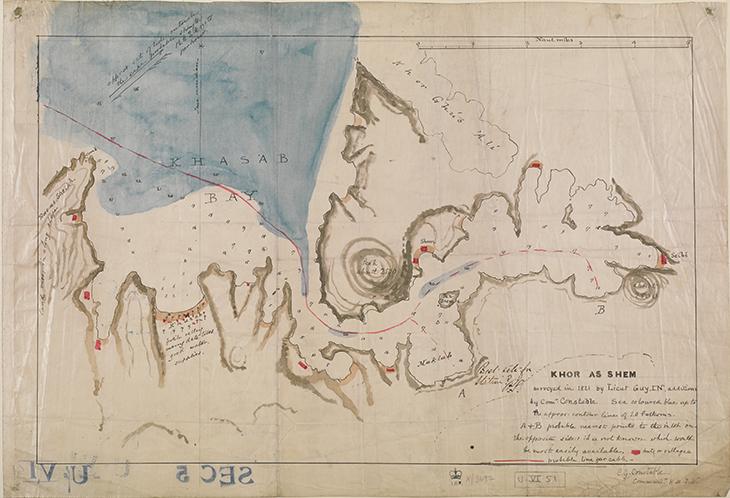

Among other key locations in Musandam, Khasab Bay was of particular interest to the British owing to its deep anchorage. Pelly even recommended relocating the Gulf Naval Squadron’s base to Khasab Bay, along with the entire British Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. . Further, in 1866, he wrote to the Superintendent of the telegraph station informing him that he would be coming to Musandam to hear a complaint against the Wali of Khasab (Mss Eur F126/43, f. 51v). Such an intervention was indicative of Britain’s reach into and dominance over the Trucial Coast A name used by Britain from the nineteenth century to 1971 to refer to the present-day United Arab Emirates. and Oman.

British Intelligence Gathering

In November 1906, British military intelligence officer Lieutenant-Colonel Wilfrid Malleson passed by Musandam Island on his way up the Gulf to assess the Ottoman defences. The report he produced no doubt proved useful to British military planners during the Mesopotamian Campaign when an expeditionary force penetrated the Ottoman Empire via Basra.

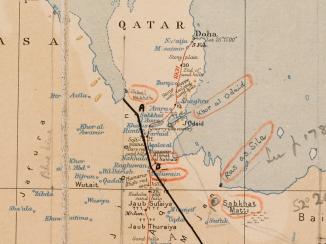

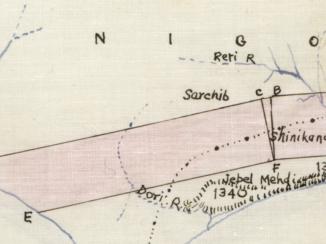

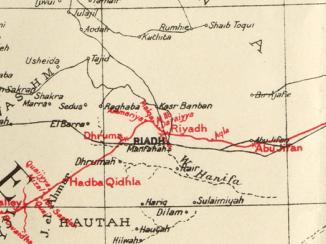

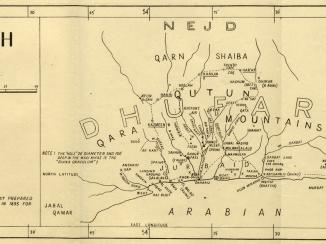

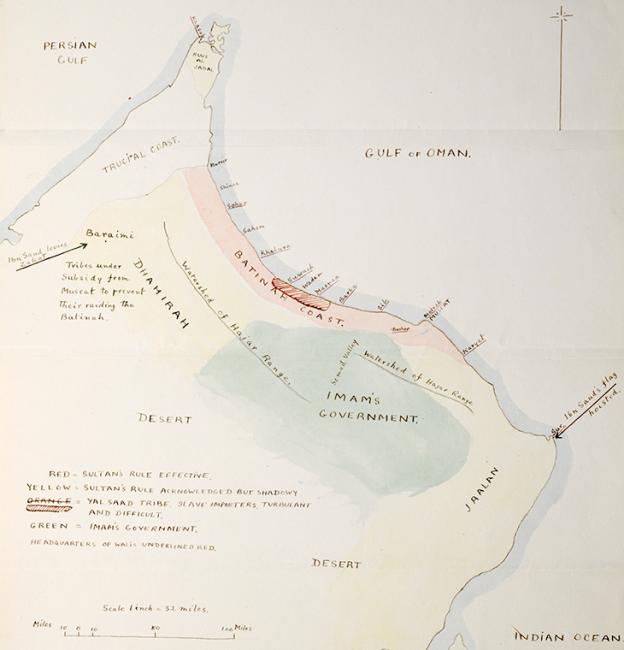

The advent of European oil exploration in the Arabian Peninsula during the 1920s also saw a marked shift in the focus of intelligence gathering. Malleson’s report concentrates on the outline of the coast and the military implications for attack or defence. By contrast, two decades later there was more interest in the allegiances of different tribes, as the demarcation of territorial sovereignty could have implications for the signing and development of oil concessions as well as other fiscal matters. Bertram Thomas (Financial Advisor to Sultan Taymur bin Faysal from 1924) conducted reconnaissance in Musandam in 1926. His objectives included identifying tribal allegiances in order to assist in resolving disputes and collecting taxes. He produced a hand-drawn map of Musandam shaded with different colours to indicate apparent allegiances both to various Trucial Shaikhs and to the Sultan of Muscat. Thomas also collated notes on the Shiḥūḥ tribe, which was based in Musandam and resistant to the authority of Muscat. In their correspondence at this time, British officials, including Thomas, are disparaging of the Shiḥūḥ, categorizing them as ‘rude, suspicious and wild’ (IOR/R/15/6/246, f. 8r). In a 1928 sketch map, Major George Patterson Murphy, the Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. in Muscat, classifies the Sultan’s rule in Musandam as ‘acknowledged but shadowy’.

Resistance within the Peninsula

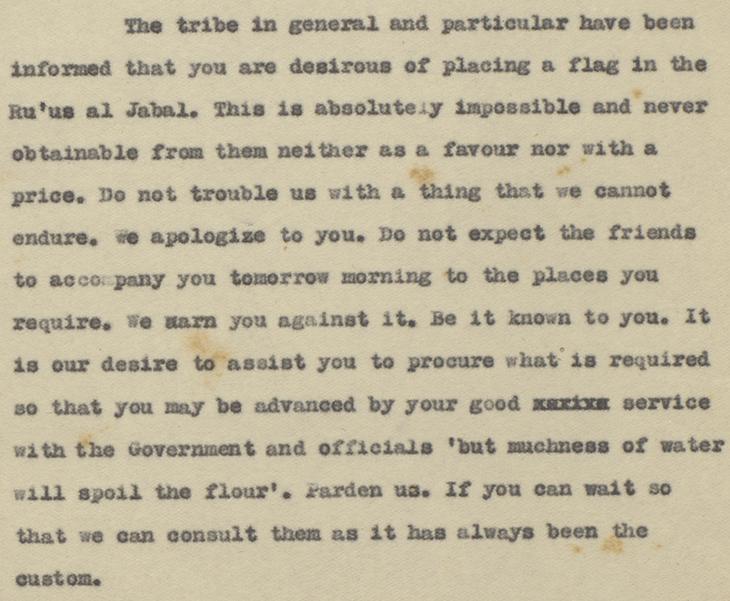

In the last days of Sultan Taymur bin Faysal’s rule, his Council of Ministers approved a British attempt to send the survey ship HMS Ormonde from Aden, but this met with resistance from the Shaikhs of Khasab, Dibba, Bukha, and Kumzar. Seeking to subdue these Shaikhs, the Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. at Bushire ordered HMS Lupin to bombard Khasab. During the course of this bombardment, the Shaikh of Khasab, Hassan bin Muhammad, wrote to representatives on board the Ormonde, explaining that Britain and Muscat were seen to be ‘desirous of planting a flag in the Ru’us al Jabal [Musandam Peninsula]’ and that this was ‘absolutely impossible and never obtainable […] neither as a favour nor with a price.’ Similarly, the Shaikh of Dibba, Salah bin Muhammad, wrote to the Ormonde warning that ‘we will not give our places to any body […] you are not a king over us […] and we wish you to postpone the interference’ (IOR/R/15/6/41, f. 94r).

The inhabitants of Musandam resisted the intrusion and interference of both Muscat and Britain in their affairs, but this resulted in the Shaikh of Khasab’s imprisonment in Muscat for eighteen months from May 1930. Britain continued to enforce the authority of the Al Bu Sa‘id Sultanate in Musandam, even into the 1970s. In 1971, as Britain formally withdrew from the Gulf, Operation Intradon parachuted British troops into Musandam to counter possible Arab nationalist or radical left-wing forces. By this time, the Sultanate of Muscat and Oman along with the Musandam Peninsula had morphed completely in British eyes from a point of strategic interest on the route to British India into a vital component of “Gulf security” and the transit of oil tankers.