Overview

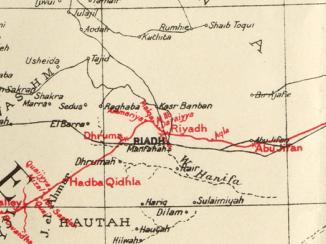

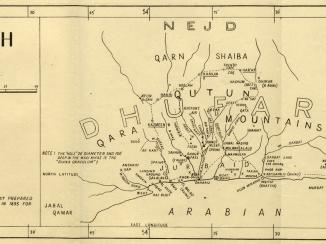

Frankincense has an allure that never ceases to capture the imagination but it is little-known that the major centre of production is the Sultanate of Oman’s Dhofar province, which is the only part of the Arabian peninsula to directly catch the Indian Ocean monsoon.

In Oman, Dhofar province continues to host the major centres for production of the rare substance. Today those sites, as well as the historic port of Al-Bilad, are inscribed as UNESCO World Heritage Sites, because frankincense has been traded in the region since ancient times.

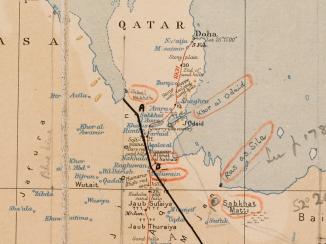

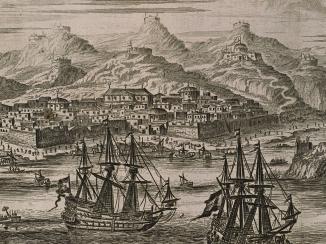

While the historic port of Al Bilad had already begun to decline in the twelfth century, by the fifteenth century both Al-Bilad and the other main centre of export, Khor Rorī, were in ruins as a result of the changed trading patterns caused by the Portuguese and other European nations’ trading in the region.

Harvest and Distribution

Frankincense was traditionally harvested by making a shallow cut into the bark of the Boswellia sacra tree. The sap of the tree would ooze out and begin to harden into a resinous substance, which was then collected and stored in caves to dry out. Once dry, it could be sent to Khor Rorī and Al-Bilad for export to India or to Egypt and Palestine by camel in a caravan that would traverse the overland trail.

But what is it exactly about Dhofar which leads to the production of the highest quality frankincense? ‘A note on the Dhofar province, southern Arabia’, prepared in 1943 by a British official named G. N. Jackson, describes how the topography of Dhofar and distribution of moisture affected the quality of the frankincense resin.

According to Jackson, the frankincense trees growing in the wadis on the north side of the mountains produced the best resin for incense due to the ‘dryness of the air’.

As these reports explain, it is the unique geographical conditions which mean that Dhofari frankincense continues to be the most prized of all, and still commands high prices on the global market.

The Frankincense Trail

From its starting point in Dhofar, the ancient Frankincense Trail, which passed through Yemen and Saudi Arabia to Jerusalem, has created great wealth over many centuries.

Around the first century BC much of the trade was controlled by the northern Arabian tribe, the Nabateans, from their capital Petra in modern-day Jordan. They allowed safe passage to caravans of camels carrying the incense but levied a payment for this protection.

Tensions as a Result of Trade

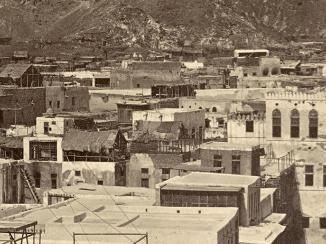

In fact, wealth generated in Dhofar as a result of Frankincense production and distribution has played a role in more recent political tensions as well as outright conflict between the population of the region and the Sultans in Muscat.

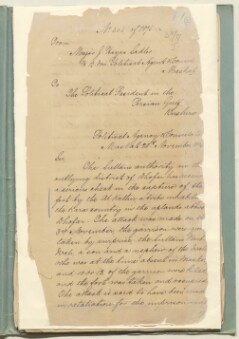

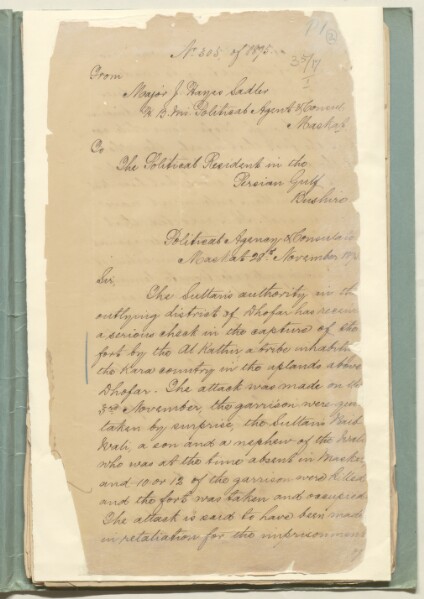

In the late nineteenth century, the ancient practice of facilitating and controlling the trade of Frankincense by means of a levy was still in place. A report compiled by Major J. Hayes Sadler from 1895 describes how a dispute with the Sultan of Muscat in Dhofar that centred on such a practice led to a rebellion against the Sultan’s rule in the region.

On the 3 November of that year the al Kathir tribe from the uplands captured the Sultan’s fort in Salalah. The garrison was taken by surprise and ten or twelve men were killed. Hayes Sadler noted that ‘The attack was in retaliation for the imprisonment of a man of the al Kathir tribe who was accused of attempting to evade the payment of the Sultan’s dues on a large consignment of frankincense which passed through Dhofar some while ago’.

When the population of Dhofar almost unanimously sided with the al Kathir, Haye Sadler drew the conclusion that the discontent with the Sultan’s rule must be widespread. He attributed it to the ‘oppressive and extortionate demands’ of the Sultan’s wali (governor) Sulaimin bin Suwailim.

As Oman increasingly came into the British sphere of influence in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries British officials travelled to Dhofar to prepare such reports on its economy, geography and society. Thus, in 1907, Major W. G. Grey, the Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. in Muscat, visited Dhofar and compiled a report for the Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. in which he commented on the continuing frankincense trade:

Fishing is carried on by the poorer classes and the little export trade there is, is in Frankincense which is brought down from the Samhan range and exported chiefly to Bombay in dhows which come from thence with rice, cloth etc. for sale of exchange.

The British produced such records on the continuing – if diminished – production of frankincense because they were interested in the political and economic climate of trade in the region. Any revenues, from whatever source, accrued by the Sultan of Muscat would increase his financial viability and, as the Sultan had agreed to take British advice on all ‘important matters’, this would in turn help buttress and maintain British influence in the region.